June 1st, 2014

First a shout out to our friends in the southern hemisphere where the winter is beginning in earnest. Hey, you had the sun for six months. Now it’s our turn. We all have to share. I think that because there are more people in the northern hemisphere, the sun should stay up here for longer than six months. It’s not fair.

Piketty Controversy

Talking about fair…..Last week I touched on some of the highlights in Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the 21st Century. At the time of that writing, Chris Giles in the Financial Times had just reported that he found some data errors while using Piketty’s source material. Giles’ criticisms were rather precise and included charts of the revised data which Giles claimed contradicted Piketty’s conclusions that wealth inequality had risen during the past thirty years. This past Friday, the financial site Bloomberg reported that Piketty had rebutted criticisms of his methodology. En garde!!! For those of you who are not interested in the minutiae of the disagreements, I will quote from Piketty’s response:

What is troubling about the FT methodological choices is that they use the estimates based upon estate tax statistics for the older decades (until the 1980s), and then they shift to the survey based estimates for the more recent period. This is problematic because we know that in every country wealth surveys tend to underestimate top wealth shares as compared to estimates based upon administrative fiscal data. Therefore such a methodological choice is bound to bias the results in the direction of declining inequality.

Piketty’s rebuttal is sound but the debate over data and methodology does underscore a problem. There were times when I have questioned Piketty’s data only to find that he addressed those concerns in either the footnotes to the book or in notes contained in his tables. Fearing that I might put readers to sleep, I edited out of last week’s blog a concern I had with Piketty’s rate of inflation shown on page 448 when he presented a table – Table 12.2 – of historical returns by university endowments. Piketty states a 2.4% inflation rate from 1980-2010, which struck me as too low (BLS figures are 3.3%). In a note at the bottom of the Excel file TS12.2, he revealed that he used the GDP deflator, not the CPI, in order to keep data consistent with the GDP series. He could have stated this simply at the bottom of the table in the book. It’s not like the publishers were trying to save space in a 700 page book.

So, Open Letter to Professor Piketty and other Economists: Please put your caveats and clarifications up front and center and repeat often. Last week, I gave several examples of Piketty’s clarifications which could be found in a referenced paper or on one of the spreadsheets that his team compiled. James Joyce famously said of his book Finnegan’s Wake that he expected the reader to put as much time and effort in reading the book as Joyce did in writing the book. Relatively few people have read Finnegan’s Wake. Help us understand your point!!

For those of you who want more of the controversy, a reader sent me this, including Simon Wren-Lewis’s comments on the matter at Mainly Macro, which I link to every week on the side of this blog. Economist Tyler Cowen comments echo my concerns with valuations of capital that vary widely because of asset pricing. When an asset is difficult to price or varies widely in price, should one use the SNA international convention (System of National Accounts) and estimate a present value based on projected future flows? The founder of Vanguard, John Bogle, recommends this common sense approach for our personal portfolios; that we should stop looking at our statements and look at the money flows that our portfolio mix will probably generate them when we need them. That is the true worth of our portfolios, according to Bogle – not some temporary valuation based on the market prices on the last day of the month.

**************************

What is Income?

This week, as I listened to and read discussions of income in the U.S., it became apparent that there are understandable misconceptions of what is being counted when economists tally up the income of a household and the income of a nation. Update: Corrected. A 2011 report from the Census Bureau states that household income does include cash benefits before taxes. EITC payments are not included because they are a reverse tax (Source). Non-cash benefits like Medicaid, Food Stamps and housing assistance are not included. These non-cash benefits can easily surpass $1000 per month.

Money income includes earnings, unemployment compensation, workers’ compensation, Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, public assistance, veterans’ payments, survivor benefits, pension or retirement income, interest, dividends, rents, royalties, income from estates and trusts, educational assistance, alimony, child support, cash assistance from outside the household, and other miscellaneous sources.

The national income figures that Thomas Piketty uses in his book do include government transfers. The 2005 NIPA Guide summarizes what is included in personal income. IVA and CCAdj are inventory and depreciation adjustments.

Personal income is the sum of compensation of employees, received;

proprietors’ income with IVA and CCAdj;

rental income of persons with CCAdj;

personal income receipts on assets;

and personal current transfer receipts;

less contributions for government social insurance

Measuring income to determine an aggregate level of well-being within the population is challenging and gives each side ample ammunition in the political debate. The inclusion and exclusion of various types of benefit, cash and otherwise, leads one side to dismiss the conclusions of the other side and hinders a constructive dialog.

*************************

GDP Growth

Each month the BEA (Bureau of Economic Analysis) releases a new estimate of the previous quarter’s GDP. This past week the BEA released the 2nd estimate of 1st Quarter GDP growth, showing an annualized 1% decline. This was pretty much in line with consensus estimates and the market’s response was rather neutral on the day of the release. Much of the downturn was ascribed to the particularly harsh winter weather and many economists are projecting a 4% annualized increase in this quarter, a rebound to offset the past quarter’s decline.

