June 29, 2014

This week I’ll review some of this week’s headlines in GDP, personal income, spending and debt, housing and unemployment. Then I’ll take a look at some trends in education, including state and local spending.

**************************

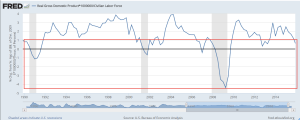

Gross Domestic Product First Quarter 2014

The headline this week was the third and final estimate of GDP growth in the first quarter, revised downward from -1% to -2.9%. This headline number is the quarterly growth rate, or the growth rate over the preceding quarter. A year over year comparison, matching 2014 first quarter GDP with 2013 first quarter GDP, shows an annual real growth rate of 1.5%, below the 2.5 to 3.0% growth of the past fifty years. The largest contributor to the sluggish GDP growth was an almost 5% drop in defense spending. Simon Kuznets, the economist who developed the GDP concept, did not include defense spending in the GDP calculation.

Contributing to the quarterly drop was the 1.7% decline in inventories. Businesses had built up inventories a bit much in the latter half of 2013 in anticipation of sales growth only to see those expectations dashed by the severe winter weather. Final Sales of Domestic Product is a way of calculating current GDP growth and does not include changes in inventory. Let’s look at a graph of the annual growth in Real (Inflation-Adjusted) GDP and Real Final Sales of Domestic Product to see the differences in the two series.

Note that Real GDP growth (dark red line) leads Final Sales (blue line) as businesses build and reduce their inventory levels in anticipation of future demand and in reaction to current and past demand.

The Big Pic: if we look at these two series since WW2, we see that ALL recessions, except one, are marked by a year over year percent decline in real GDP. The 2001 recession was the exception.

Secondly, note that in half of the recessions, y-o-y growth in Final Sales, the blue line in the graph, does not dip below zero. We can identify two trends to recession: 1) businesses are too optimistic and overbuild inventories in anticipation of demand, then correct to the downside, causing a reduction in employment and a lagging reduction in consumer spending; 2) consumers are too optimistic and take on too much debt – selling an inventory of future earnings to creditors, so to speak – then correct to the downside and reduce their consumption, causing businesses to cut back their growth plans. In case #1, a decrease in consumer spending follows the cutbacks by businesses. In case #2, businesses cut back following a downturn in consumer spending.

In this past quarter, employment was rising as businesses cut back inventory growth, indicating more of a rebalancing of resources by businesses rather than a correction. Consumer spending may have weakened during the first quarter but, importantly, did not decline. We have two hunting dogs and neither is pointing at a downturn.

For a succinct description of the various components of GDP, check out this article written for about.com by Kimberly Amadeo. Probably written in the first quarter of 2014, her concerns about the inventory buildup in 2013 were proved accurate.

**************************

Income and Spending

Personal Income rose almost 5% on an annualized basis in May but consumer spending rose at only half that pace, 2.4%. The spending growth is only slightly more than the 1.8% inflation rate calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, revealing that consumers are still cautious.

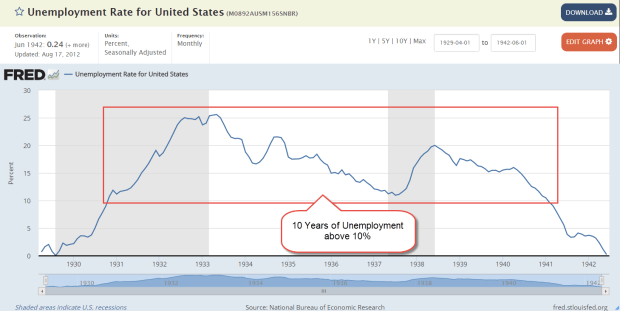

I heard recently a good example of how data can be presented out of context, leading a listener or reader to come to a wrong conclusion. Data point: the dollar value of consumer loans outstanding has risen 45% since the start of the recession in late 2007. Consumer loans do not include mortgages or most student loan debt. If I were selling a book, physical gold, or a variable annuity with a minimum return guarantee, I could say:

My friends, this shows that many consumers have not learned any lessons from the recession. They are living beyond their means, running up debts that they will not be able to pay. Soon, very soon, people will start defaulting on their debts and the economy will collapse. This country will suffer a depression that will make the 1930s depression look tame. Now is the time to protect yourself and your loved ones before the coming crash.

