November 23, 2014

A strong wind from the southwest blew into town, chasing the cold weather out onto the great plains east of Denver. Most of the trees had given up their leaves as the days grew shorter but the elm trees had stubbornly held onto their leaves, still green far into November. The turning of color began during the cold snap of the previous week and now the great gnarly giants began to release their leaves to the winds. Busy at work for many years, George had hired out the autumn cleanup. Now that he was retired, he was becoming more attuned to the daily and seasonal rhythms of the plants and animals in the neighborhood.

“Leave me a small bag of leaves, dear,” Mabel asked. She would dry them out, then arrange them into an autumn harvest theme. George knew he needed to bring up the renewal of the CD with Mabel before her attention became entirely focused on the holidays. She would set up the card table in the dining room and the season’s decorating would begin.

George had spent a lifetime assessing risk for the insurance of commercial buildings, which are dependent on the municipal services available to them – the fire, police, utilities, transportation, communications, and medical facilities that reduce either the risk or cost of damage. George had given too many presentations at city council meetings or at the city planning board, outlining the cost benefits of municipal improvements. Unlike the federal government with its seemingly limitless ability to borrow money, state and local governments had to live with real budget constraints.

George categorized himself as a prudent judge of risk. However, he knew that most people he had met in his line of work thought they were prudent. If asked, “Do you think you are more or less prudent than average?” most would answer that they are above average. It was the Lake Wobegon effect, where everyone’s child was above average. We couldn’t all be above average.

Mabel’s experience as a school principal had given her a firm grounding in budgets and accounting, but she was reluctant to take much risk with their personal savings, preferring CDs and savings accounts. She was not alone. In a recent Wall St. Journal blog was a study showing that 1/3 of IRA accounts had no stock exposure.

Fifty-six percent of IRA owners had either all their IRA money in stocks or absolutely none of that money in stocks in both 2010 and 2012, according to a study by the Employee Benefit Research Institute of data on 25.3 million accounts. (It was 33.2% at the no-equity end of the spectrum and 22.5% at the all-equity end.)

In today’s low interest environment these accounts paid little interest but their value was secure. If the 2008 financial crisis had happened when he and Mabel were in their thirties and had little in savings and several decades of paychecks to come, the emotional effect probably would have lessened with time. Coming as it did right before their retirement, the crisis had shaken their faith in anything whose principal was not guaranteed. Their losses during the crisis had been lessened simply because Mabel had been so insistent on selling what stocks and bonds they had in September of 2008.

She had blamed the crisis on Bush, whom she thought to be one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. George, who followed the markets and financial news more closely, made several attempts to give Mabel a more balanced assessment but she was adamant. “No rules! No regulations! This dummy for a president is finding out what happens when there are no rules or regulations! It’s like high school with no one in charge!” As stock prices continued to sink over that winter, George was thankful that they had avoided any additional losses. On the other hand, they had avoided most of the subsequent gains in the past seven years.

He mentally rehearsed his presentation. The $50,000 CD was coming up next week. It had paid a paltry 1.1%. He checked one year CD rates. Chase was offering 1/100th of 1%, Wells Fargo 5/100ths. Had George read that right? He checked the decimal points. Sure enough, .01% and .05%. In short, “We don’t want your money!” A savings deposit or CD was essentially a loan to the bank, so why would any bank want money from Ma and Pa Liscomb when they could get it for almost free from the U.S. government? So, he would start off telling Mabel about the low interest rates.

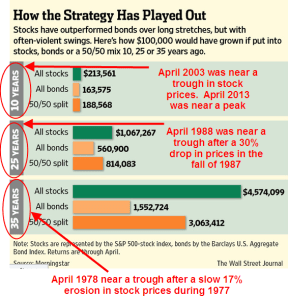

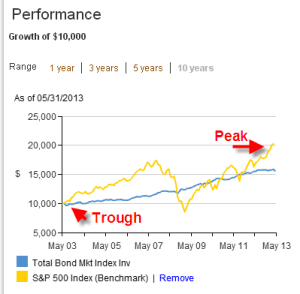

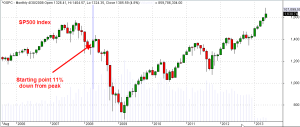

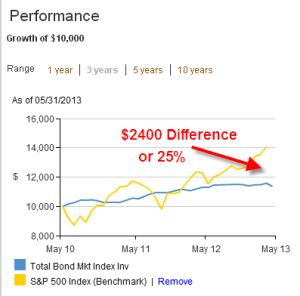

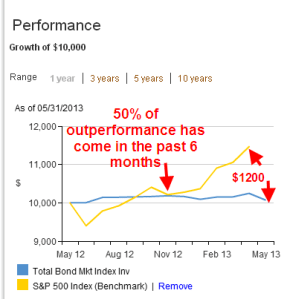

The next part of his presentation would be a cautionary tone of risk and reward. He would tell Mabel that the stock market was like a wagon train. Well, maybe that was too poetic. She might give him her “gimme a break” look. He would hold up his hand and ask for some patience. Different wagon trains take different paths across the country. The bond wagon train takes the southern route. The terrain is flatter but the distance is longer. The stock wagon train takes the more direct route across the mountains and valleys. He’d show her the chart of the SP500 as it went up and down the hills and valleys.

