August 27, 2017

Pew Research surveyed four generations of Americans, from the oldest Americans who are part of the Silent Generation, those who grew up during the Great Depression, to the Millennials, those born between the years 1983 – 2002. Pew asked the respondents to list ten events (not their own) or trends that happened during their lifetime that had the most influence on the country. 9-11 was at the top of the list for all four generations. Obama’s election, the tech revolution and the Iraq/Afghanistan war were the other events common on each list. Some differences among the generations were understandable. Some were a surprise to me. The Great Recession/Financial Crisis of 2008 was only on the Millennials list. Many in this generation were in the early stages of their careers when the recession began. Here is a link to the survey results. Perhaps you would like to make your own list. Keep in mind that the events must have happened during your lifetime.

I don’t think that the Boomer generation understands the long-term impact of the Great Recession. In another decade, many will discover how vulnerable the financial crisis left all of us, not just the Millennials. As we’ll see below, the crisis may be over but the response to the crisis is ongoing.

One of the trends common to each generation’s list was the tech revolution, which has reshaped much of the economy just as the last tech revolution did in the 1920s. The widespread use of electricity, radio and telephone in that decade transformed almost every sector of the economy and accelerated the mass migration of the labor force from the farm to the city.

Like today, a small number of people made great fortunes. Like today, the top 1% of incomes accounted for about 15% of all income (Saez, Piketty). The GINI index, a statistical measure of inequality of any data set, has risen significantly since 1967 (Federal Reserve). The GINI index ranges from 0, perfect equality, to 1, perfect inequality. Incomes in the U.S. are more equal than South Africa, Columbia and Haiti (Wikipedia) but we are last among developed countries.

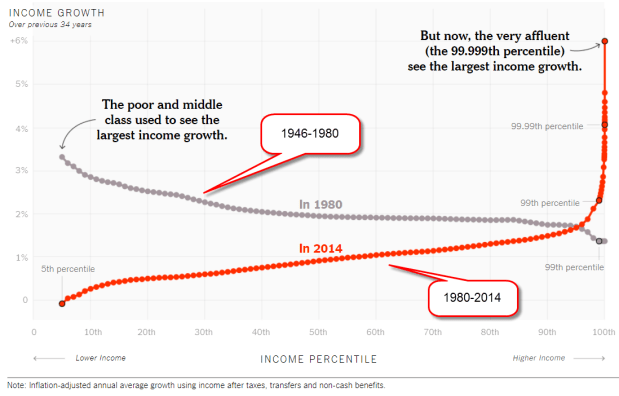

For several decades, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez have collected the aggregate income and tax data of developed countries. Piketty is the author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Capital), which I reviewed here. A recent NY Times article referenced a report from Piketty and Saez comparing the growth of after-tax, inflation-adjusted incomes from 1946-1980 (gray line labeled 1980) and 1980-2014 (red line labeled 2014). I’ve marked up their graph a bit.

The authors calculated net incomes after taxes and transfers to determine the effect of tax and social policies on income distribution. Transfers include social welfare programs like Social Security, TANF, and unemployment. Census Bureau surveys of household income include pre-tax income and it is these surveys which form the basis for the calculation of the GINI index and other statistical measures of inequality.

I am guessing that Piketty and Saez used their database of IRS post-tax income data then adjusted for transfer income based on Census Bureau surveys. The Census Bureau notes that people underreport their incomes on these surveys. Is the IRS data more reliable? Probably, but people do hide income from the IRS. Both Piketty and the Census Bureau note that the data does not capture non-cash benefits like food stamps, housing subsidies, etc.

From 1947 to the early 1960s, the very rich paid income tax rates of 90% so that would seem to explain the after-tax income data from Piketty and Saez. The federal government took a lot of money from the very rich, paid off war debts, built highways, flew to the moon and built a big defense network to fight the Cold War. Those infrastructure projects employed the working class at a wage that lifted them into the middle class. So that should be the end of the story. High taxes on the rich led to more equality of after-tax income.

But that doesn’t explain the pre-tax income data from the Census Bureau. The very rich simply made less money or they learned how to hide it because of the extremely high tax rates. In the Bahamas and Caymans, there grew a powerful financial industry devoted to hiding income and wealth from the taxman. In the first years of his administration, President Kennedy, a Democrat, understood that the extremely high tax rates were hurting investment, incentives and economic growth. He proposed lowering both individual and corporate rates but could not get his proposal through the Congress before he died. Johnson did push it through a few months after Kennedy’s death. The rate on the top incomes fell from 91% to 70%, still rather high by today’s standards.