Data is little more than an opportunity to spread one’s political message. Data should never lead us to reconsider our message, our point of view. If I were penning a politically liberal message, I could write:

The families in our country are desperate. Without enough income to satisfy their basic needs, they are forced to borrow, falling ever deeper into debt while the 1% get richer. We need policies that will help families, not the financial fat cats on Wall Street. We need a tax structure that will ensure that the 1% pay their fair share and not have the burden fall on the shoulders of most of the working Americans in this country.

Selling a political persuasion and selling a car brand often employ similar techniques. Data should never lead us to question our loyalty to the brand. If I were crafting a conservative message, I could write:

The misuse of credit indicates an immaturity fostered by cradle to grave social programs, which are eroding the very character of the American people, who come to rely less on their own resources and more on some agency in Washington to help them out. People steadily lose their sense of personal responsibility, becoming more like children than self-reliant adults.

However, the facts behind the data point lead us to a different story. In the spring of 2010, consumer loans spiked, rising $382 billion in just two months.

That surge represents more than a $1000 in additional debt per person. Consumers did not suddenly go crazy. Banks did not open their bank vaults in a spirit of generosity. Instead, banks implemented accounting rules FAS 166 and 167 that required them to show certain assets and liabilities on their books. $322 billion of the $382 billion increase in consumer loans during those two months in 2010 was the accounting change. If we subtract that accounting change from the current total, we find that real consumer loan debt increased only 5.5% in 6-1/2 years. And that is the real story. Never in the history of this series since WW2 have consumers restrained their borrowing habits as much as we have since December 2007. We had to. In the eight years before the financial crisis in 2008, real consumer debt rose 33%, an unsustainable pace.

About two years ago, loan balances stopped declining and since then consumers have added $80 billion, much of it to finance car purchases. $25 billion of that $80 billion increase has come only since the beginning of this year. On a per capita, inflation adjusted basis, consumer loan balances are still rather flat.

**************************

Housing

New home sales in May were up almost 20% over April’s total, and over 6% on an annual basis. Existing homes rose 5% above April’s pace but are down 5% on an annual basis. Each year we hope that housing will finally contribute something to economic growth. Like Cubs fans, we can hope that maybe this year….

**************************

Unemployment Claims

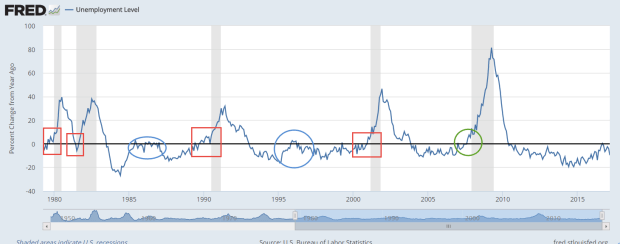

New unemployment claims continue to drift downward and the 4 week moving average is just below 315,000. Our attention spans are rather short so it is important to keep in mind that the current level of claims is the same as what is was last September.

It has taken this economy six months to recover from the upward spike in claims last October. The patient is recovering but still not healthy.

**************************

Minimum Wage

The number of workers directly affected by changes in the minimum wage are small. We sympathize with those minimum wage workers who try to support a family. The Good Samaritan impulse in many of us prompts us to say hey, come on, give these people a break and raise the minimum wage. What we may forget are the implications of any minimum wage increase. Older readers, stretch your imagination and remember those years gone by when you were younger. Workers in their early working years often see the minimum as a benchmark for comparison. The much larger pool of younger workers who make above minimum wage may push for higher wages in response to increases in the minimum wage.

Fifty years ago, Congress could have made the minimum wage rise with inflation, ensuring that workers in low paid jobs would get at least a subsistence wage and that increases would be incremental. Of course, there are some good arguments against any nationally set minimum wage. $10 in Los Angeles buys far less than $10 in Grand Junction, Colorado. Ikea recently announced that they will begin paying a minimum wage that is based on the livable wage in each area using the MIT living wage calculator . Several cities have enacted minimum wage increases that will be phased in over several years but none that I know of are indexed to inflation as the MIT model does.