“Yeh,” she would say, “what I don’t like are the steep valleys.” That’s when he would show her his zig-zag chart. Do you see how bonds zig when stocks zag? he would say. This way, bonds counterbalance some of the risks in the stock market.

“So what happened in 2008?” she would say with a healthy dose of skepticism in her voice. “Well, that was unusual,” he would say. “Everything fell. Even it did happen again, it is unlikely to stay that way for more than a few months or at most a few years. If a crisis like that happened again and stayed that way for several years, we’d be more worried about getting food and gas, not about paying for it,” he’d say. Ok, maybe that would be an overstatement, but maybe not.

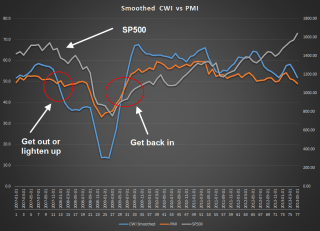

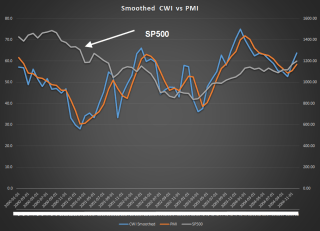

“But stocks have already gone up for the past few years,” she might say. “Some people are saying that it’s a bubble.” Then he’d mention all the good economic signs. Manufacturing and services were both strong. Industrial Production continued to rise and has been above 2007 levels for more than a year.

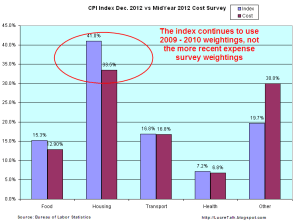

Sure, there were signs of weak consumer demand. The Consumer Price Index had risen only 1.7% over the past year. Falling gas prices had helped keep a lid on raises in the CPI and was putting extra money in consumers’ pockets. It was not only lifting airline profits but contributing to lower costs for a lot of companies. The Homebuilders association was reporting strong confidence among their members and existing home sales were at a stable level.

George wouldn’t tell her one thing that concerned him. It was a long term phenomenon, a growing caution that George attributed to the aging of the population. People put money in safe money accounts like savings, CDs, money markets, and checking when they were less confident about the future or anticipated a short term need for cash. On the second point, it was true that as people got older, they prudently put more money in safe accounts. Retired people in particular were encouraged to keep five years of anticipated withdrawals in a safe place, not the stock market. The Federal Reserve tracked the amount of these safe money accounts, known as the M2 money supply. Occasionally, George would look at this amount as a percent of GDP. Over the past decade the percentage of M2 to GDP had been growing.

This could be a natural trend of an aging population but there was another metric that concerned George. Over the past thirty years, people were keeping twice the amount of money in safe accounts. In the early 1980s, it had been about $8000. After accounting for inflation over the past thirty years, the per capita average was $15000.

George guessed that this cautious move to safety would contribute to slowing economic growth for years to come. But he wouldn’t tell Mabel that. He was also keeping a wary eye on small cap stocks.

If the index continued to break down below the neckline, George expected further weakness, perhaps another 10% drop as investors lost confidence in small cap stocks. Falling oil prices and low gas prices helped small caps but the strong dollar and continued weakness in the European countries and Japan would curtail export growth.

Armed with a mental outline of his presentation, George sat down next to Mabel in the living room. “Whatcha reading?” he asked. If she was in the middle of a whodunit, this wouldn’t be a good time. “It’s a series of papers, mostly statistical studies on student scores,” she said. “Teaching models, and correlations with their socioeconomic backgrounds, their race. Lorraine lent me her copy. It’s very interesting but reminds me that I need to brush up on some terms.”

This was good, George thought. Her brain was in analytical mode already. “Hey, hon, I wanted to talk to you about that CD coming up next week,” he started. “Oh, yeh,” Mabel responded. “I was at the bank the other day and couldn’t believe how low the rates are now. Why do they insult their customers by posting the rates?” she mused.

“I was thinking about that,” George stepped in. God, she was making this easy, he thought. “What do you think,” she continued, “maybe move that money into one of those bond index funds?” she asked. “Uh, yeh,” George said, a bit befuddled. She was making it too easy after all the time he’d spent planning his presentation, her objections, and his persuasive responses. “You had said you wanted to keep everything totally safe, so I thought…,” George’s voice trailed off. “Well, I do, but this is ridiculous,” Mabel said. “Obviously, we are going to have to take some risk.” “And I’ve got the time to watch it,” George reassured her. “I’ve noticed that,” she said. “I don’t have the interest to watch it. I guess I always thought that investing was a ‘set it and forget it’ proposition. Maybe it was never that way. But, after 2008, I’m…” and she gave a rock-the-boat gesture with her hand. “Ok,” George said and stood up. “I’ll have the bank close out the CD, then transfer the money.”