April 7, 2019

by Steve Stofka

In 1971 former President Nixon announced that the U.S. was abandoning the gold standard of fixed exchange that had existed for almost thirty years. Within a short time, other leading nations followed suit. Each nation’s currency simply traded against each other on a global currency, or FX, market.

Since oil was priced in dollars and the world ran on oil, the U.S. dollar became the world’s reserve currency. Each second of every day, millions of US dollars are traded on the international FX markets. The demand for US dollars is strong because we are a productive economy. The euro, yen and British pound are secondary currency benchmarks.

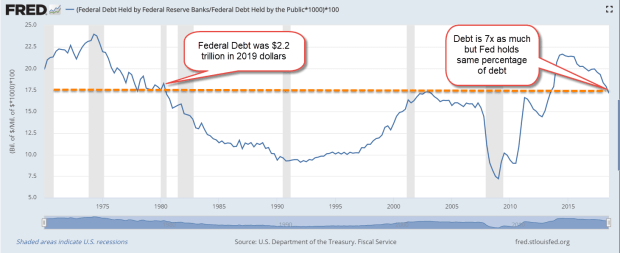

When the U.S. wants to borrow money from the rest of the world, the U.S. Treasury sells notes and bills collectively called “Treasuries” to large domestic and foreign banks who “park” them in their savings accounts at the Federal Reserve (Fed), the U.S. central bank (Note #1). The phrase “printing money” refers to a process where the Federal Reserve, an independent branch of the Federal Government, buys Treasury debt on the secondary market. It may surprise many to learn that the Fed owns the same percentage of U.S. debt as it did in 1980. The debt in real dollars has grown seven times, but the percentage held by the Fed is the same. That is a powerful testament to the global hunger for U.S. debt. Here’s the chart from the Fed’s FRED database.

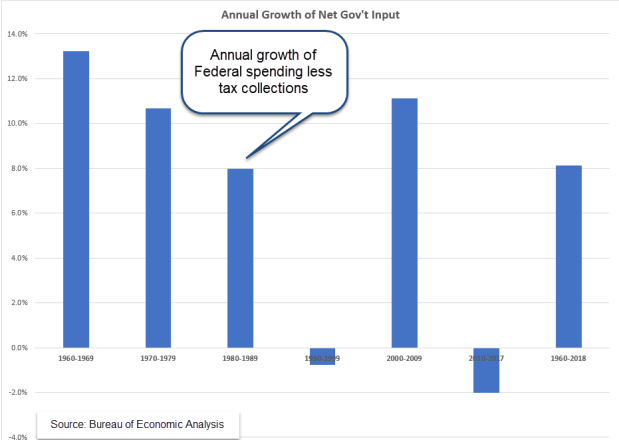

In 1835, President Andrew Jackson paid off the Federal debt, the one and only time the debt has been erased. It left the country’s banking system in such a weak state that subsequent events caused a panic and recession that lasted for almost a decade (Note #2). Government debt is the private economy’s asset. Paying down that debt reduces those assets.

About a third of the debt of the U.S. is traded around the world like gold. It is better than gold because it pays interest and there are no storage costs. Foreign businesses who borrow in dollars must be careful, however. They suffer when their local currency depreciates against the dollar. They must earn even greater profits to convert their local currency to dollars to make payments on those dollar-denominated loans.

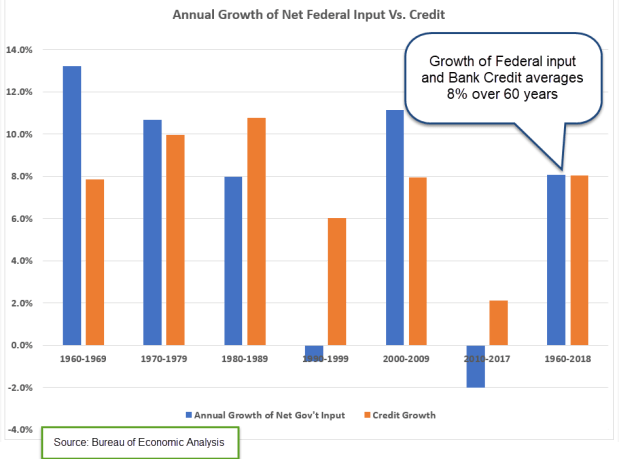

Each auction of Treasury debt is oversubscribed. There isn’t enough debt to meet demand. In a world of uncertainty, the U.S. government has a long history of respect for its monetary obligations. As the reserve currency of the world, the U.S. government can spend at will. Even if there were no longer a line of domestic and foreign buyers for Treasuries, the Federal Reserve could “purchase” the Treasuries, i.e. print money. Let’s look at the difference between borrowing from the private sector and printing money.

When the private sector buys Treasuries, it is effectively trading in old capital that cannot be put to more productive use. That old capital represents the exchange of real goods at some time in the past. In contrast, when the government spends by buying its own debt, i.e. printing money, it is using up the current production of the private sector. This puts upward pressure on prices. Let’s look at a recent example.

