May 18, 2025

By Stephen Stofka

This is part of a series on persistent problems. The conversations are voiced by Abel, a Wilsonian with a faith that government can ameliorate social and economic injustices to improve society’s welfare, and Cain, who believes that individual autonomy, the free market and the price system promote the greatest good.

Abel scooped some egg on his waffle. “We’ve talked about the many responsibilities that schools carry and then I was reading a BBC article about clinics in Britain that treat severely obese kids. Since they started these clinics in 2021, they’ve treated almost 5000 kids (Source).”

Cain interrupted. “How many kids are in school over there?”

Abel replied, “Almost 8 million (Source). So this is a small percentage of the school population, but these are the kids referred by their family or school physician. The problem is probably a lot bigger.”

Cain glanced up from his coffee cup. “I always think of obesity as an American problem. I wonder how Britain compares to the U.S.?”

Abel nodded. “A few years back, New York City estimated that over 6% of K-8 kids were severely obese, but they use a slightly different methodology than Britain to classify kids (Source).”

Cain interrupted. “You mean if I walk into a New York City classroom of 16 students, one of them will be severely or morbidly obese?”

Abel shrugged. “They might not even be there. A lot more absences among those kids. They struggle academically.”

Cain frowned. “I expect more obese kids in towns that are car dependent. I always figured New York kids would walk a lot. Anyhow, how do they determine severely obese?”

Abel replied, “Britain uses a BMI over 40. They’ve been referred by a doctor. Some kids have BMIs over 50, like morbidly obese. Thirty percent of the kids who come to the clinics already showed signs of liver disease.”

Cain raised his eyebrows. “Liver disease at that age? Oh, wow. Did they say what the problem was? Does Britain have a program where poor kids get free lunches? Are the schools feeding these kids too much junk food?”

Abel glanced at his phone. “Hold on. I took notes. So, 40% of them came from poor neighborhoods and the schools in Britain do provide free meals for disadvantaged children. FSM they call it. Free school meals.”

Cain asked, “So how many school kids, fat or not, come from disadvantaged homes?”

Abel glanced at his phone again. “Yeah, what’s the baseline? Twenty-seven percent of all kids qualify for the free meal program (Source), but 40% of the severely obese come from disadvantaged neighborhoods. So, that’s a disproportionate amount of severe obesity among poor kids in Britain. New York City found that the percent of children with severe obesity has stayed about the same among all school kids during the past decade, but it has grown among minority students.”

Cain frowned. “My first instinct is to put some blame on the schools for the crap they serve in the cafeteria.”

Abel laughed. “Well, kids are not terribly fond of fruit and veggies. You can’t blame the cafeteria for that.”

Cain was equivocal. “Yeah, but all the white bread, the corn oil, the hot dogs and other prepared foods.”

Abel shook his head. “The kids who come from higher income homes are eating in the cafeteria as well. The only difference is their parents have to pay for it. If the school cafeteria were the chief culprit, there would a growing effect among the whole school population, not just minorities. Overall, though, that report showed a general decline among the entire student population during that decade. Obesity among disadvantaged students ran counter to the trend. So, what’s your next theory, Mr. Einstein?”

Cain smiled. “Hey, I’m improvising. How do they fatten up cattle? Feed them corn. Since the 1960s, we’ve been eating more processed food, more take-out food. What do those foods use? A lot of corn oil. It’s got a neutral flavor and a high smoke point. Great for deep fat fries. Too many Americans eat like it’s the state fair in July. Pass the grease, please.”

Abel argued, “That explains a growing obesity in the general population, but it doesn’t explain why obesity is growing even faster in disadvantaged communities, particularly among minority populations. A lot of those communities are food deserts. The big grocery store chains have moved out. The independent grocery chains struggle because they cannot get competitive pricing from their distributors. What’s left? Convenience stores. Packaged foods. Fried foods, ready to eat.”

Cain smiled. “Like the school cafeteria. Can families use food stamps for hot dogs at the convenience store?”

Abel shook his head. “Nope. Food stamps, or SNAP benefits, can’t be used for ready-to-eat meals.”

Cain argued, “But families can pay for a ready-to-eat hot dog and get a bottled soda with food stamps. Sugar, salt, and mystery meat with a bunch of chemicals, all in one convenient package, aided by taxpayer dollars.”