An important component of income growth in the post war period from 1947-1970 was the lack of competition from other developed countries who had to rebuild their industries following World War 2. These two decades were the first when the government began collecting a lot of data, and this unusual period then became the base for many political arguments. Liberal politicians like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren advocate policies that they promise will return us to the trends of that period. It is unlikely that any policies, no matter how dramatic, could accomplish that because the rest of the world is no longer recovering from a World War.

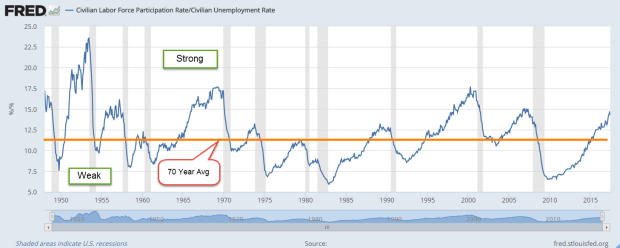

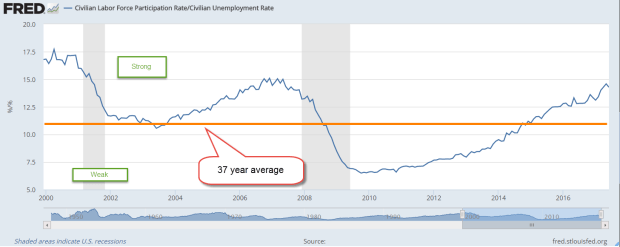

We could enact a network of social support policies that resemble those in Europe but could we get used to a 10% unemployment rate that is customary in France? For thirty years beginning in the early 1980s, even Germany, the powerhouse of the Eurozone, had an unemployment rate that exceeded 8%. At that rate, many Americans think the economy is broken. Despite 17 quarters of growth, unemployment in the Eurozone is still 9.1%. Half of unemployed workers in the Eurozone have been unemployed for more than a year. In America, that rate of long term unemployed is only 13% (WSJ paywall).

The post-war period was marked by high tax rates and high federal spending, a period of robust government fiscal policy. The federal government intervenes in the economy via a second channel – the monetary policy conducted by the central bank. The Federal Reserve lowers and raises interest rates, and adjusts the effective money supply by the purchase or sale of Treasury debt.

The 1940s, 1970s and 2000s were periods of high intervention in both fiscal and monetary policy. The FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, Johnson and Nixon administrations exerted much pressure on the Fed to help finance war campaigns and the Cold War. In 1977, the Congress ensured more independence to the Federal Reserve by setting two, and only two, clear objectives that were to guide the Fed’s monetary policy in the future: healthy employment and stable inflation.

A rough guide to the level of central bank intervention is the interest rate set by the Fed. When rates are less than inflation, the Fed is probably doing too much in response to some acute or protracted crisis.

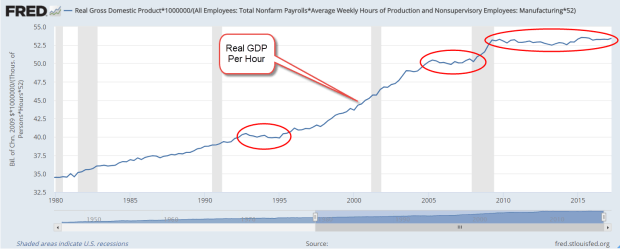

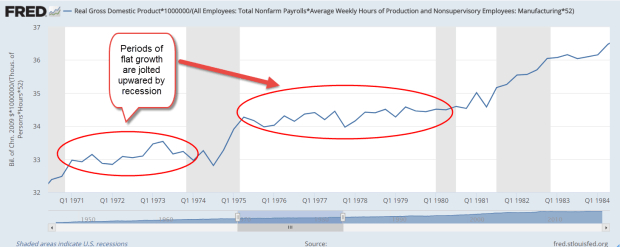

Let’s look at an odd – or not – coincidence. I’ll turn to the total return from stocks to understand the effects of central bank policies. There are two components to total return: 1) price appreciation, and 2) dividends. When price appreciation is more than 50% of total return, economic growth and company profits are doing well. Future profit growth looks good and more money comes into the market and drives up prices. When dividends account for more than half of total return, as it did in the 1940s and 1970s, both GDP and company profit growth are weak. Both decades were marked by heavy central bank and government intervention in the economy.

