September 28, 2014

This past Monday George was out in the backyard when his wife Mabel came out on the back deck to announce that lunch was ready. From the deciduous vines that grew on the backyard fence George was pulling leaves that had turned an autumn shade of red.

“George, what are you doing?”

“I thought I would pull these leaves off before they fall. This way I won’t have to stoop so much a few weeks from now to pick them out of the rock garden. The leaves are getting in the pond and clogging up the filter.”

“Well, come on, dear. Lunch is ready. I heard on the radio a little while ago that the market is down. You know how I worry about that.”

“Oh, really?” George replied. “It was down last Friday. Did they give any reason?”

“Something about housing. I’m sure you’ll find out all about it while you are eating.”

Mabel had set a nice lunch plate of panini bread, cheese and vegetables. George was a tall man, a big boned man, prone to weight gain in retirement. Although George was fairly fit for his age, she worried about his health, particularly his heart, the male curse. Mabel made sure that they both ate sensible, healthy meals.

Mabel took her lunch into the living room, leaving George alone in the kitchen. He liked to check in on the stock market a few hours before the close to get a sense of the direction of the day’s action. She would have chosen to keep all their savings in CDs and savings accounts but the interest rates were so low that living expenses would slowly erode their principle.

“We’ll put just 25% of our money in the market,” George had told her. “I’ll watch it carefully and if anything like 2008 happens again, we can pull it out right away. I’ll know what the signs are.”

George had studied a book on technical indicators which were supposed to help a person understand the direction of the market. Despite her confidence in George’s ability and sensibility, Mabel still worried. The stock market had always seemed to her like gambling.

At the kitchen table, George turned on the computer while he chewed his carrots and celery. He had never been fond of vegetables but found that his likes and dislikes had mellowed with age. He liked that Mabel cared. The market helped distract him from the vegetables. He paged through the daily calendar at Bloomberg, then checked out the headlines at Yahoo Finance. Existing home sales in August had fallen more than 5% from the previous August but that was a tough comparison because 2013 had been a pretty strong year. Existing home sales were still above 5 million.

Before George had invested some of their savings in the stock market, he had bought several books on how to read financial statements but soon gave up when he realized that knowing the fundamentals of a company would not protect their savings in the case of another meltdown like the recent financial crisis. Patient though she might be, Mabel would be extremely upset with him if he lost half of his investment in the market.

He then turned to the study of technical indicators which analyzed the behavior of other buyers and sellers in the stock market. As an insurance adjuster, he had learned C programming back in the 1990s and found a charting program whose language was familiar to him. As a former adjuster for the insurance of commercial buildings, he was used to making judgments based on a complex interplay of many factors. He played with several indicators, found a few that seemed to be reliable, but got burned when the market melted down in the summer of 2011. He got out quickly but not quickly enough for he had lost more than 10% of his investment in the market. The market healed but at the time it seemed as though there might be a repeat of the 2008 crisis. Had George and Mabel been younger, George could have just ridden out the storm. Retirement had made him cautious and the 2011 downturn made George almost as leery of the market as Mabel.

Tuesday was a fine day in late September. Mabel put her crochet down and made the two of them some soup, with fruit, crackers and cheese. She took pride in the variety of food that she prepared. When she walked out on the deck to call George in for lunch, a startled crow took to flight. George was sitting on the edge of the deck where the crow had been.

“What are you doing, George?”

“I was teaching that little crow how to break open a peanut,” George replied. “I think they learn how to do stuff like that from their parents but I haven’t seen the flock in a few days and this guy was just wandering around the backyard looking for something to eat. When I gave him a peanut, he didn’t seem to know what to do with it. He’d pick it up in his beak, then drop it and stare at it. He pecked at it a few times but that only made the peanut skitter away. “

George held up a branch. “I carved a claw into the end of this branch and held down the peanut for him.” George held up half a peanut shell. “See, he got it figured out. He flew off when the door opened but I’ll betcha he’ll be back.”

“Well, come on in then. Lunch is ready. The market is down again. Something about housing again.”

“Hmmm,” George grunted and followed Mabel into the kitchen. “Hmmm, that soup smells good.”

“A little beef vegetable that I doctored up a bit,” Mabel said with a smile.

George gave her a little hug. “I sure like your doctoring.”

