October 8th, 2017

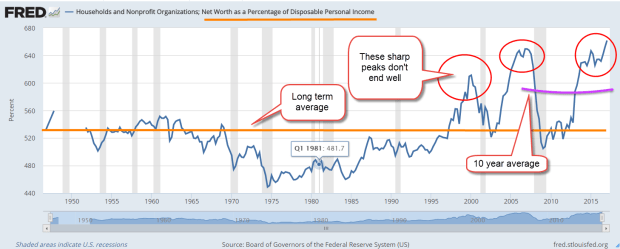

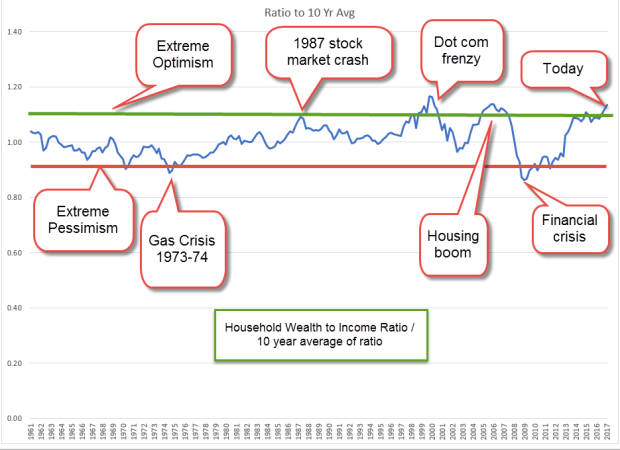

The Federal Reserve recently released their triennial survey of household income, debt and wealth. Rising asset values have lifted the fortunes of many, but younger families are struggling. I’ll show a reliable indicator of recessions as well as some trends peeking out behind the numbers. The incomes below are denoted in inflation adjusted 2016 dollars.

The good news is that lower income workers have recently seen some income gains, which the Federal Reserve attributes to the enactment of minimum wage laws in 19 states at the start of 2017. However, single parent families have struggled with income gains, as they have for three decades. The decade from the late 1990s to the financial crisis in 2008 lifted the incomes of single parents but they have struggled during the recovery. Median incomes for this group remain below the 2007 level.

That this group needed back-to-back historic asset bubbles in order to see some income gains shows just how vulnerable they are.

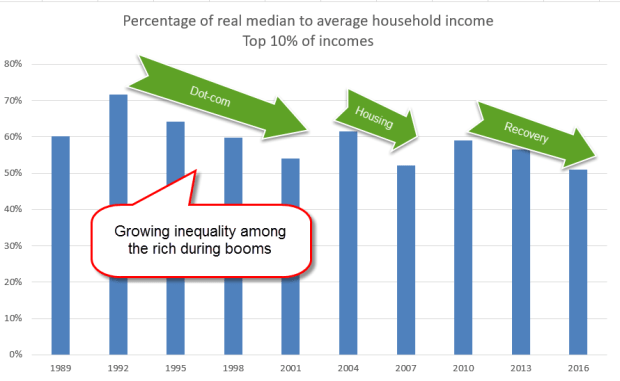

Much has been written about income inequality among households. During booms, there is a growing inequality even among those in the top 10% of incomes. The median in any data set is the halfway point in the numbers, and is usually less than the average of the numbers. If the numbers are evenly distributed the median is closer to the average and the percentage of median to average is high. When there are a lot of outliers that raise the average far above the median, as in home prices, the percentage is lower. During boom times there is growing inequality, even among the top 10% of incomes. (Data from survey)

The growth of inequality of income obeys a power law distribution. Think of a 1’x1’ square. The area is 1. Now double the sides to 2’x2’. The area quadruples to 4. Triple the sides to 3’x3’ and the area increases by a factor of 9. Let’s imagine that the area inside of a square is money. How fair is it that the 2’ square has four times the money that the 1’ square has? Politicians may pass tax and social insurance laws to take some of that money from the 2’ square and give it to the 1’ square. The redistribution of income and wealth can’t change the fundamental characteristics of a power law distribution. Despite the political rhetoric, solutions are bound to be temporary.

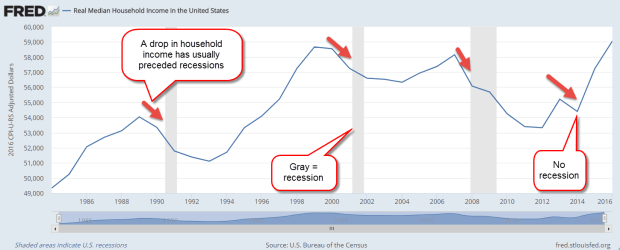

The income figures most cited are for households but this data has only been collected since the mid- 1980s. A fall in real median income usually precedes a recession except for the latest fall in 2014 when oil prices began to slide.

