August 11th, 2013

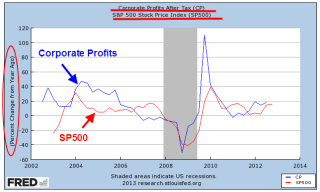

Last week I wrote about viewing trends in the market through the lens of hard cold cash; that is, the dividends paid by the companies in the SP500. Today, I’ll revisit that subject in a bit more depth. Beginning in the last quarter of 2008, reported earnings of companies in the SP500 dropped precipitously, plunging about 90% in the first two quarters of 2009.

The portion of those earnings paid as dividends fell 24% from peak to trough, far less than earnings.

Robert Shiller, a Yale economist and co-developer of the Case-Shiller housing index, uses a smoothing technique for calculating a Price Earnings ratio and graciously makes his data available. He calculates the 10 year average of real, or inflation-adjusted, earnings and divides the inflation adjusted price of the SP500 by that average. Because of the low inflation environment for most of the past decade, the difference between the two earnings figures, nominal and real, is slight.

The drop in corporate earnings was extreme, more so than any recession, including the Great Depression of the 1930s. In the 2001 recession, earnings declined to about half of their prerecession peak. In the recession of the early nineties, it was about 30%. In the back to back recessions of the early 1980s, corporate earnings fell about 25%.

While Shiller’s method evens out earnings, it has one drawback, one that no one could have foreseen until 2008 simply because it had never occurred. The severity of the decline in earnings skewed the ten year average of earnings down over the 2002 – 2012 period. Since the earnings average is the divisor in the Shiller P/E ratio, it correspondingly makes the ratio of the price of stocks a bit higher than it might otherwise be.

For that reason, I’ll look at a less volatile ten year average of dividends; that is, the inflation adjusted price of the SP500 divided by the ten year average of inflation adjusted dividends.

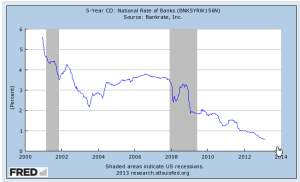

Today’s market prices are at the twenty year average of the real price dividend ratio, which is about 61. For a number of factors, market prices as measured by this dividend ratio are higher for the past twenty years than the thirty year average of 51. The tech and real estate bubbles over-inflated prices but investors have been willing to pay more for stocks as bond yields have declined steadily from their nosebleed levels of thirty years ago.

Let’s crank up the time machine and go back a year. Here are a few quotes from an October 13, 2012 Reuters article after the market had dropped about 2%:

“Central bank-fueled gains took markets within reach of five year highs in September, but now U.S. stock market participants are shifting their focus back to corporate outlooks, and the picture is not pretty.”

The article quoted the director of investment strategy at E-Trade Financial, Michael Loewengart: “The overall tone is so pessimistic that we may see some upside surprises, but we could still suffer considerable losses if the news is bad.”

“Profits of SP500 companies are seen dropping 3% this quarter from a year ago, the first decline in three years”

It was close to being almost the end of the world. As you read various comments in the news, keep in mind that these remarks are coming from active traders who see a 5% drop as catastrophic if they have not anticipated it through options and other hedging strategies. For longer term investors, a 5% drop after a 5% rise over several months is more yawn provoking than cataclysmic.

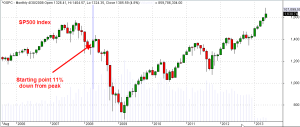

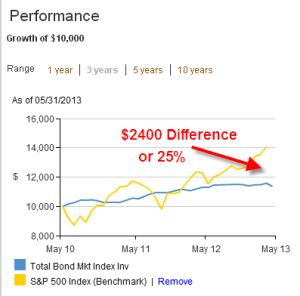

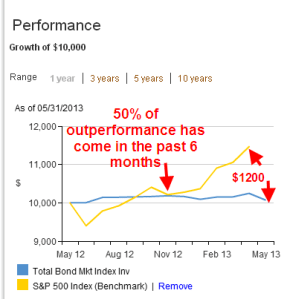

Through the middle of November 2012, the market would drop another 5%. Slowing corporate profits and the looming – yes, looming – fiscal cliff spooked investors. Then, on the hopes that the Fed would do something to offset these negatives, the market regained the 5% lost in the previous month. In mid-December, the Fed announced that it would double its bond purchasing program and the market has been rising since, gaining 20%. Has this been a new bubble, one we’ll call the “Fed Bubble?” Some say yes, some say no.

As we read the daily news, let’s keep in mind that in ten years we will have forgotten most of it. Some fears will seem silly, some may seem prescient. Each day there are many predictions, some like this one from December 30, 2001: “By the year 2003, there will be 2 types of businesses, those doing business on the internet and those out of business.” (Sorry, I didn’t write down the attribution). Some predictions will seem rather silly like the one in March 2009 that the SP500 would be below 500 in a month.

Farmers and businessmen in ancient Rome consulted soothsayers who threw chicken bones and read the pattern in the bones to tell their clients whether there would be rains in the spring and how hot the summer would be. Sometimes they were right, sometimes they were wrong.

Each day the market goes up – or it goes down. For the past twenty years it has gone up 54% of the time, down 46% of the time. Going up seems like an odds on favorite but this is complicated by the fact that the market usually goes down faster than it goes up. There is also a well documented behavioral phenomenon of risk aversion; people respond more emotionally to loss than we do to gains.

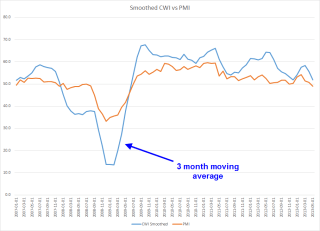

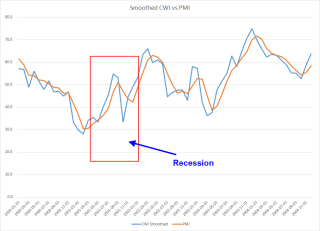

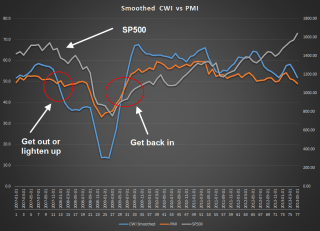

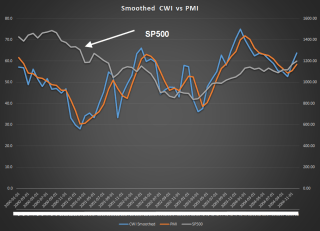

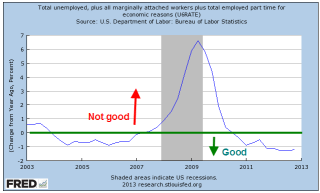

This past Monday came the release of the ISM monthly survey of Non-Manufacturing businesses. Like the manufacturing survey released a few days earlier, this index also surged upward in July, a welcome relief after the declining numbers in June. I’ve updated the composite CWI that I introduced a while back and compared it to the SP500 and the Business Activity Index of the Non-Manufacturing Survey.

This composite index is weighted 70% to non-manufacturing, 30% to manfacturing. Because this CWI relies on past months’ activity as a predictor of future conditions, it responds with less volatility to a one month surge in survey data. As we can see, the tepid growth that began appearing this past spring is still showing in this index, although it is a strong 55.5, indicating sure footed, if not surging, growth. It has been above the neutral mark of 50 since August 2009.