April 22, 2018

by Steve Stofka

America is built on prejudice and the passionate denial that we are a country built on prejudice.

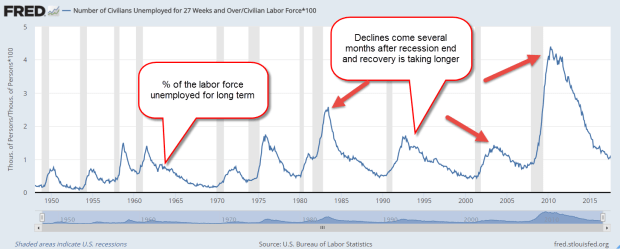

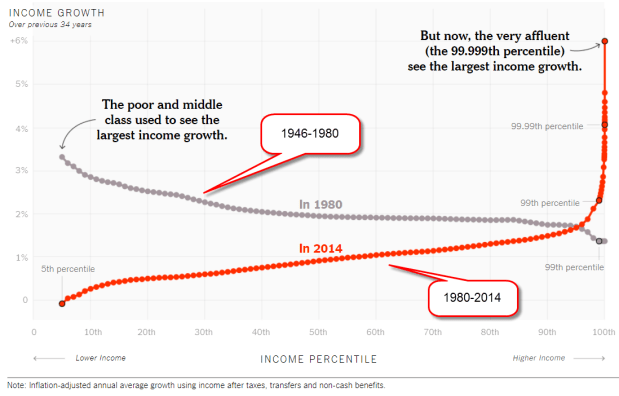

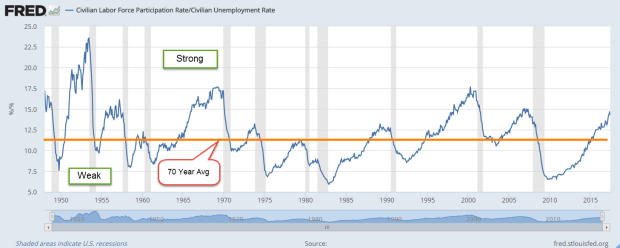

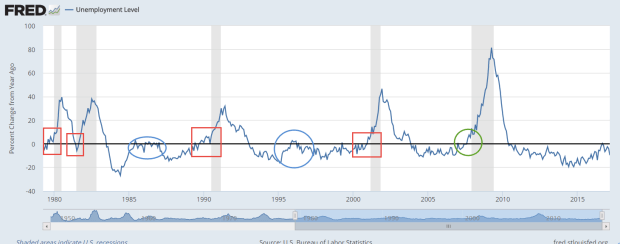

Investors who understand the role of prejudice in the economics of this society can recognize a few early signs of a coming recession. A strong economy, like a bull stock market, raises all boats, including those at the margins who are easily stranded. During the financial crisis, they were the first to be discarded. As the current strength of the economy is finally able to lift the fortunes of the more vulnerable, countervailing forces will undermine that strength.

From the country’s founding, broken and forced land treaties, enforced by superior military power, have sidelined those with red skin. Like the thoroughbred horses in the upcoming Kentucky Derby, Americans with black or brown skin must carry an extra weight during the race of life. I’ll show one data sign of this weight. White people must bear their own burden: privilege. Centuries of discrimination blocked those with black skin from many housing and job choices to give those with white skin a better chance at success. The prejudice against those with brown skin is less strong but has intensified when Candidate Trump used the issue of illegal immigration to taint those with brown skin or Hispanic surnames, regardless of their citizenship.

America has a shorter history of isolating and persecuting immigrants of white skin. First it was the Irish who immigrated to America after the potato blight devastated Ireland’s staple crop in the mid-19th century. Newspapers and periodicals portrayed the Irish as ignorant, shiftless criminals. In a country dominated by Republicans, many Irish were Catholic and suspected of being more loyal to the pope in Rome than democratically elected leaders in America.

As the century turned, Italians and southern Europeans became the target of American prejudice (History). Like the Irish, many Italians were Catholic and not to be trusted. To this day, no Italian has been elected President. JFK was the first successful Irish Catholic candidate for the Presidency, and he had to overcome objections that he would turn to the Pope for advice on national policy.

As discriminatory as Protestants have been to Catholics, they have been especially unkind to those of other Protestant sects. As more Catholics migrated to America, many Protestants in America deflected their prejudices from other Protestants to the Catholics as easy targets of discrimination.

In America, Jews encountered less discrimination than in Europe but housing, job and social discrimination were prevalent in the first half of the 20th Century. In the 19th Century, those of the Mormon faith were driven out of Ohio, then Missouri, and Illinois by Protestant sects who regarded Mormons as non-Christians. The abandoned farms and businesses were auctioned off to the Christian righteous who remained. Mormons escaped across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains to settle in a valley in Utah. Following the Holocaust during World War 2, there was a proposal to settle many European Jews in Utah, but Mormons nixed the idea. Even those who suffer persecution for their religious beliefs are not immune to bias.