Let’s turn to the data for family household income that has been collected since the mid-1950s. What is the difference between a household and a family? By the Census Bureau definition, a family household consists of at least one person who is related to the householder by blood, marriage or adoption. A fall in family income has preceded every recession except a mild one in the 1960s. Family incomes rose very slightly just before that recession, due in part to a new optimism about the presidency of JFK and the promise of tax cuts.

Because this family income data is released annually at mid-year, this indicator is usually coincident with the start of a recession. However, it has proven quite reliable in marking the start of recessions.

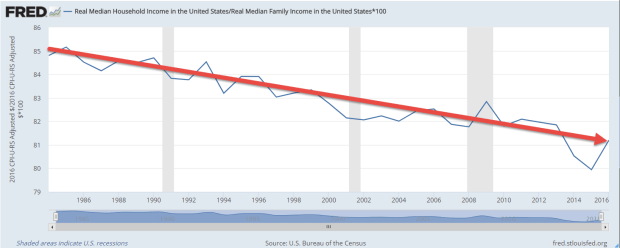

Non-family households are not related. This includes roommates or a childless couple living together but not married. Non-family households are generally younger and their income is less than the income of family households. Over the past three decades, the ratio of the incomes of all households to family households has declined.

Although younger people are experiencing slower growth in incomes, they will face increasing pressure to meet the demands of older generations expecting social insurance benefits like Social Security and Medicare. As the oldest Americans begin living in nursing homes in increasing numbers, they are expected to put an ever-growing burden on the Medicaid system (CMS report). It is the Medicaid system, not Medicare, which covers nursing home costs for seniors after they have depleted their resources. Although the number of nursing homes and certified nursing home beds have declined slightly in the past decade (CMS Report page 21), Medicaid spending still increased a whopping 10% in 2015 as enrollment expanded under Obamacare.

Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper has said that many states are expecting an increase in Medicaid spending on nursing home care as the first of the large Boomer generation turns 75 at the beginning of the next decade. CMS expects total health spending to increase 5.6% per year for the next decade. The last time we had nominal GDP growth that high was in 2006, at the peak of the housing boom.

The demands of both low income families and seniors on the Medicaid system will strain both federal and state budgets. The federal government can borrow money at will; states are constitutionally prevented from doing so.

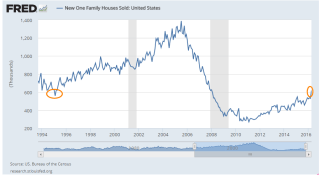

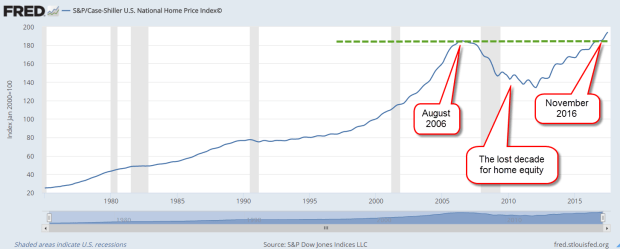

What will drive the high growth needed to sustain the promises of the future? New business starts are at an all-time low (CNN money). How did we get here? The financial crisis caused the failure of many small businesses, many of which are funded with a home equity loan by an entrepreneur. Home equity loans are down 33% from their peak in early 2009. At the end of last year, the Case-Shiller home price index finally regained the value it had in 2006. In the past decade there has been no home equity growth to tap into.

Imagine a couple in their late 30s or early 40s who bought a home 10 to 15 years ago. They may have only recently recovered the value of their home when they bought it. One or both may long to start a new venture but how likely are they to take a chance? In some of the bigger metro areas where home prices grew much stronger during the boom, prices are still below their peak ten years ago.

The market has priced in a tax cut package that will lower corporate taxes. Investors are expecting a third or more of those extra profits in dividends. Investors are expecting a compromise that will enable companies like Apple to “repatriate” their foreign profits to the U.S. and for that money to be used to buy back stock or pay down debt, both of which are positive for stocks. The IMF projects 3.6% global GDP growth in 2018. There’s good cause for optimism.

Investors have not priced in the long term effects of this year’s hurricanes, the volatility of commodities, the future risk of conflict with North Korea, the risk that the debt bubble in China, particularly in real estate, could escape the careful management by the Chinese government. Add in the several fault lines in household finances that the Federal Reserve survey reveals and there is good cause to season our optimism with caution.

Individual investors surveyed by AAII are cautiously optimistic, a healthy sign, but the sentiment of actual trading by both individuals and professionals shows extreme optimism, a negative sign. The VIX – a measure of volatility – just hit a 24-year low this past week, lower than the low readings of early 2007. Sure, there was some froth in the housing market, investors reasoned at that time, but nothing that was really a problem.

Then, oopsy-boopsy, and stocks began a two year slide. So, don’t run with joy, Roy. Don’t go for bust, Gus. Pocket your glee, Lee. Stick with your plan, Stan. There are at least “50 Ways To Leave Your Money,” and one of them is investing as though the future is predictable.