Abel frowned. “The amount a person gets on the SNAP program is relatively small, a bit over $6 a day (Source). RFK Jr. and his buddies want to ban the purchases of soda or candy with food stamps (Source).”

Cain scoffed. “Money is fungible. Like I said, they’ll just pay for the candy and use food stamps for something else. As we discussed last week, we’ve got an activist court. Now we’ve got an activist executive branch and an impotent Congress.”

Abel smirked. “This is who you voted for.”

Cain laid his hands in his lap. “What I voted for was what I thought was the better of two bad choices. Gallup reported that Biden and Trump have the two lowest average poll ratings in the modern era (Source).”

Abel asked, “Can I guess who has the lowest? Trump?”

Cain smiled. “Yeah. I was surprised. I thought it would be Bush and Trump. Bush had the worst Presidency, in my opinion. He kicked away a budget surplus, lied to the American people…”

Abel interrupted. “Lied to themselves as well. Johnson lied about Vietnam, but he knew he was lying. He’d only been in office a few months after Kennedy was shot and he thought Vietnam was going to be a boondoggle. He was worried that people would say he was weak, that he was an accidental president (Source).”

Cain nodded. “He lied to Congress about the incident in the Gulf of Tonkin to get authorization for an undeclared war (Source). Did the Democratic House impeach him? No. Nixon lies about Watergate and the Democrats impeach him. Noble principles? That’s the lie they tell themselves and the public to cover up the viciousness, deceit and self-dealing that is at the heart of everyday politics.”

Abel replied, “I hate when you get so cynical.”

Cain shook his head. “It’s realism, not cynicism. Look, politics brings out the worst in people. We see it at City Council meetings, in state legislatures, in the White House and Congress. Lions and hyenas fight over a kill. It’s visible. People fight over invisible things like power and principles, but the carnage is just as ugly as a carcass on the African plain.”

Abel sighed. “So what’s your solution?”

Cain replied, “Make as few rules as possible. The smaller the carcass, the less incentive for politicians to fight over.”

Abel nodded. “Incentives. I was reading a book this week called “Hell To Pay” by Michael Lind. He writes about all the ways that companies suppress workers’ bargaining power. Non-compete clauses, legal and illegal immigration, salary bands.”

Cain asked, “What are salary bands?”

Abel replied, “It’s a way that companies in a sector can collude on wage levels.”

Cain interjected, “Price fixing, in other words.”

Abel nodded. “Yeah. It’s illegal so companies hire a third party HR consultant that tells them what other companies in that sector and area are paying.”

Cain smiled. “Regulatory compliance is a game of cat and mouse.”

Abel continued, “Lind recommends allowing collective bargaining by sector for some industries. Railroads and airlines do it. For small businesses, he suggests a regional or local wage board that would set wages and working conditions.”

Cain looked doubtful. “Let me make this more concrete. Instead of Amazon workers at one facility bargaining for wage increases, all warehouse workers in the entire country would bargain collectively with all employers in warehousing. So all the pay structures are the same throughout an industry?”

Abel nodded. “I suppose so.”

Cain asked, “But there are both large and small employers in the warehouse sector. Are small businesses and their workers subject to a wage board or are they included in the collective bargaining with Amazon and its employees?”

Abel lifted his shoulders. “I have no idea. Lind didn’t get into those kind of details.”

Cain winced. “And if they can’t agree on wages or benefits? Do all warehouse workers go on strike? This scheme complicates contractual relationships.”

Abel replied, “I don’t know. He suggested an independent commission like the FCC that would oversee the whole process. I suppose it could step in and act as a final arbiter and prevent strikes.”

Cain asked, “Almost like a guild system, don’t you think? The merchant guilds protected the interests of shopkeepers and artisan guilds protected some workers in skilled trades, I think.”

Abel smiled. “I hadn’t made that connection. I thought you would like the idea because it allows private parties to resolve things. Lind suggested eliminating non-compete agreements as well. They disembowel workers as a prerequisite for employment. They should be illegal anyway.”