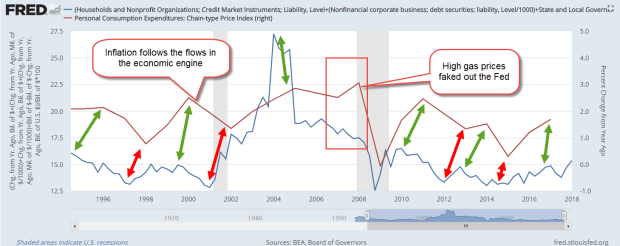

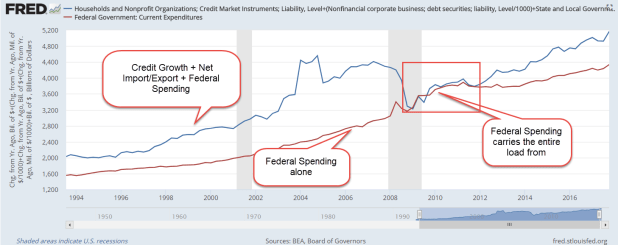

Quantitative Easing (QE) was a Fed euphemism for printing money. During the three phases of QE that began in 2009, the Fed bought Treasury debt. That was an inflationary policy that countered price deflation as a result of the Financial Crisis. In August 2009, inflation sank as low as -.8% (Note #3). It was even worse, but inflation measures do not include the dividend yield on money. To many households, inflation felt like -2% (Note #4). The Fed’s first round of QE did provide a jolt that helped drive prices up by 3% and out of the deflationary zone.

During the five years of QE programs, the Fed continued to fight itself. The QE programs pushed prices upwards. Near zero interest rates produced a deflationary counterbalance to the inflationary pressures of printing money. Because inflation measures do not include the yield on money, the Fed could not read the true change in the prices of real goods in the private sector. The economy continues to fall below the Fed’s goal of 2% inflation. There are still too many idle resources.

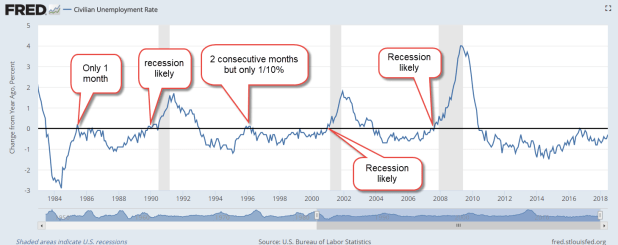

Leading proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) remind people that yes, the U.S. can spend at will, but that it must base its borrowing on policy rules to avoid inflation. A key component of MMT is a Job Guarantee (JG) program ensuring employment to anyone who wants a job. A JG program may remind some of the WPA work programs during the Great Depression. Visitors to popular tourist attractions, from Yellowstone Park in Wyoming to Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, use facilities built by WPA work crews. Today’s JG program would be quite different. It would be locally administered and targeted toward smaller public works so that the program was flexible.

The U.S. government has borrowed freely to go to war and has never paid that debt back. Proponents of MMT recommend that the U.S. do the same during those times when the private economy cannot support full employment. That policy goal was given to the Fed in the 1970s, but it has never been able to meet the task of full employment through crude monetary tools. With an active program of full employment, the Fed would be left with only one goal – guarding against inflation.

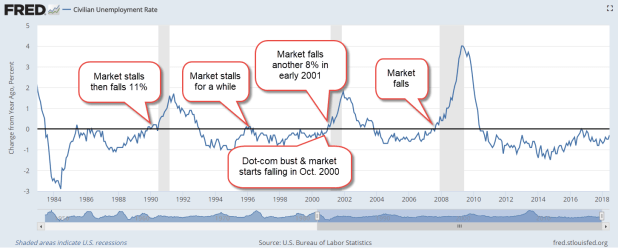

There are two approaches to inflation control: monetary and fiscal. Monetary policy is controlled by the Fed and includes the setting of interest rates. If the Fed’s mandate was reduced to fighting inflation, it could more readily adopt the Taylor rule to set interest rates (Note #4).

Fiscal policy is controlled by Congress. Because taxation drains spending power from the economy, it has a powerful control on inflation. However, changes in tax policy are difficult to implement because taxes arouse passions. We are familiar with the arguments because they are repeated so often. Everyone should pay their “fair share,” whatever that is. Some want a flat tax like a head tax that cities like Denver have enacted. Others want a flat tax rate like some states tax incomes. Others want even more progressive income taxes so that the rich pay more and the middle class pay less. Some claim that income taxes are a government invasion of private property rights.

Because tax changes are difficult to enact, Congress would be slow to respond to changes in inflation. The Fed’s control of interest rates is the more responsive instrument. The JG program would provide stability to the economy and reduce the need for corrective monetary action by the Fed. The program would help uplift those in marginal communities and provide much needed assistance to cities and towns which had to delay public works projects and infrastructure repair because of the Financial Crisis. As sidewalks and streets get fixed and graffiti cleaned, those who live in those areas will take more pride in their town, in their communities, in their families and themselves. This makes not just good economic sense but good spiritual sense. We can start small, but we must start.

////////////////////////

Notes:

1. Twenty to twenty-five times each month, the Treasury auctions U.S. government debt. Many refer to the various forms of bills and notes as “treasuries.” A page on the debt

2. The Panic of 1837

3. The Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation is the Personal Consumption Expenditure Index, PCEPI series.

4. The annual change in the 10-Year Constant Maturity Treasury fell below -1% at the start of the recession in December 2007 and remained below -1% until July 2009. FRED series DGS10. John Maynard Keynes had recommended the inclusion of money’s yield in any index of consumer demand. In his seminal work Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947), economist Paul Samuelson discussed the issue but discarded it (p. 164-5). Later economists did the same.

5. The Taylor rule utility at the Atlanta Federal Reserve.