October 5, 2014

On Monday George and Mabel flew to Portland, Oregon so Mabel could attend a teacher conference in Eugene on the development of strategies and practices for online learning. “How’d you get invited? You’re retired,” George had asked a few months earlier. Mabel had spent many years both as a teacher and high school principal.

“The conference is focused on post-secondary education, but Lorraine thought I would be interested and wangled me a spot.” Her friend Lorraine was a department chair at a local community college. “I might be able to give her some perspective from the high school level as these kids make the transition to college courses.”

They had to get up early to make the morning flight. Retired people should only get up this early when they are having a colonoscopy, George thought. After the conference, they planned to spend a few days on the Oregon coast, which they were both looking forward to. They sat in the Denver airline terminal awaiting the boarding call. George couldn’t understand most of what they said. Millions of dollars to build an airport and the contractors seemed to have bought the cheapest speakers through somebody’s Uncle Harry who knows a guy who’s got a connection with some exporter in Malaysia. Airline service had become little more than a subway in the sky. In fact, the speakers sounded just as bad as the ones used in New York subway cars. “Gate 23, now pre-boarding …” came out of the speakers as “Ateleeteehoweeornayhinienegetcrispbeergoremekeens.” Passengers, please get in the metal tube, sit down and be quiet. The metal tube will go up in the air and deposit you at your destination. Transportation for the masses. The future has turned out slightly different than the one imagined at the New York World’s Fair in 1964.

In Portland they rented a car and drove down to Eugene. Settling down in their hotel room, George was pleasantly surprised to find they had good wi-fi reception. The market had been up but had closed below Friday’s close, indicating that there was still more negative sentiment to come. Personal income in August had gained 4.3% above the level of August 2013.

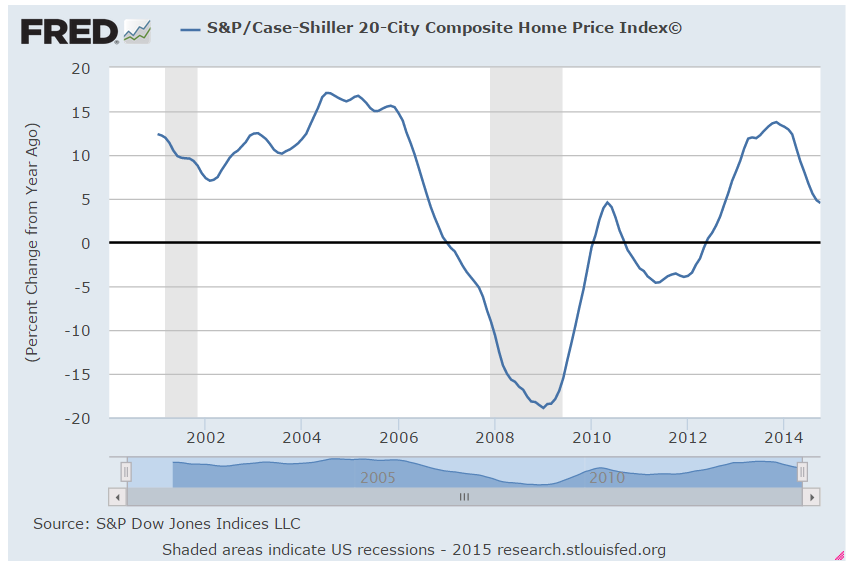

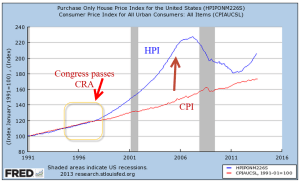

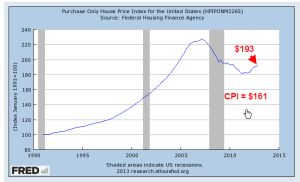

That bit of good news was offset somewhat by a report from the National Assn. of Realtors that year-over-year pending home sales were down a little bit more than 2% in August. This confirmed last week’s housing reports and made it unlikely that tomorrow’s Case-Shiller report on home sales would have any positive surprises.