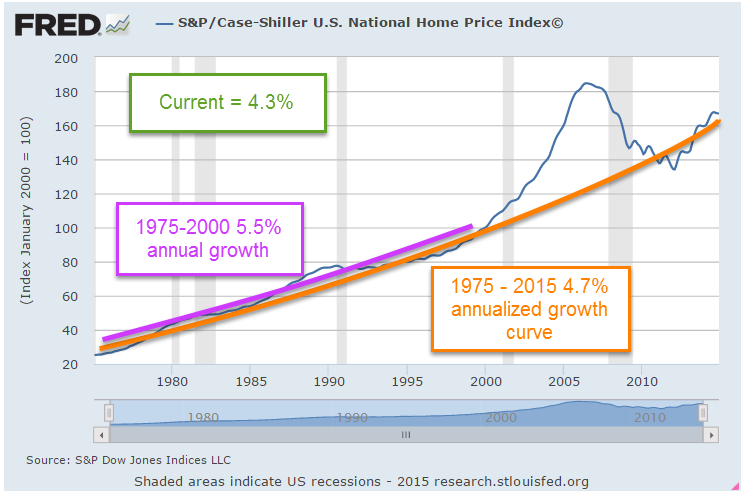

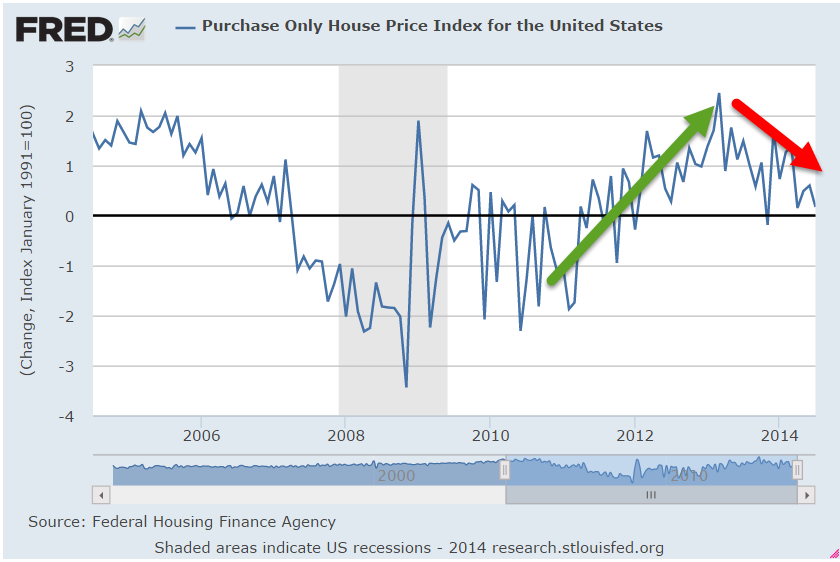

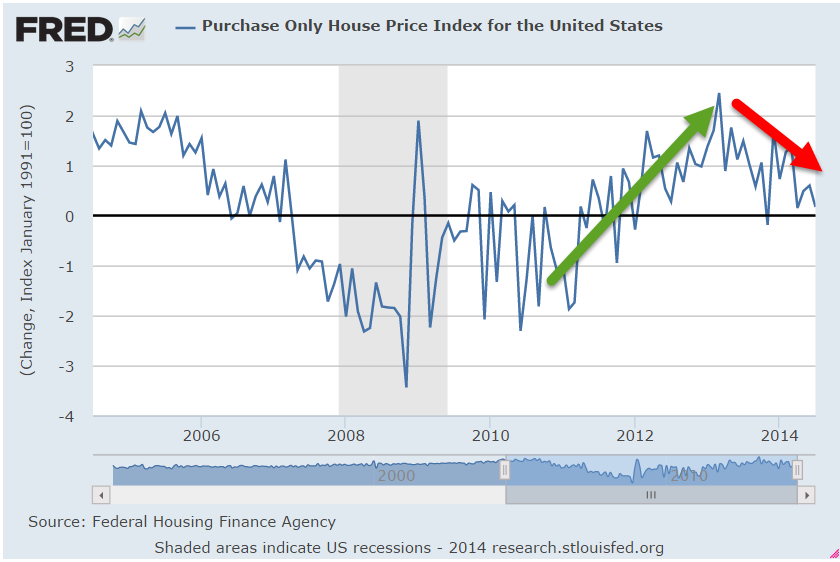

He sat down to eat, wondering what all the fuss in the market was. Checking the Bloomberg Calendar, he saw that it was the House Price index from the Federal Housing Administration that had dampened spirits. The monthly change was drifting down to zero, a sign of weakness. Although housing prices were still rising, the rise was slowing down.