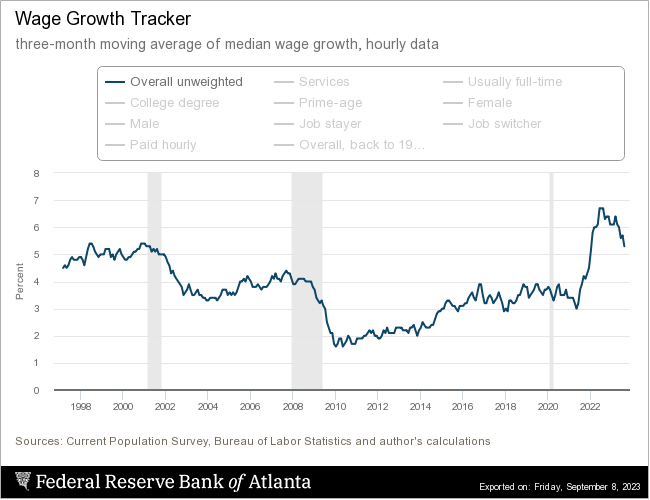

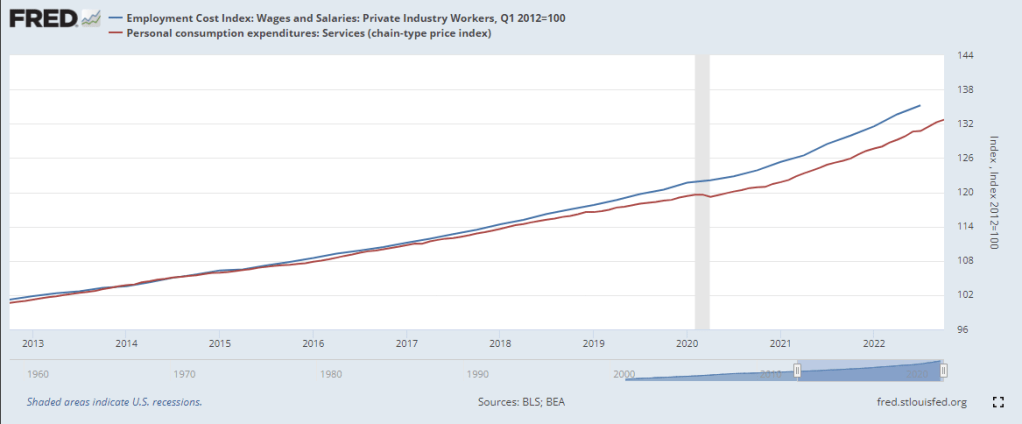

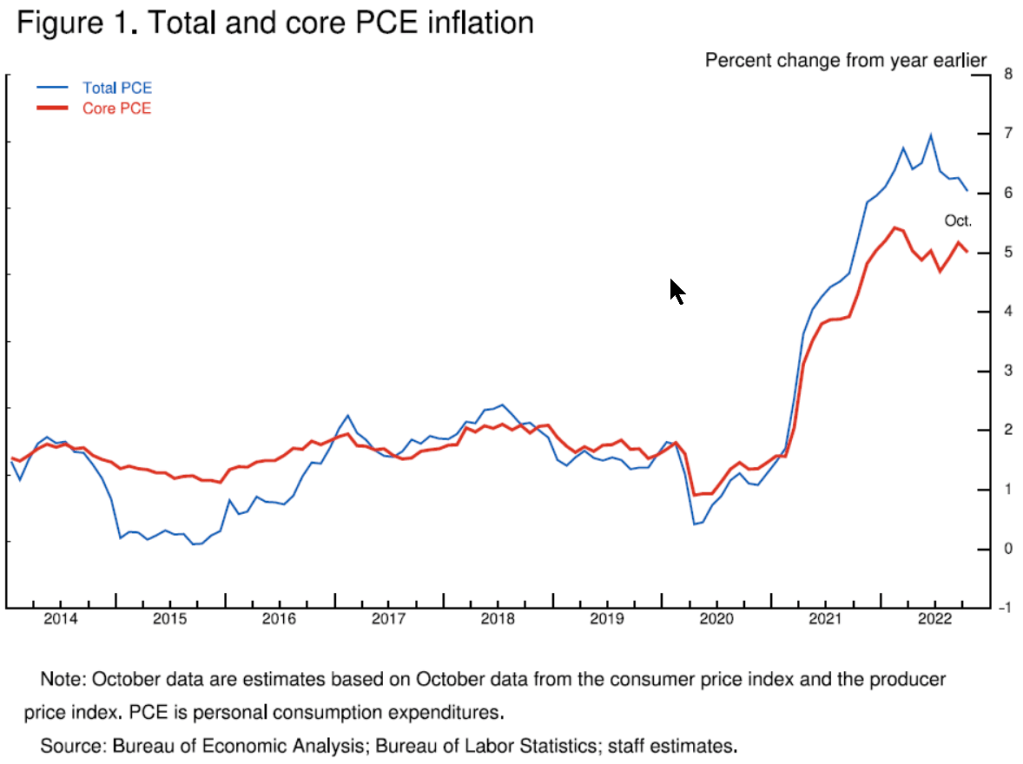

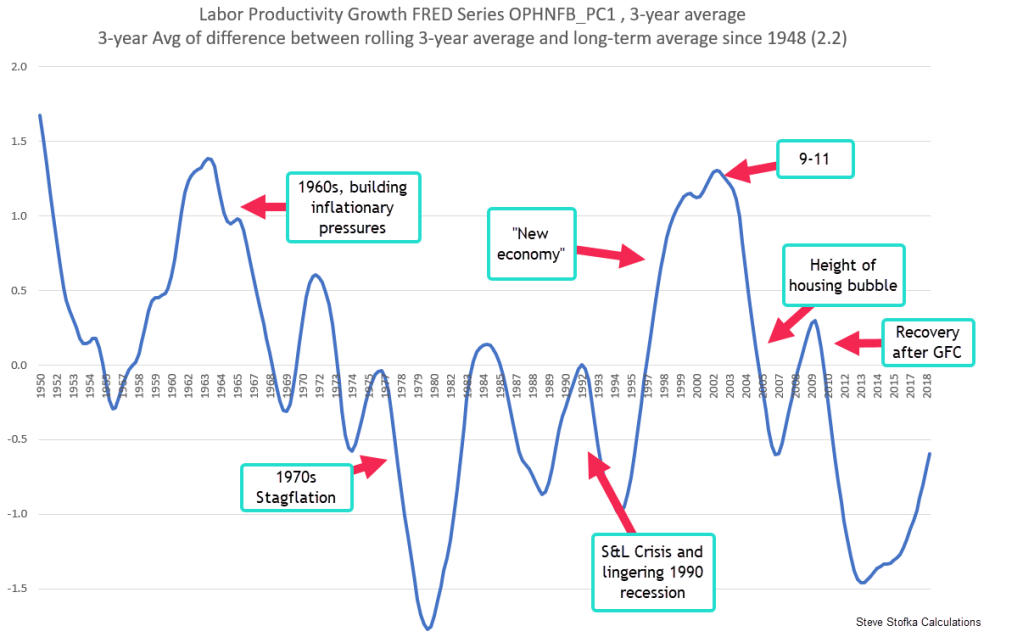

Cain replied, “You’re basically for any regulation that will give workers more pricing power. Companies markup any increase in wages, so workers might make more money, but everyone will be paying higher prices. In response to rising prices, the Fed will raise interest rates. That will make homes and cars less affordable because of the higher loan payments.”

Abel interrupted, “People will be less dependent on government charity. They will eat better. They will live longer. There is a strong correlation between life expectancy and per capita personal income in each state.”

Cain asked, “Will they? Higher rates means less investment growth, fewer jobs added, maybe some job losses. Some workers are making more money, some people are out of jobs, and everyone is paying higher prices. It’s not so simple.”

Abel argued, “The existing system is demeaning for some people. Wal-Mart employees often don’t make enough to provide for their families. They rely on various government programs to supplement their income (Source). That is an indirect subsidy from the government to Wal-Mart. That subsidy goes into the pockets of the Walton family that owns almost half of the stock (Source). If Wal-Mart employees belonged to a retail union, their representatives would be bargaining with Wal-Mart and Kroger and Target and Home Depot.”

Cain shook his head. “It’s too big, too broad. A person with plumbing knowledge working in Home Depot is going to paid the same amount as someone scanning groceries in a checkout lane?”

Abel argued, “Obviously, there would be different classifications of retail employees. However, a plumbing guy working in Home Depot for a certain number of years would get paid the same as a plumbing guy in Ace Hardware or Lowe’s.”

Cain asked, “Who is going to mandate these classifications?”

Abel replied, “No mandates. The stores and employee union will probably agree on some distinctions. They can resolve that in negotiations, I suppose.”