Tuesday morning, George slept in while Mabel got up early to go to the nearby conference at the University of Oregon. He missed the free breakfast at the hotel but the woman at the reception desk pointed him to a nearby coffee shop that served egg croissants and a good cup of coffee. The sun broke out on the short walk to the coffee shop, brightening George’s mood. Despite the mid-morning hour, a number of people sat in the coffee shop working on their laptops. West coast time was three hours behind New York so half of the day’s trading had occurred before many Oregonians had started work.

The Case-Shiller home index showed that home prices in 20 metropolitan areas had declined for the third month in a row. Year over year gains were still positive at 6.7% but the pace of growth was slowing. Last Friday’s Consumer Confidence survey from the U. of Michigan had been positive and rising. A separate Confidence survey by the Conference Board was positive but showed a declining sentiment on worries about employment and income.

In the afternoon, he drove near the campus to meet Mabel. The campus was an artist’s rendition of what a college was supposed to look like. Shade trees dotted the grounds between the grand buildings of gray stone. Lawns and bushes were clipped but didn’t look overly manicured. The concrete walkways that led from one building to another were well maintained but showed the typical wear of traffic and a wet climate. The ghosts of mankind’s great minds and talents would feel comfortable on these grounds and in these halls.

Mabel introduced George to several colleagues attending the conference. Most attendees were teachers and administrators in their forties and fifties. For 300 years, teachers and students had gathered in a classroom in what was called face-to-face education. Students prepared for class at home at various times outside of the classroom but the daily routine of classes centered the educational activity of the students. Online learning was a new phase in distance learning, attempting to blend the broader educational training of traditional colleges and universities with the asynchronous methods of the correspondence schools of the past century.

On Wednesday came further confirmation that the growth in housing sales and construction was slowing. Year-over-year construction spending had increased 5% but the growth had declined for 9 months. George thought this was a fairly normal cycle but the market reacted negatively, dropping more than 1% by the end of the day.

European Central Bank head Mario Draghi announced that they would continue to keep interest rates low to help spur the non-existent growth or decline in many European countries. The private payroll processor ADP reported job gains of 215,000, slightly above expectations. The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) showed a slight decline from the robust growth of the previous month but overall a very positive report.

Wednesday evening after the conference had concluded, George and Mabel had dinner at a restaurant with two women who had attended the conference. The conversation was lively, the food a bit pricey for the quality but George enjoyed the evening. For the past two days he had encountered many young people, reminding him of his college days decades before.

“I’ve decided I want to be 20 years old again, only not as dumb and inexperienced,” George quipped. He remembered sagely pronouncing that Fitzgerald’s novel, The Great Gatsby, was about social classes that no longer existed in America and was irrelevant. Somehow he had survived his own poor judgment. He did want to jump high in the air once again, twisting toward the basket and snapping a 3-point shot at the basketball net. The losses in physical vitality were offset by the gains in sagacity, George hoped.

On Thursday, George and Mabel woke up early (again! two times in one week!) to drive out from Eugene to the Oregon Coast. At the Oregon Dunes they walked through coastal rain forest, then dunes, then a less dense strip of rain forest, then beach and ocean. “I get smaller the more I walk,” he told Mabel. “What do you mean?” she asked. “We walk through places like this, they’re like landscapes, I guess you could call it, shaped by this wind around us, the ocean out there, and underneath our feet the earth is shifting about. It’s like we’re teeny tiny bacteria walking on the ridges of paint left by some artist’s brush.”

Mabel smiled, “Well put.” She paused. “With the physical classroom, students and teachers can have field trips out to the Oregon dunes. How do we take that and put it in an online environment?” she wondered. George glanced at her. “Someone has brought the conference to the beach, I think.” Later, they stopped off for a coffee in the old town of Florence before ending the day in Yachats where they stayed at the Overleaf Inn.