A disappointment, George thought, but not a catastrophe. However, the market had been down for three days in a row. He finished his lunch and went into the living room. Mabel was reading a book.

“You know, Mabel, I think it’s just a short term thing. The bankers from the developed countries met last week and they kinda put out a wake up call to the market. I think there’s a bit more caution and common sense after that.”

“Well, as long as you’re watching it, dear.”

“You know, we did good this last year,” he reassured her.

“I just worry that it was too good. We should have taken some of that out of the market and put it somewhere safe.”

“Well, I’m keeping an eye on it,” he said. “I checked CD rates last week and they are paying like 1% for a one year CD. It just ain’t like it used to be. We just have to take some risk.”

They had a 3-year CD coming due in a month. He didn’t want to tell her that he was thinking about not rolling over the CD. Maybe buy a bond fund. She wouldn’t like that. For a time he had dabbled in some short to medium term trading but barely broke even. He had lost sight of his original goal – to keep their savings safe while taking some risk with the money. Fortunately, this insight had come to him toward the end of 2012. The market had been mostly up since then, rewarding those who sat out the small downturns.

Late Wednesday morning, Mabel could hear George on the side of the house clearing brush or some such thing. He said he was going to cut down an elm tree sapling that was growing near the house but when she went out to call him into lunch, he had cut everything but the elm sapling.

“I thought you were going to cut that down, dear.”

“Well, I was but the squirrels are using it to climb up to the old swamp cooler we have perched up there. You remember the litter from early this spring? Well, I think there’s another litter in there. I haven’t seen any young ones but there’s a squirrel carrying twigs up that sapling to the cooler. She’s even got a piece of one of my rags. Must’ve fallen out of my pocket.”

Mabel looked up at the platform George had mounted to the side of the house years ago. On top of the platform sat the old abandoned cooler. George had meant to take it down and disassemble the platform but then the squirrels had used it as a nursery this winter and neither of them had been able to dismantle it while the little ones were scampering around in and out of the cooler. Of course, George was supposed to take the cooler down during the summer but never got around to it. Now she saw that he had tied a cord from the platform to the sapling to bend the sapling close to the platform, making it easier for the squirrel to get from the tree to the platform.

She shook her head and said “George Liscomb, I hope you don’t let that sapling get out of hand. You know how elm trees are. They grow faster than a puppy.”

“Well, the tree won’t grow much during the winter and I’ll cut it down in the spring.”

“Ok, well, come on it. Lunch is ready. I heard on the radio that the market is up a lot today. Housing again. Maybe you were right about it being short term.”

“Well, of course, I’m right,” he made a grand gesture. “The squirrels will confirm that.”

His lunch plate held some broccoli spears and six, no more and no less, tater tots. “I know you don’t particularly like broccoli so I thought a few tater tots might ease the pain,” Mabel said with a slightly sardonic smile.