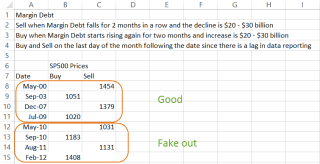

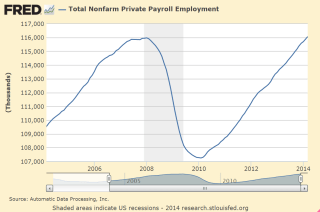

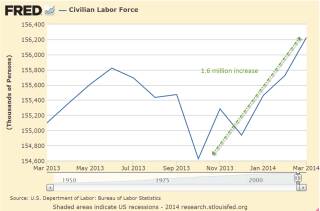

Peering under the hood of the GDP report: under the category of Private Domestic Investment, residential housing dropped almost 8% (annual rate) in the fourth quarter and another 5% in the first quarter of 2014. What is more surprising is the almost 2% drop in business investment. Let me go back to a paper by Ed Leamer that I first wrote about in February. Mr. Leamer’s thesis is that the sales of new homes first decreases, followed by a decrease in business investment. He found that this 1-2 punch precedes most recessions by about 3 – 4 quarters. In two cases, it was a false positive. Perhaps this latest 1-2 punch is a false positive. Perhaps it was just the winter weather. This economy does not feel like a recession is at all imminent. Industrial activity, the labor market and auto sales are strong or expanding. More perplexing to a casual investor might be a summer lurch downward in the market if the economy does not show signs of a correcting rebound.

*********************

Fixed Capital Consumption

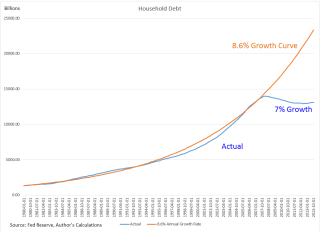

Since 2000, there has been a notable change in economic growth. It is not often that we see growth above 3% as we did in the 20th century.

Helping that meager growth rate look – well, less meager – is an item that the BEA adds to GDP called Fixed Capital Consumption. To the ordinary Joe, this is simply depreciation, but this is not the depreciation that your accountant might have mentioned if you own a small business or rent out part of your home. The depreciation that the BEA calculates is based on the current market price of a piece of equipment, for example, not the actual cost of the item. As an example, let’s say that Billy and Betty Jones bought a new $20,000 truck for their business and their accountant depreciates it over a 5-year cycle. To keep it simple, assume that the truck’s depreciation each year is 20%. That depreciation is based on the cost of the vehicle. Let’s do it the way the BEA does it (if only! The IRS does not allow this!). In year 3, the current market price of a similar vehicle is $24,000. 20% of $24,000 is $4800, higher than the $4000 depreciation based on the cost of the vehicle. In a given year, the amount of depreciation actually reported by companies might be $2 trillion. The BEA figure will be higher and this is included in Gross Domestic Product. As a percentage of GDP, depreciation has risen considerably since the early 2000s, driving up reported GDP growth just a smidge. Below is a chart of the increasing percentage of GDP that is Fixed Capital Consumption. Almost one of every six dollars of GDP is being allocated to depreciation, a third higher than 1960 rates.

In a low inflation environment, the change in the market prices of equipment and land is muted. Are capital expenditures becoming obsolete at a faster pace? Over the past two decades, software and systems development has become an increasing share of non-residential investment. Rapid changes in technology may be one driver of the acceleration in depreciation. Wikipedia has a good article on the concept as it is reported in the national accounts.

*************************

Education

As I mentioned last week, I’ll look at a paper I read recently which had some rather startling conclusions. In a paper published in the World Economic Review earlier this year, economists James Galbraith and J. Travis Hale reviewed paycheck and IRS income data to identify state and national trends in income inequality during the past 40+ years. It comes as no surprise that there is inequality between sectors in the economy, a fact which Galbraith and Hale acknowledge. Their particular focus was the changes in inequality within and between sectors at the state and national levels.

There are two components to income inequality: 1) wage growth or the lack of it; and 2) employment growth or the lack of it within each sector. If a particular sector experiences a period of high growth in earnings but jobs decline in that sector, then the gains become more concentrated and inequality between sectors grows.

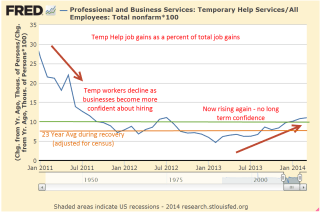

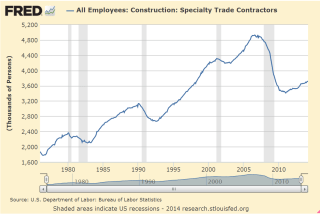

What Galbraith and Hale found was that the changes in the 1990s and 2000s had one common characteristic: booming sectors of the economy vs. non-booming sectors accounted for most of the growth in income inequality. Where each decade differed was the change in the sectors that experienced high growth. The 1990s was marked by a growth spike in information technology, giving rise to out-sized gains to workers in the professional, scientific, and technical fields. The 2000s was the decade of outsized growth in construction, defense and extractive technologies. Here is a troubling finding of their study: common to both periods is that the number of jobs declined in those sectors that experienced high wage growth. Higher pay = less job growth. Also common to both decades, until the financial crisis in 2008, was the high growth in the finance and insurance industries. Problem: Rising inequality. Remedy: More education. The authors acknowledge this common response:

When public discourse admits inequality to be a problem, education is often given as the cure. According to Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson (2006), for instance, the correct response to rising inequality is to “focus on helping people of all ages pursue first-rate education and retraining opportunities, so they can acquire the skills needed to advance in a competitive worldwide environment.” This is a view with powerful support among economists.