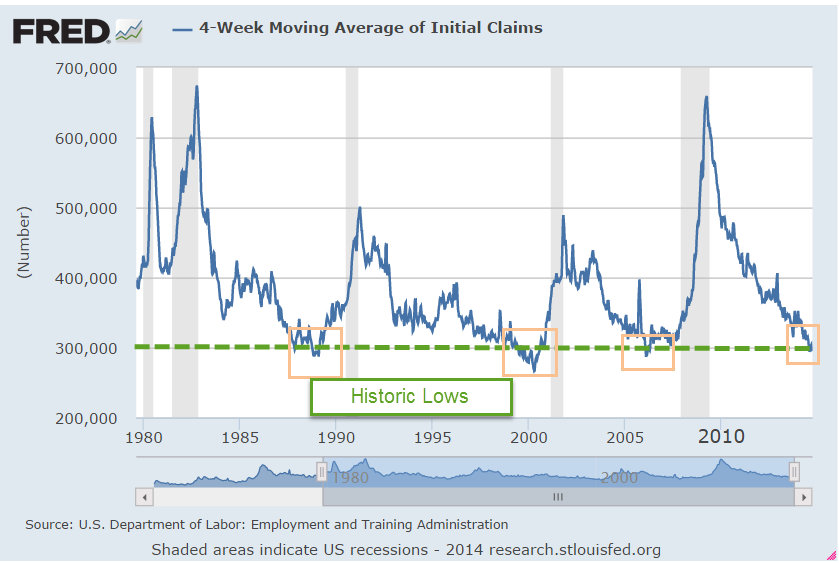

I could get used to this, George thought, checking the market news from his balcony while the last streaks of sunset and orange turned to purple and gray out over the ocean. The BLS reported that the 4-week average of new unemployment claims had fallen below 295,000.

Levels lower than this had occurred rarely – in early 2006, 2000 and the winter of 1987-88. Yet there was no dancing in the streets.

Instead, investors focused on the 10% drop in factory orders for August. Most of the decline was due to volatile aircraft orders, which had surged in July followed by an equal drop in August. The market remained flat.

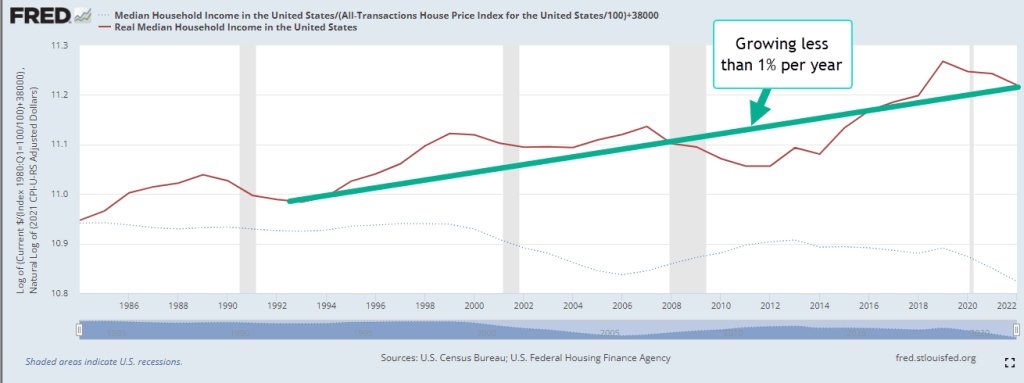

On Friday, George and Mabel walked several miles on the 804 trail, a sometimes dirt, sometimes asphalt path that ran for many miles along the Oregon cliffs. They ate at the Drift Inn that evening. Good food. “You think there’s much work for younger folks around here other than the tourist industry?” he asked Mabel. “I doubt it,” she replied. “We’ve seen a lot of twenty-somethings working at hotel reception desks, waiters, waitresses, the coffee shop in Florence. They can’t be making a lot of money. Still it is lovely here”, she mused. “Could be more sun, ya know?” George nodded. “We’re kinda spoiled in Colorado,” he said.