Cain asked, “What about small businesses? Would employees get the same pay and benefits as large businesses? If so, a company like Home Depot would be able to offer employees health care at a lower cost than small businesses. Would there be a law mandating that a small business get the same insurance rates as a big company? What about different living standards in different states? There would have to be an adjustment for that.”

Abel rolled his eyes. “Questions I can’t answer. I don’t know. The private sector would have to work that out. I thought you liked that.”

Cain nodded. “Benefits complicate any solutions. They introduce factors that are outside of the industrial sector that a company operates in. Health insurance, for one. Retirement plans involve the financial industry, also a different sector. Mandated taxes like Social Security and Unemployment insurance involve other government programs. The politicians will be eager to meddle.”

Abel replied, “Ok, so what if there were no benefit package for employees? Start there.”

Cain said, “In 1960, Ronald Coase wrote The Problem of Social Cost (Source). He pointed out that when government imposes a regulation on a firm, the government acts as a super-firm in the sense that it controls a factor of production for each firm subject to the regulation.”

Abel interrupted, “What? That’s like saying that the umpire is a super-team. The government is just there to make sure everyone plays by the rules.”

Cain smirked. “Umpires don’t write the rules. Coase’s point was that private firms must make production decisions within the constraints of the market. They have to adjust to changing market conditions. A government agency has no such constraints. Laws and regulations do not respond to changing conditions. That’s why I favor as few government rules as possible.”

Abel sighed. “Well, we can’t live in an ideal world. I thought this was a realistic solution. I liked the empowerment of workers. Lind gave a lot of examples of how businesses weaken the power of workers to command a living wage. Temporary work visas, for one.”

Cain nodded. “What a racket that is. People with highly specialized skills and there are no American workers to fill the positions? The software company pays visa holders relatively low wages for all these specialized skills. Why is that? Oh, and that knowledgeable visa holder needs to be trained by the same person they will replace. It’s a scam.”

Abel laughed. “You’re familiar with some of the things that Lind talks about in the book. He also mentions the fact that most of those H-1b visas are given to workers from India. It’s almost three-quarters (Source). No other software engineers or computer scientists in the rest of the world? Only in India?”

Cain smirked. “A scam to cut costs by paying workers less. Another persistent problem in Washington is illegal immigration. It increases the labor supply and lowers wages, which benefits employers.”

Abel interrupted, “More demand for housing which increases housing costs and hurts workers. Lind writes about that too. So, if companies can combine to lobby for policies that enhance their power with workers, why can’t workers do the same?”

Cain shook his head. “I have so little faith in politicians to promote self-reliance. They need the public to depend on them. It gives them a sense of purpose and bargaining power.”

Abel argued, “Well, we need an alternative to the current system. Too many workers cannot earn a living wage and have to rely on government programs to get by. Growing obesity in kids from poor families is an indicator of a diseased system.”

Cain sighed. “Now comes the rant against capitalism?”

Abel smirked. “No, no rant. Lind mentions Adam Smith’s comment that a worker should have enough to maintain himself, and extra to raise his family and deal with emergencies. That’s not a recommendation from some socialist economist, but someone who advocated a minimum of regulations. Implementing sectoral bargaining for workers has the promise of lightening government’s role in the marketplace while correcting some of the abuses that our political system has enabled.”

Cain said, “The promise of a lighter role for government? This commission. Is it composed of political appointees?”

Abel shook his head. “Lind, the author, suggested an independent commission.”

Cain asked, “Like the Fed?”

Abel nodded. “Lind gave the FCC as an example, I think, but the idea is the same. I prefer a model along the lines of the Fed, I think. Staggered terms that are longer than four years, so the members of the commission are less subject to the political whims of one party.”

Cain argued, “That’s too much power concentrated in one commission.”

Abel replied, “Look how much power the Fed has. For more than a hundred years, it has given our economy more stability than in the hundred years before the Fed. That stableness attracts capital from the rest of the world.”

Cain looked doubtful. “Talking about the Fed. As I said before, higher incomes will lead to higher prices, higher interest rates. It’s something we could talk about at another time. You said life expectancy had a strong correlation with income. What’s strong?”

Abel replied, “.85. That was based on 2021 figures.”

Cain looked thoughtful. “I wonder what the correlation is in Canada or Britain. I want to check on that. Maybe read that book. Hey, I need to get going. An interesting discussion this week. ”

Abel nodded. “Yeah. See you next week.”

////////////////////

Image by ChatGPT.