June 22, 2014

This week I’ll look at interest rates and various models of evaluating both the stock market and housing.

*****************

GDP Growth Revised

This past Monday, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) cut estimates for this year’s economic growth in the U.S. to 2% from 2.8%. IMF cited a number of headwinds: the severe winter, weakness in housing, some fragility in the labor market. It recommends that the central bank keep rates low through 2017. Expectations were that the Federal Reserve would begin raising interest rates in mid 2015. Some recommendations in the report will be met with antipathy or a polite “thanks for letting us know”: raising the minimum wage and gasoline taxes.

******************

Fed Don’t Fail Me Now

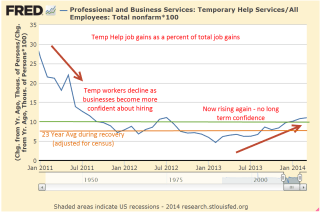

As expected, the Federal Reserve decided to leave the target interest rate at the extremely low range of 0% to .25% that it has held in place since the beginning of 2009. Congress has given the Fed a dual mandate: keep inflation reasonable and promote full employment. It is this second half of the mandate that presents some problems as the FOMC looks into their crystal ball. The Labor Force Participation Rate is the percentage of those working to those old enough to work. It has declined from 66% at the beginning of the recession to less than 63% today.

As economic conditions improve and job prospects brighten, how many of those who have dropped out of the labor force will return? If workers return to the labor force, actively seeking work, that increased supply of labor will naturally curb wage increases and reduce upward pressure on inflation. However, if the decline in the participation rate is more or less permanent for several years to a decade, then a stronger economy will create more demand for workers, who can demand more money for their labor, which will contribute to inflation.

**********************

401K Retirement Plans

The Financial Times reported projections of negative cash flows in 401K plans by 2016 as boomers convert their pension plans to IRAs when they retire. Retirees tend to have a much more conservative stock/bond allocation and may force institutional money managers to liquidate some equities to meet the outgoing cash flows. An ominous speculation at the end of the article is that regulations could be put in place to slow the conversion of 401Ks to IRAs. Whenever the finance industry needs a friend in Washington, they can be sure to find one.

*********************

Stock Market Valuation

It has been 32 months without a 10% correction in the SP500 market index. The post World War 2 average is 18 months. Is the stock market overvalued? I will review a common metric of value and develop an alternative model of long-term value.

Probably the most widely used metric of stock valuation is the Price/Earnings, or PE, ratio. If a stock sells for $100 and its annual earnings are $6, then the P/E ratio is 100/6, or a bit above 16. The average PE ratio is 15.5 (Source). Companies do not pay all of those earnings in the form of dividends to investors. That is another metric, called the Price Dividend, or P/D ratio, that I wrote about last year.

Fact Set provides an analysis of the past quarter’s earnings of the SP500 companies, as well as projections of current and next year’s earnings. Earnings growth estimates for this year range from 30% (yikes!) for the telecom sector to a bit over 3% for utilities. The health care sector tops estimates of revenue growth at about 8%, while the energy sector is projected to have negative growth. The basic materials sector tops the 2015 list of earnings growth at 18% and the utilities sector again takes the bottom rung on the ladder with almost 4% growth.

The SP500 is priced at 15.6x forward 12 months earnings, which is above the five year and 10 year averages of less than 14x (Fact Set Report page) but just about the 100 year average of 15.5.

Robert Shiller, a Yale economist and co-developer of the Case-Shiller housing index, uses a smoothing technique for calculating a Price Earnings ratio and makes his data spreadsheet available. His team calculates the 10 year average of real, or inflation-adjusted, earnings and divides the inflation adjusted price of the SP500 by that average to arrive at a Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings, or CAPE, ratio.

Using this methodology, the market’s CAPE ratio is 25, above the 30 year ratio of 22.91 and the 50 year ratio of 19.57. In 1996, the market was trading at this same ratio, prompting then Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan to make his infamous comment about “irrational exuberance.” The market continued to climb till it reached a nosebleed CAPE ratio of 43 in early 2000. It took another 7 months or so before the SP500 began its descent from 1485 to 900, a drop of 40%, over the next two years. There is no automatic switch that flips when a market becomes overvalued. People just get up from their seats and start to leave the theater.

In most decades, this methodology works well to arrive at a longer term perspective of the market’s price. However, some argue that when severe downturns occur, this methodology continues to factor in the downturn’s impact long after it they have passed. In 2008 and 2009, SP500 index annual earnings crashed from above $80 down to $60, a precipitous decline that is still factored into the ten year framework of the CAPE method.

So I took Mr. Shiller’s earnings figures and did some magic on them. I took away most of the downturn in earnings during a 3 year period from 2008 – 2010.