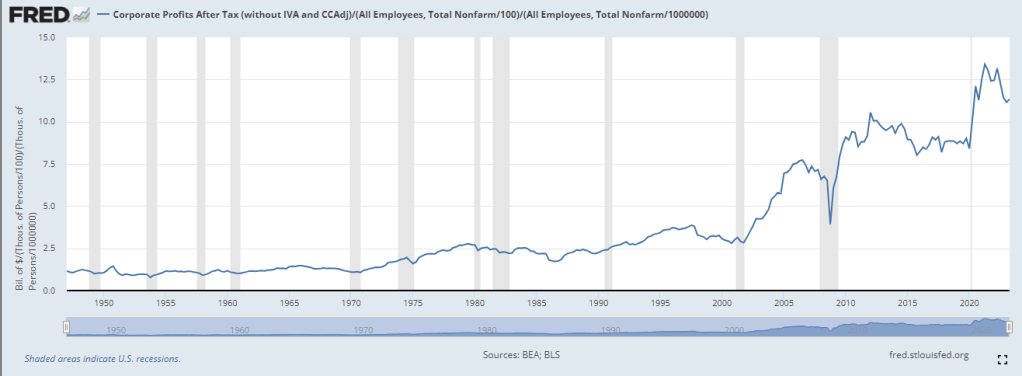

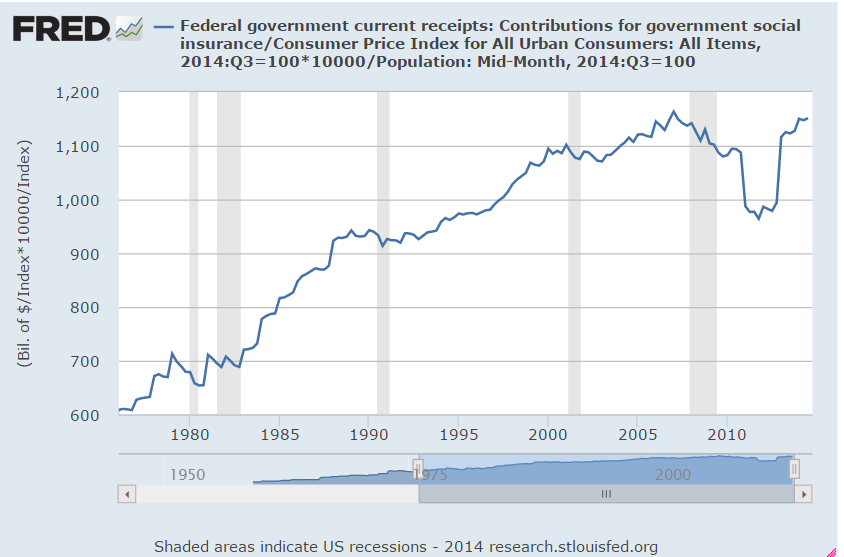

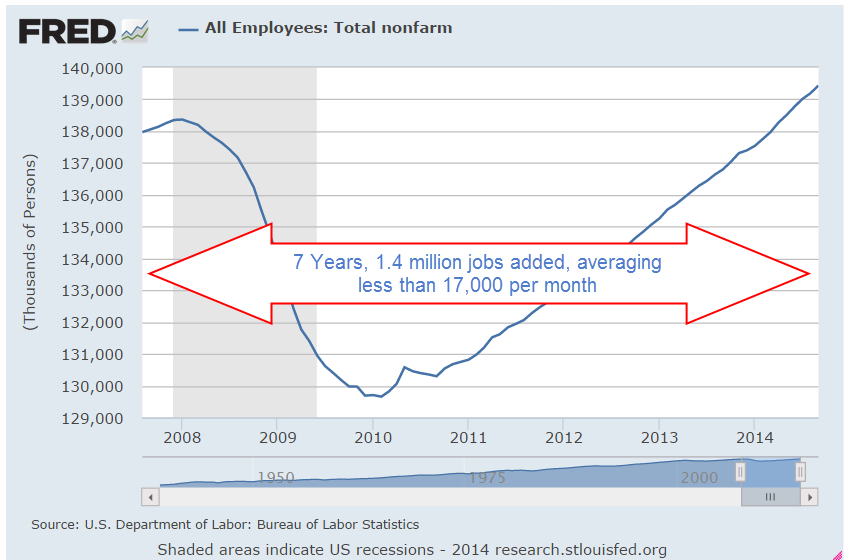

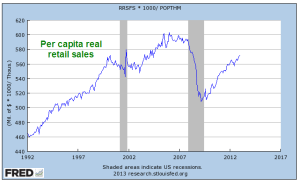

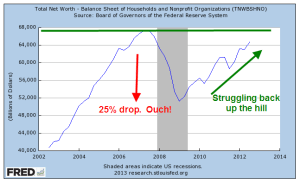

When they returned to their hotel room later that night, a stiff wind blew off the ocean, bringing with it a bit more chill than either of them had packed for on this trip. George checked the monthly employment data released that morning by the BLS. Job gains had surprised to the upside at almost 250K but the market had still closed below Wednesday’s opening price and was still below the 10-day average. He pulled up some FRED data to get a snapshot of the relative health of the labor force seven years after the start of the recession. The results were rather chilling – or maybe it was the dampness of the Oregon coast that he was unaccustomed to. In seven years the number of employed people had grown just 1% – not 1% annually but 1% total for the entire time.

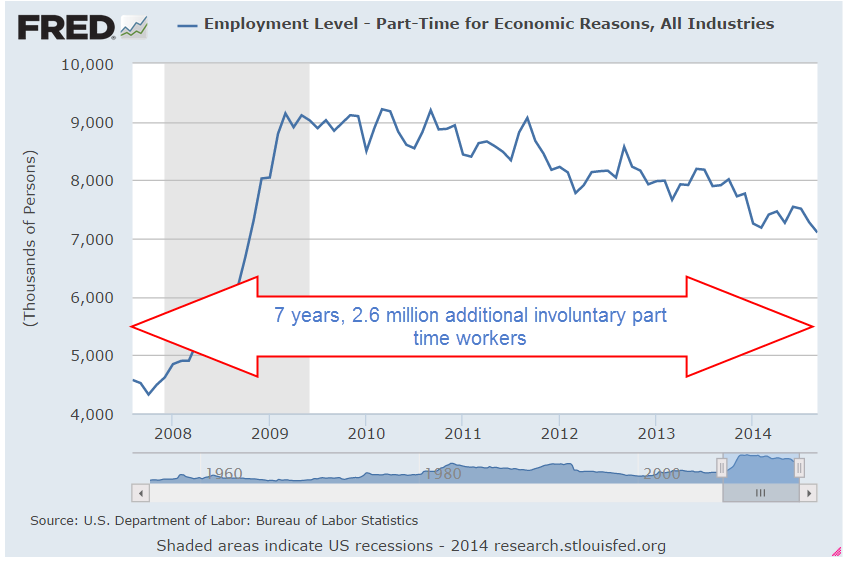

2.6 million more people were working part time because they could not find full time work. The number of underemployed had grown almost twice the 1.4 million new jobs created in seven years.

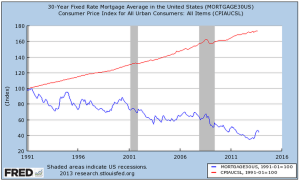

The unemployment rate had dropped below 6% in September but even that bit of positive news did not look so good when George pulled up the historical snapshot of unemployment since the recession began.

The rate had risen more than 1% in those seven years. Despite all the talk of recovery, the surge of stock prices from the lows of 2009 and the rise in home values, the labor market was still wounded.

“Why don’t you help me figure out where we’re going to stay tomorrow in Newport?”, Mabel asked. “One of my friends suggested the Elizabeth St. Inn.”

“Fine with me. I want to see the Aquarium if it’s open,” George replied. “Hey, check out the moon.” Then he put on his windbreaker, pulled a blanket off the bed and went to sit out on the balcony. Through the shifting clouds, moonlight shone softly on the water below. Mabel, taking a cue from her husband, tugged a blanket from the second bed, wrapped it around her and sat with him.