Congress could enact legislation that respects the differences in living costs across the nation. For too long, Congress has chosen to use the minimum wage as a political football. Social Security payments are indexed to inflation because older people put pressure on politicians to stop the nonsense. There are not enough minimum wage workers to exert a similar amount of coordinated pressure on the folks in Washington so workers must rely on the fairness instinct of the larger pool of voters if any national legislation will be passed.

**********************

Education

Demos, a liberal think tank, recently published a report recounting the impact of rising tuition costs on students and families. Student debt has almost quadrupled from 2004 – 2012. Wow, I thought. State spending per student has declined 27%. More wows. How much has enrollment increased, I wondered? Hmmm, not mentioned in the report. Why not?

The National Center for Education Statistics, a division of the Dept. of Education, reports that full time college enrollment increased a whopping 38% in the decade from 2001-2011. Part-time enrollment increased 23% during that time. Together, they average a 32% increase in enrollment. Again, wow! Ok, I thought, the states have been overwhelmed with the increase in enrollment, declining revenues because of the recession, etc. Well, that’s part of the story. Spending on education, including K-12, is at the same levels as it was a decade ago.

From 2002-2012, states have increased their spending on higher ed by 42%. Some argue that the Federal government should step up and contribute more. In 2010, total Federal spending on education at all levels was less than 1% ($8.5B out of $879B). Others argue that the heavily subsidized educational system is bloated and inefficient. As much cultural as they are educational institutions, colleges and universities have never been examples of efficiency. Old buildings on college campuses that are expensive to heat and cool are largely empty at 4 P.M. Legacy pension agreements, generously agreed to in earlier decades, further strain state budgets. We may need to rethink how we can deliver a quality education but these are particularly thorny issues which ignite passions in state and local budget negotations.

Although state and local governments have increased spending on higher ed by 42% in the decade from 2002-2012, the base year used to calculate that percentage increase was particularly low, coming after 9-11 and the implosion of the dot-com boom. Nor does it reflect the economic realities that students must get more education to compete for many jobs at the median level and above.

Let’s then go back to what was presumably a good year, 2000, the height of the dot-com boom. State coffers were full. In 2000, state and local governments spent 5.14% of GDP (Source). By 2010, that share had grown to 5.82% of GDP (Source). That represents a 13% gain in resources devoted to education. But that is barely above population growth, without accounting for the rush of enrollment in higher education during the decade.

Let’s take a broader view of educational spending, comparing the total of all spending on education, including K-12, to all the revenue that Federal, state and local governments bring in. This includes social security taxes, property taxes, sales taxes, etc. As a percent of all receipts, spending on education has declined from 30% to under 18%.

Many on the political left paint conservatives as being either against education or not supportive of education. Census data shows that Republican dominated state legislatures, in general, devote more of their budget to education than Democratic legislatures. W. Virginia, Mississippi, Michigan, S. Carolina, Alabama and Arkansas devote more than 7% of GDP to education, according to U.S. Census data compiled by U.S.GovernmentSpending.com. Only two states with predominantly Democrat legislatures, Vermont and New Mexico, join the plus-7% club (Wikipedia Party Strength for party control of state legislatures).

In the early part of the twentieth century, a high school education was higher education. In the early part of this century, college may be the new high school, a minimum requirement for a job applicant seeking a mid level career. What are our priorities? In any discussion of priorities, the subject of taxes arises like Godzilla out of the watery depths. People scramble in terror as Taxzilla devours the city. Older people on fixed incomes and wealthy house owners resist property tax increases. Just about everyone resists sales tax increases. Proposals to raise income taxes are difficult to incorporate in a campaign strategy for state and local politicians running for election.

Let’s disregard for a moment the ideological argument over Federal funding or control of education. Let’s ask ourselves one question: does this declining level of total revenues reflect our priorities or acknowledge the geopolitical realities of today’s economy?

***********************

Takeaways

Reductions in defense spending, inventory reductions and a severe winter that curtailed consumer spending accounts for much of the sluggishness in first quarter GDP growth.

A surge in new home sales is a sign of both rising incomes and greater confidence in the future.

Consumer spending growth is about half of healthy income gains.

Spending on education has grown a bit more than population growth and is not keeping up with surging enrollment in higher education.