Bye, bye earnings dive. Hello, stagnating earnings. The chart shows a slight downturn in earnings, then flat-lines in the pretend world of 2008 – 2010, where the steep recession never happened.

Instead of a deep crater formed in the markets by the financial panic in late 2008, the stock market slid downward over several years before rising again in early 2012. Can you hear the soft sounds of flutes echoing in the mountain meadows of this pretend world?

Using this pretend data, I recalculated today’s CAPE ratio at 22, below the actual 25 CAPE ratio. What should be the benchmark in this pretend world? The 100 year average includes the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War 2, which naturally lowered PE ratios. A 50 year average includes the Vietnam War and high inflation, particularly during the 1970s and early 1980s. As such, it is less comparable to today’s environment marked by low inflation and the lack of major hostilities.

So, I ran a 30 year average of our pretend world, from 1984-2013, and calculated a 30 year average of 23, close to the real 30 year average of 22.9! It shows the relatively small effect that even momentous events have on a long term average of the CAPE ratio, which is why Robert Shiller advocates its use to calculate value and establish a comparison benchmark within a longer time frame. In the real world, the market’s CAPE ratio of 25 is above that 30 year average.

Let’s put aside the world of soft market landings and mountain meadows and look at what I call the time value of the market. I picked January 1980, a point almost 35 years in the past, as a starting point. Then I divided the SP500 index by the number of months that have passed since that starting point. This gives me a ratio of value over time. If an investor buys into the market when its value is above a long-term average of that ratio, we can expect a lower long-term rate of return.

The 20 year average is 3.98, just a shade above the 20 year median of 3.91, meaning that the highs and lows of the average pretty much cancel out. Note also that it is only in the past year that the market value has risen above the 20 year average of this ratio.

But we cannot look at a time value of any investment without considering inflation, which erodes value over time. When we add the Time Value Ratio and the Consumer Price Index (CPI), we find that the current market is priced slightly lower than both the 20 year and 30 year averages.

Historically, as this ratio has risen more than 25 – 30% above its long-term average, the market peaked. Today’s ratio is just about average.

So, is the market overvalued? Based on CAPE methodology, yes. Fairly valued? Based on expectations of earnings growth this year and next, yes. Undervalued? Probably not.

Common Sense recently published the best and worst 10 and 20 year returns on a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio mix. This balanced approach had a 2 – 3% annualized gain even during the Depression years when the stock market lost 80 – 90% of its value. It should be a reminder to all investors that trying to assess the true value of the stock market is perhaps less important than staying diversified.

************************

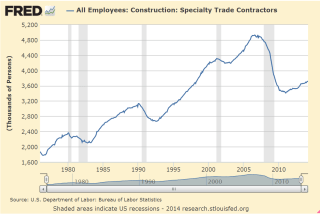

The P/E of Housing

Home builders broke ground on almost 1.1 million private residential units in April, a 13% increase over last year. Called Housing Starts, the series includes both multi-family units and single family homes. The pace slowed a bit in May but still broke the 1 million mark. As a percent of the population, we just aren’t building as many homes as we used to.

For most of us, our working years are about 60% of our lifespan. Hopefully, our parents took care of our income needs for the first 20% of our lifespan. During our working years, we hope to save enough to generate a flow of income for the last 20% of our lifespan. Those savings, which include private pensions and Social Security, are like a pool of water that we accumulate until we start turning on the spigot to start draining the pool. We turn a stock or pool of savings into a flow of income.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics uses a metric called Owner Equivalent Rent (OER) in their calculation of the Consumer Price Index. This concept treats a home as though it were generating a phantom income equivalent to the rents in that local real estate market. We can use this concept to value a house. The future flows from a stock can be used to generate an intrinsic current value for the house.

As an example: a house which would generate a net $12000 a year in income, whether real or phantom, after taxes and other expenses, is worth about 16 times that net income, according to historical trends calculated by the ratings agency Moodys. In this case, the house would be worth about $200K.

Coincidentally, this is the average P/E ratio of the stock market. Historically, stocks have been valued so that the price of the company’s stock has been about 16 times the earnings flow from the company’s activities. If a primary residence generates 6% in tax free income and 3% in appreciation, the total annual return on owning a house free and clear is more than the average annual return of the stock market. The housing boom and bust may have given many younger people the impression that home ownership is a debt trap. It may take a decade for the housing industry to recover from this perception.

**************************

Takeaways

The Fed is likely to keep interest rates low past mid-2015 but is watching the Labor Participation Rate for early indications that rising wage pressures will spur rising inflation.

The stock market is slightly overvalued or fairly valued depending on the metric one uses.

On average, a house has a value multipler that is similar to the stock market but generates a higher after tax income.

Next week I’ll take a look at some long term trends in education spending and tuition costs.