To some extent, the Federal Reserve considers itself government. Other times, when it serves, it considers itself not government. – Philip Coldwell, President FRB Dallas 1968-74

September 2, 2018

by Steve Stofka

The nations of the world are the gods of Mt. Money, most of them with central banks who administer the credit and currency of each nation. Like the ancient Mt. Olympus of Greek lore, there is competition and a hierarchy among the gods. Currently the U.S. is the top god of Mt. Money. Central banks manage credit by changing the interest rate, or price, that they will charge the demi-god banks within the nation’s borders. The banks, however, do not perfectly distribute the intentions of the central bank. Acting as intermediaries, the banks filter monetary policy and have a more direct effect on the economy. In this intermediary role, banks control the draining of Federal taxes generated by the economic engine.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve (Fed) is the central bank of the Federal government, an independent agency created by Congress which has given it two targets: promote full employment and stable inflation. To meet those goals, Fed economists must gauge the strength of the economy, a difficult task, and estimate an ideal state of the economy, an even more difficult task.

Each August the Federal Reserve holds an economic summit at Jackson Hole in Wyoming. The newly appointed head of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, is the first non-economist leading the central bank in 39 years. His paper (Note #1) is plain spoken and illustrates the difficulty of reading an economy in real time. As such, I think he will be a gradualist, someone who advocates measured moves in interest rates unless there is a more abrupt shift that requires a stronger policy tonic.

Powell uses the analogy of a sailor steering the waters by reading the stars. The waves and weather can make real time observations unreliable, yet the sailor must make decisions that steer his course. Optimizing employment is one of the two missions that Congress has given the Federal Reserve. The Fed must make a real-time estimate of what they think is the optimum or natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU) and adjust interest rates to help align the actual unemployment rate to the natural rate. Powell presented a chart that compares the actual rate of unemployment to NAIRU as it was estimated at the time, and the “hindsight” NAIRU as economists now calculate it. (Note #2) The speech balloons are mine.

On page seven, Powell writes that, in the past, the central bank “placed too much emphasis on its imprecise estimates of [NAIRU] and too little emphasis on evidence of rising inflation expectations.”

Note the final word – expectations. Measuring what will happen is especially difficult because it has not happened. Probability methods can help but an economy has many more inputs than a dice game. One category of estimates are surveys of guesses about what will happen in the future, but these overstate actual inflation [Note #3]. A second category uses market prices. One method uses the price that buyers are willing to pay for a Treasury Inflation Protected Security (TIPS) (Note #4) In my July 22nd post, I introduced another market method – the net flow of money into the economic engine (Note #5)

Credit expansion has been poor since the Financial Crisis. The Fed cannot force banks to increase or decrease their loan portfolios by changing interest rates. In the years following the Financial Crisis, the Fed was frustrated by this inability, called “pushing on a wet noodle.” Interest rates are the carrot. The stick is a complex regulatory process that raises or lowers asset leverage ratios to encourage or discourage lending (Note #6).

The Fed manages credit flow through asset sales and purchases. While the central banks of other countries can buy stocks and commodities, the Fed is limited to buying debt, including foreign currencies, from its member banks (Note #7).

The Fed has the extraordinary power to purchase or sell the reserves of its member banks without their consent. Like the Fed, you or I can increase the reserves of a bank by depositing money in the bank (Note #8). What we can’t do is lower those reserves by writing our own loans. However, credit card companies, who are underwritten by banks, do provide us with a line of credit that we can draw on by using our cards. During the Financial Crisis, credit card debt jumped $50B, or 15%, because card holders reduced their payments by that much. In response, credit card companies reduced credit card limits by 28% (Note #9). While the Fed encouraged banks to loan, the behavior of consumers and businesses did the opposite. Consumers and businesses were more powerful than the Fed.

The banks administer or filter Fed policy in their interactions with consumers and businesses. If a bank must pay higher interest for its funds, then it will charge higher interest rates for consumer and business loans. Interest is the price for a loan. When the price rises, the supply for loans rises (banks make more profit on the spread) but demand for loans falls. The reverse is not true, as the data of the past decade has shown. When the price falls, the supply of loans falls while the demand increases.

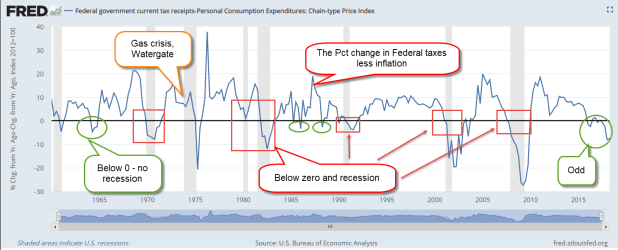

Less credit expansion results in a slower economic engine, which generates less Federal tax revenue. For the engine to run properly, the internal pressure must remain stable. Inflation is one gauge of that internal pressure. The annual growth in Federal tax revenue must be equal to or greater than the inflation rate. When it is not, the engine begins to stall. In the graph below, I’ve charted the annual growth in Federal tax revenue less the inflation rate. Note the periods when this metric dropped below zero. In most cases, recession follows. Look at the right side of this chart. There has never been a time when the reading is so far below zero without a recession. That is a cautionary note.

The Fed must look through the fog of the future before it deploys its money super powers. In the face of this, the Fed must act with humility and a practical caution. Once it has decided on a strategy, the banks modify its implementation because they obey three masters: the Fed, their customers and their stockholders. Actual monetary policy becomes not the work of a select few in the Federal Reserve but an emergent composite of policy force and practical friction.

/////////////////////////

1. Powell’s speech is 14 pages double-spaced with several pages of charts and references.

2. For thirty years, from 1955 to 1985, the gap between the real-time estimate of NAIRU and the hindsight estimate is 1-1/2%, an error of 25%. In the 1990s economists’ models were more accurate. The estimate of NAIRU and its validity is debated now as it was in 1998 when Nouriel Roubini referenced several views on the topic.

3. A one-page Fed article on survey and market methods of measuring inflation expectations.

4. A one-page Fed article on long-term inflation expectations using the implied rate of TIPS treasury bonds – currently it is 2.1%. Vanguard article explaining TIPS bonds.

5. The net flows of credit growth, federal spending and taxes precedes inflation by several months (July 22 blog post).

6. Credit growth has been flat for the past decade as I showed in this July 15th post.

7. In conjunction with the Treasury, the Federal Reserve may buy foreign currencies to correct disruptive imbalances in interest rates. A NY Fed article explaining the process.

8. When we deposit money in a bank, its reserves, or cash balance, increases on the asset side. It incurs an offsetting liability of the same amount because the bank owes us money. We have, in effect, loaned the bank money. When so many banks collapsed before and during the Great Depression, people came to realize the true nature of depositing money in a bank. The banks could not pay back the money that depositors had loaned them. The creation of the FDIC insured depositors that the money creating powers of the Federal government would stand behind any member bank. My mom grew up during the Depression era and passed on the lessons learned from her parents. She would point to the FDIC Insured decal on the bank window and tell us kids to look for that decal on any bank we did business with in the future.

9. Credit card companies lowered limits. See page 8. Oddly enough, this Fed study found “we have little evidence on the effect of such large declines in housing wealth on the demand for debt.” Page 9. NY Fed paper written in 2013.