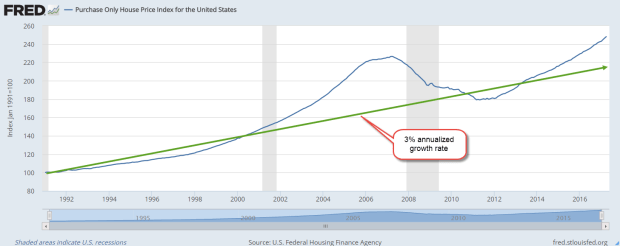

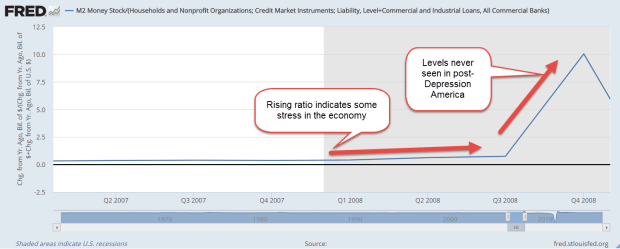

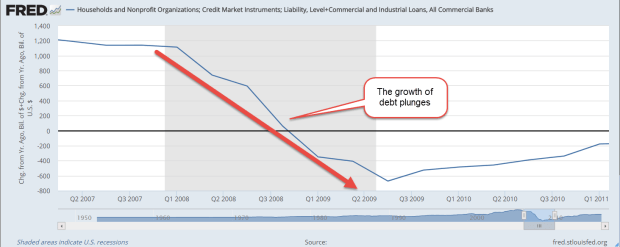

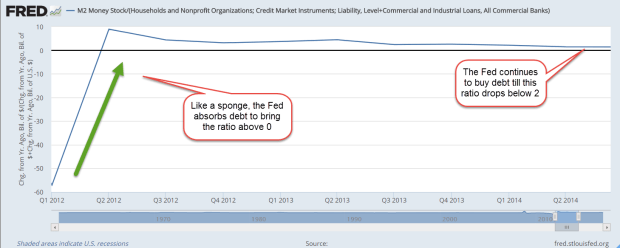

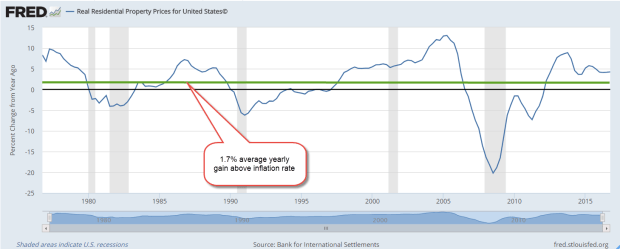

Here’s a link to an article showing the total return on stocks by decade. During the 2000s, the total return from stocks was below zero. An average annual return of 1.5% from dividends could not offset an annual loss of 2.4% in price appreciation. Hubris and political pressure following 9-11 led Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan to make several ill-advised interest-rate moves in the early 2000s that helped fuel the housing boom and the ensuing financial crisis. His successor, Ben Bernanke, continued the policy of heavy intervention. Following the financial crisis, the Fed kept interest rates near zero for nine years and has only recently begun a program of gradually increasing its key interest rate.

The price gains of the 2010s have lifted the average annual return of the past 18 years to 7.4%, and the portion from dividends is exactly half of that, at 3.72% per year. It has taken extraordinary monetary policy to rescue investors, to achieve balanced returns that are about average from our stock investments. Some investors are betting that the Fed will always come to the rescue of asset prices. That same gamble pushed the country to the financial crisis when the government did not rescue Lehman Brothers in September 2008.

The financial crisis should have been on each generation’s list. Within ten years it will be. It is still crouched in the tall grass.

///////////////////////////

Debt

Happy days are here again. Yes, girls and boys, it’s time to raise the debt ceiling! By the end of September, the Treasury will run out of money to pay bills unless the debt ceiling is raised. This past week, President Trump hinted/threatened that he would not sign a debt increase bill unless it included money to build the wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

The Congress has not had a budget agreement in several years and is unlikely to enact one this year. People may sound tough on debt but a Pew Research study

showed that a majority do not want to cut government programs, including Medicaid.

Liberal economists insist that government debt levels don’t matter if the interest on the debt can be paid. This article from Pew Research shows the historically low rate on the federal debt. However, Moody’s reports that the U.S. government pays the highest interest as a percentage of revenue among developed countries. As a percent of GDP, we are 4th at 2.5%.