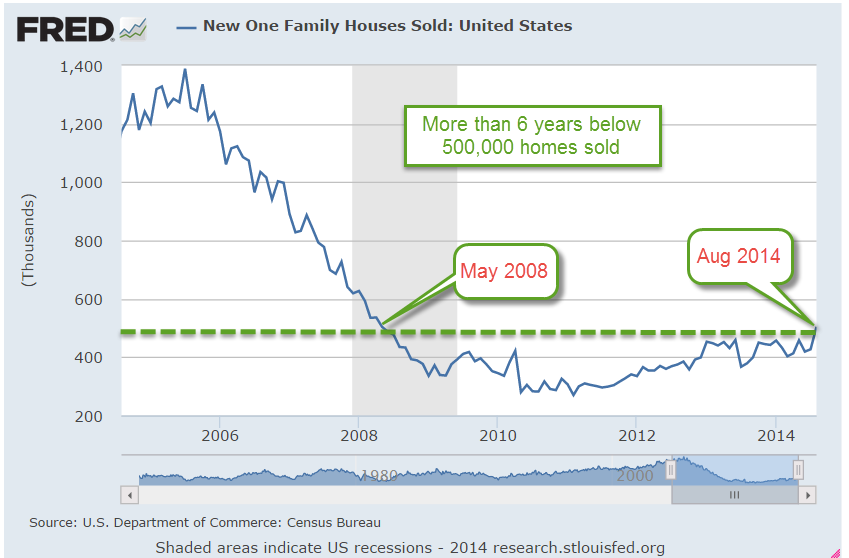

He laughed. “I’m married to a kind prison guard.” He sat down at the table, wondering what could have buoyed the market so much. Housing yet again. “Holy moly!” he called out to Mabel. He went into the living room to tell her the good news. “Finally, after more than six years, new homes are selling at a rate of more than half a million a year. That’s what’s got the market dancing.”

On Thursday, she found George working on the stream that he had built in the rock garden. A few feet from George a squirrel cautiously sipped water from the stream. The squirrel saw her and scampered up the nearby fence. “It’s remarkable how comfortable they are with you,” she told him. “I try to move slowly when I’m working,” George replied. “They seem to be less anxious.”

“What are you doing today?” she asked.

“Got a leak somewhere. I’ve lost about 15 gallons since last night. Still haven’t found it.”

“Well, you’re not going to like what going on in the market. It’s way down today and it’s not about housing.”

