Feb. 2nd, 2013

A lot to cover this week – the monthly labor report and the Dow Industrial Average breaks the psychological mark of 14,000. Let’s cover the stock market rise because that will give us some context for the labor report.

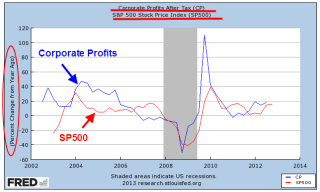

The stock market rises and falls on the prospect for the rise and fall in corporate profits. For the past year, profits have been healthy, increasing year over year by 15-20%.

The stock market is a compilation of attempts to anticipate these profit changes by six months or so. Sometimes it guesses wrong, sometimes it guesses right but the market loosely follows the trend in profits.

As a percent of GDP, corporate profits have reached a record high and this growing share of the economy is largely responsible for the doubling of the SP500 in the past three years.

There can be too much of a good thing and this may be it. An economy becomes unstable as one segment of the economy accumulates a greater share of the pie.

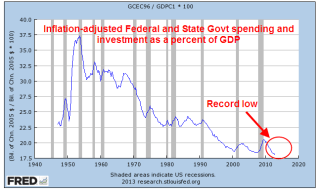

Facts are the nemesis of partisan hacks who simply disregard any information that does not fit with their model of how the universe works. Data on government spending and investment contradict those who complain that government has too much of a share of the economy; it is now at historic lows.

This includes government at all levels: federal, state and local. Reductions in government spending continue to act as a drag on both GDP and employment growth. What gives some people the sense that government spending is a larger percentage of the economy are transfer payments, like Social Security. Neither the calculation of GDP or government spending includes these transfer payments, so the percent of government spending in relation to GDP as shown in the chart above is a truer picture of government’s role in the economy.

Speaking of GDP – this past week came the first estimate of GDP growth for the fourth quarter of 2012. The headline number was negative growth of 1/10th of a percent on an annualized basis.

Two quarters of negative growth usually mark the beginning of a recession. Concern over this negative growth led to small losses in the stock market at mid-week as investors grew concerned about the January labor report, which was released Friday. The negative growth was largely due to a severe reduction in defense spending and exports. As a whole, the private economy grew at an annualized rate of 3.6%, a strength that helped moderate any market declines in mid week.

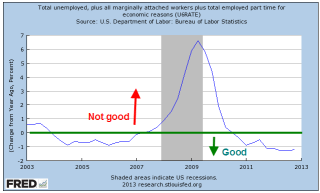

When the Bureau of Labor Statistics released their monthly labor report this past Friday, the headline job increase of 157,000+ and an unemployment rate stuck at 7.9% did not calm investors’ fears. The year over year percent change in unemployment is still in positive territory.

The numbers of long term unemployed as a percent of total unemployment ticked down but remains stubbornly high at about 38% (seasonally adjusted)

What prompted Friday’s relief rally in the market were the revisions in the previous months’ employment gains. As more data comes in, the BLS revises previous months’ estimates. This month also included end of the year population control adjustments.

November’s gains were revised from +161,000 to +247,000; December’s gains were raised from +155,000 to +196,000. For all of 2012, the revisions added up to additional job gains of 336,000, raising average monthly job gains for 2012 to 181,000 – near the benchmark of 200,000 needed to make a dent in the unemployment rate. Previous decreases in the unemployment rate have been largely the result of too many people giving up looking for work and simply not being counted as unemployed.

Overall, the labor report put the kibosh on any fears of recession and the stock market responded with a rally of just over 1%. Construction jobs continued their recent gains but employment levels are one million jobs fewer than the post-recession lows of 2003 and two million jobs less than the 2006 peak of the housing bubble.

The core work force aged 25-54 continues to struggle along.

The older work force has garnered much of the gains in the past year but this month was flat.

The larger group of workers counted as unemployed or underemployed, what is called the U-6 Rate, remained unchanged as did the year over year percent change.

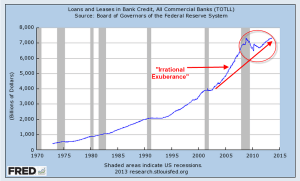

As the stock market continues to rise, retail investors have reversed course and have started to put more money into the stock market. Sluggish but steady GDP and employment growth has prompted the Federal Reserve to continue its program of buying bonds every month, which tends to push up stock market values. The Fed can continue this program as long as the sluggish pace keeps inflation in check and below the Fed’s target rate of 2.5%.

In the short run, it is a good idea to follow the maxim of “Don’t Fight the Fed.” What is of some concern is the long term picture. Below is a 30 year chart of the SP500 index, marked in 10 year periods with two trend lines based on the first decade, one trend line (with the arrow) a bit more positive than the other.

The market has changed in the past two decades. The bottoms in 2002, 2003, 2010, 2011 were simply a return to trend, a return to sanity. The downturn of late 2008 – early 2009 was the only downturn that broke below trend; truly, an overcorrection. Among the changes of the past two decades is a Federal Reserve that, some say, has helped drive these erratic asset bubbles by making aggessive interest rate moves, then keeping interest rates at low levels for a prolonged period of time. Whether and how much the Fed’s interest rate policies contribute to stock market valuations is a matter of much vigorous discussion. Whatever the causes are, it is important to recognize that over two decades the market has shifted into a jagged, cyclic investment. The long term investor who has a ten year time frame before they might need some of the money invested in the stock market can be reasonably certain that they will be able to get most of their money back if not make a healthy profit. For those with a shorter time horizon like five years, they will need to monitor the financial and economic markets a bit more closely or hire someone to do it for them. This is especially true when one is buying at current market levels which are above trend.