But their evidence casts this common conception into doubt:

As we’ve shown, the last two decades have seen significantly slower job growth in the high-earnings-growth sectors than in the economy at large. So even if large numbers of young people do “acquire the skills needed to advance” there is no evidence that the economy will provide them with jobs to suit. Many will simply end up not using their skills. Moreover, a strategy of investment in education presupposes advance knowledge of what the education should be for. Years of education in different fields are not perfect substitutes, and it does little good to train too many people for jobs that, in the short space of four or five years, may (and do) fall out of fashion. And experience shows clearly that the population does not know, in advance, what to train for. Rather, education and training have become a kind of lottery, whose winners and losers are determined, ex post, by the behavior of the economy.

Does this mean that parents and grandparents should cash in those college funds for the kids and take a long vacation with the money? Hardly. Bureau of Labor Statistics reveal that those with a college education have a significantly greater lifetime income than those without. The findings of this paper imply, however, that the economy and the job market change in ways which none of us can reliably predict. The wiser course for students might be the same advice financial advisors give to investors: diversify. If a student is majoring in philosophy, take some business, computer or science courses. Science majors could do with some literature and writing courses as well.

At the start of the 20th Century, 40% of the population was engaged in farming-related jobs. A century later, less than 2% of jobs are in the agricultural sector.

When I was a teenager, an aunt told me that a reliable bookkeeper could always find a job. That was before the introduction of the computer and accounting programs for small businesses.

The number of librarians has declined about 10% in less than a decade. In 1990, who could have predicted that?

Records Management, once a clerical job, has evolved into management of many interdependent mediums, complicated by laws and regulations that few could foresee just twenty years. A science major confident in the availability of work in a certain skilled profession might find that the introduction of a qubit computer in 2025 sharply reduces jobs in that profession.

*****************************

Takeaway

As investors, we often think that we can avoid the pain so many of us experienced in 2008 if we pay more attention to economic and corporate indicators. In hindsight, the graphed data looks so obvious. We ignore now what we didn’t ignore then because we know now what to ignore, making hindsight a marvel of clarity. The future enables us to filter out the noise of the past.

If China’s housing sector implodes and repercussions of that undermine the U.S. economy, we’ll criticize ourselves for not reading that article on page 24 that detailed the coming crisis. There will be a graph of some spread in interest rates or some other indicator that we glossed over at the time. If there is a recession 9 months from now (this is just an ‘if’), we will forget the harsh winter of 2014 that blinded us to the early warning signs. We will see the decline in 1st quarter GDP together with the decline in disposable personal income as the clearest of warning signs and slap ourselves on the head for missing it. Some guy will get on the telly and show us how he predicted it all along and we’ll think that we should get his newsletter because this guy knows.

As to our current disputes, the grandchildren of our grandchildren may be puzzled by our concerns with income and wealth inequality. We remember the first two paragraphs of the Declaration of Independence, which the signers largely agreed to with a few revisions. The majority of the Declaration is concerned with a list of grievances against the British Empire, which the signers debated vigorously, making numerous amendments to the text.

When did we last have a debate on which metal, gold or silver, should serve as a backing to the currency? This burning topic of the late 19th Century is of little more than historic interest.

Over a fifty year period in the 19th Century, bankruptcy became less a criminal act and more a civil matter, culminating in the Nelson Act in 1898 which codified our more modern notion of bankruptcy.

With relatively little debate, 19th Century Americans bequeathed their heirs a country dominated by large corporations. Less by design and more by default, the raising of private capital by corporations seemed to be a convenient solution to the persistent misuse of public funds by corrupt politicians in that century.

We no longer argue, as they did during the Civil War, whether the Federal Government has a responsibility to bury soldiers who have died on the battlefield.

We argue about guns and the meaning of the Second Amendment, which 19th Century Americans thought was non-controversial and not a universal individual right to gun ownership.

A hot topic of debate in the early part of the 20th Century was whether Irish, Italians and other Southern European immigrants were fully evolved humans and were capable of exercising the right to vote.

19th Century Americans argued about the moral validity of slavery. We don’t.

What is the minimum working age for children? Is it six or eight years of age? What should be the legal maximum hours that they can work? These burning questions of the early 20th Century are dead embers now.

The issues changes, our perspectives change, but we can be sure of one thing: in a hundred years, we will still be arguing as much as we do today and that is oddly reassuring.