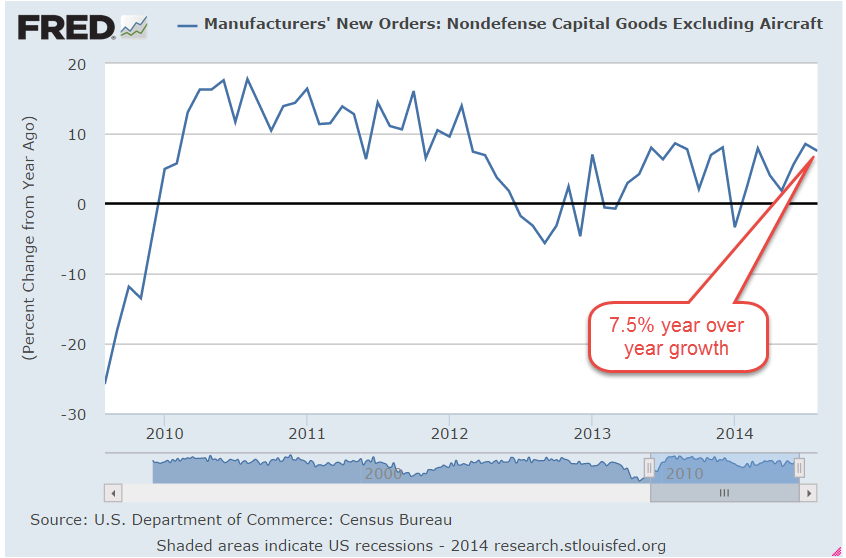

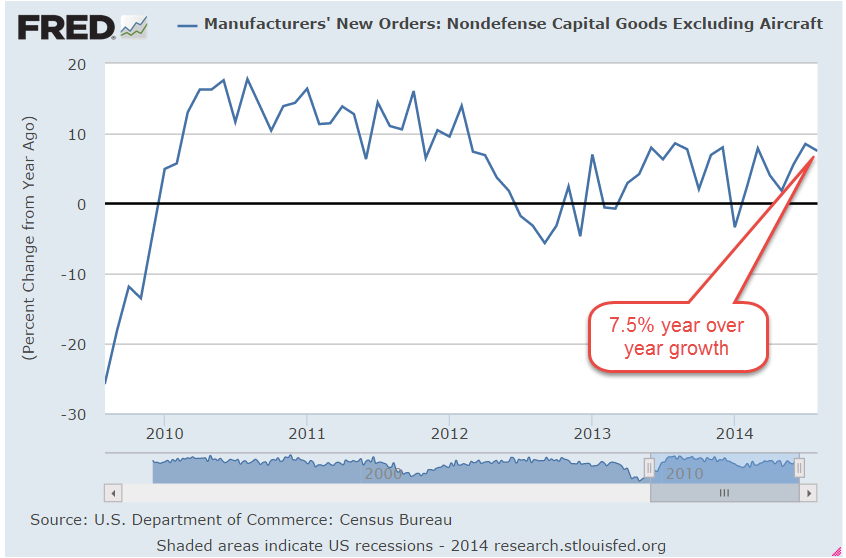

He followed her into the house and broke into a big grin when he saw what was for lunch. “Tuna fish!” Mabel had dressed up her famous tuna fish salad with lettuce, tomatoes, some green onions and put it open faced on some toasted bread. It was scrumptious. Not so the market. The SP500 was down about 1-1/2% on several news releases. The whopper was that Durable Goods Orders were down 18% in August from the previous month. But most of that drop was a decline in aircraft orders after a surge in those same orders in July. Aircraft orders were notoriously volatile. Year-over-year gains in non-defense capital goods, the core reading, were up almost 8%.

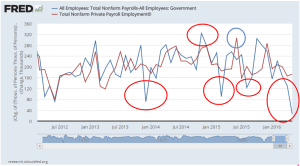

The weekly report of new unemployment claims had risen slightly but was still below 300,000. September’s advance reading of the services sector, the PMI Services Flash, was slightly less than the robust reading of August but still very strong. So what was causing these overreactions to news releases? The short term traders execute buy or sell orders within seconds of a news release. Computer algorithms trade within nanoseconds of the release. If new unemployment claims are up even by 1, the word “up” or “rise” or some variation will occur within the release. Sell. New home sales up? Up is good for this report. Buy. Why would the short-termers be so active this week? Because they are trading against each other. The mid and long termers, the portfolio managers, will take the stage at the beginning of next week to adjust their positions at quarter end when funds report their allocations.

Late Friday morning, Mabel stood out on the back deck, her mouth open at the sight of George hunched down as he came out of the shed in the backyard. Hundreds of wasps swarmed above him. He knelt down and closed the doors to the shed and hurried to her on the deck.

“My God, George! Are you all right?”

“Oh, yeah, no worries. Anything on me?” he asked.

“No.” There were just a few wasps visible outside the closed doors. “What on earth?!”

“Well, they’ve really built themselves a city since I was in there last,” George explained. He sat down on the deck. The shed was where they kept old tax records and camping gear that they hadn’t used in quite a long time but hadn’t given away or sold – just in case they went camping again. “I should have sprayed them earlier in the summer but it was such a small hive. Those doors get sun most of the day so they like it in there. They’re right above the doorway so they’re not bothering any of our stuff and I was able to stand up in the shed and they just left me alone.”

“I don’t care. What if I had gone out there to get something?!” she said angrily.

“Yeh, you’re right. I’ll take care of them this weekend. I was kinda waiting for the cold weather to do its job.” He held up his hands a couple of feet apart from each other. “That hive is like this, strung out along the studs that frame the doorway.”

“Why were you out there?” she asked.

“Well, I wanted to see if we still had the box that the TV came in a few years ago.”

“Didn’t you throw it out?” she asked.

“Well, I thought that in case we had trouble with the TV but then the box was behind a bunch of stuff and it was hard to get to and I guess I forgot,” he admitted.

“Well, come on it and eat your lunch. The market is up again today, I heard them say.”

George settled down at the kitchen table. A few salami slices, some macaroni salad, carrots, olives and crackers sat on the plate. “Working man’s antipasto, hey?”

“There are some sardines in there, too” she said.

“I have the best wife and cook in the world. Anthony Bourdain, move ovah! Mah honey’s takin’ ovah!”

Mabel laughed. “Now let me get back to my book. Second to last chapter and I think the niece did it. I haven’t trusted her since the first chapter.”

The 3rd estimate of 2nd quarter GDP had been revised up from 4.2% to 4.6%, helping to compensate for the weak first quarter. Good stuff, thought George. The U. of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Survey had risen in September to 84.6 from August’s 82.5. Confident consumers buy stuff, a good sign. Anything above 80 was welcome and more was better. To round out the daily trifecta of news releases, corporate profits for the second quarter were revised upward. The year over year gain without inventory and depreciation adjustments was 12.5%. Not spectacular but solid.

Even with Friday’s triply good news, the market closed below what it opened at the previous day. This was usually an indication that the short term downward trend in the market might have a little way to run. Then he promised Mabel that he would get rid of the wasps this weekend, and yes, he would be careful. Did she remember seeing the wasp spray that he bought earlier that summer?