July 26, 2015

Each year, the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) submits the Economic Report of the President to the Congress. They compile a number of data series to show some long term trends in household income, wages, productivity and labor participation. Readers should understand that the report, coming from a committee acting under a Democratic President, filters the data to express a political point of view that is skewed to the left. When the President is from the Republican Party, the filters express a conservative viewpoint. Has there ever been a neutral economic viewpoint?

In this year’s report the Council identifies three distinct periods since the end of WW2: 1948-1973, 1973-1995, and 1995-2013. In hindsight, this last period may not be a single bloc, as the report acknowledges (p. 32).

The most common measure of productivity growth is Labor Productivity, which is the increase in output divided by the number of hours to get that increase. Total Factor Productivity, sometimes called Multi-Factor Productivity (BLS page), measures all inputs to production – labor, material, and capital. As we can see in the chart below (page source), total factor productivity has declined substantially since the two decade period following WW2.

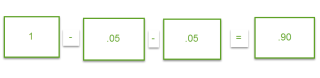

In the first period 1948-1973, average household income grew at a rate that was 50% greater than total productivity growth, an unsustainable situation. This post war period, when the factories of Europe had been destroyed and America was the workshop of the world, may have been a singular time never to be repeated. What can’t go on forever, won’t. In the period 1973-1995, real median household income that included employer benefits grew by .4% per year, the same growth rate as total productivity.

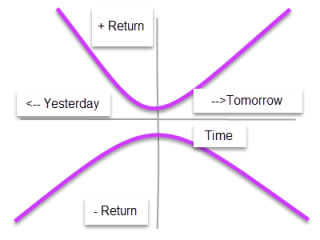

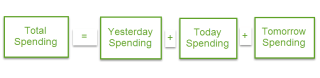

The decline in the growth rate of productivity hinders income growth which prompts voters to pressure politicians to “fix” the slower wage growth. If households enjoyed almost 3% income growth in the 1950s and 1960s, they want the same in subsequent decades. If the rest of the world has become more competitive, voters don’t care. “Fix it,” they – er, we – tell politicians, who craft social benefit programs and tax programs which shift income gains so that households can once again enjoy an unsustainable situation: income growth that is greater than total productivity growth.

“Where Have All The Flowers Gone?” was a song written by legendary folk singer Pete Seeger in the 1950s. It was a song about the folly of war but the sentiment applies just as well to politicians who think that they can overcome some of the fundamental forces of economics. Seeger asked: “When will they ever learn?”