From Europe, Protestant settlers brought their prejudices with them. Those Protestants who immigrated to America because of religious persecution were often fleeing long standing animosities with other Protestant sects. Eight of the thirteen colonies established churches of a particular denomination and only those citizens belonging to that denomination were allowed to hold office. Each Protestant sect was convinced that the other sects had strayed from the message and meaning of the Bible. To counter such discrimination, Virginia adopted an amendment to protect religious freedom even before the founding of the United States. Mindful of these bedrock prejudices, the Founding Fathers based the language of the First Amendment on the laws of several states protecting religious freedom.

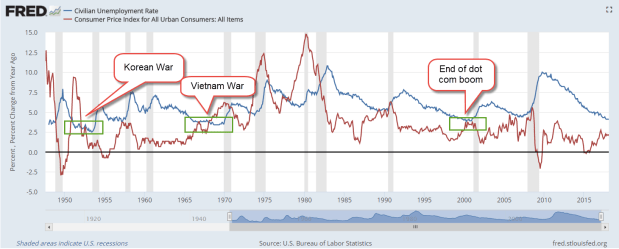

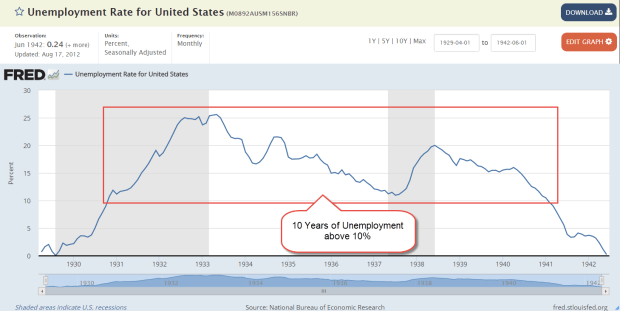

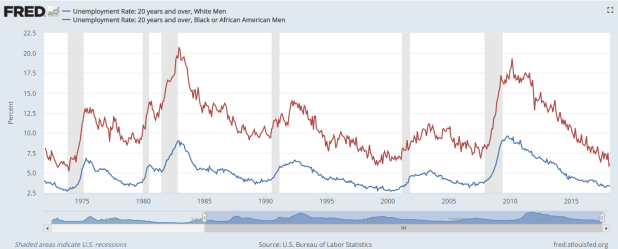

Jobs and their compensation reflect the value that a society places on an individual’s labor. The graph below is a sign of prejudice in America. The unemployment rate for blacks is always higher than the rate for whites. If this were a chart from the year 1890, the persistently higher unemployment rate could be labeled Irish or Italian. A disadvantaged class of worker is more willing to do unpleasant jobs for less money.

Under Obama, the unemployment rate for black men dropped from 18% in the spring of 2010 to 7.7% in November 2016. Since Trump’s election to the Presidency in November 2016, that rate has fallen another 20%. At 6.1% this rate is the lowest since the early 1970s. There are black grandfathers who thought they might die before seeing a younger generation enjoying an unemployment rate this low.

Still, the current rate for black men is 2.8% higher than the 3.3% rate for white men. Over the past forty years, the average difference between the two unemployment rates is close to 6%. This is the burden of being black in America. In the past half century, there have been few times when the difference in rates is this low: 1) during the Vietnam War when many black and white men were removed from the labor force; 2) 1999, near the height of the dot-com boom; and 3) several months this past year.

It’s not just skin color, religion and nationality that drives prejudice in America. Five years after the end of the Civil War in 1865, the 15th Amendment gave black males the right to vote. Women suffragettes lobbied hard to be included in the Amendment and win their right to vote. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were prominent leaders of this movement. The idea was just too crazy, they were told. Women were too guided by their emotions, and too irrational, particularly during their menses, to be trusted with the vote.

In 1920, exactly fifty years later, the ratification of the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote. The Suffragette movement had allied with the Prohibition movement to press each of their causes in a joint effort. The Volstead Act, the implementation of the 18th Amendment prohibiting the sale of intoxicating liquor, was passed a few months before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. They were a package. Had women been granted the right to vote in 1870, the Prohibition movement would have lacked a critical partner to win passage of the Amendment. Without Prohibition, the rise of organized crime might not have occurred.

Whenever there is a war, or any act of aggression with another country, Americans single out those nationalities or races for discrimination. In the 19th Century, those of Mexican descent were vilified after the Mexican-American War.

Many Germans were denied jobs and housing following the start of WW1. Historical prejudices were resurrected. German soldiers, known as Hessians, had fought with the British against American colonists in the War for Independence. Americans began to see that there was something wrong with the German character. Political cartoons pictured Germans as Huns, a mongrel and violent race of uncivilized people always lusting for battle.

Following Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. citizens of Japanese descent were forced to sell their homes and businesses at below market value, then were moved to internment camps away from the west coast.

The most recent assault on U.S. territory was the 9-11 attack by multiple suicide squads. Most hijackers were from Saudi Arabia, but we did not single out Saudi nationals in the U.S. Unlike the targets of previous war discrimination, Saudis have no unique language. Instead we singled out all Muslims, and all Arab speakers as potential threats.

Prejudice based on sex, on religion, on skin color, and on nationality have formed our country. America is built on prejudice and the passionate denial that we are a country built on prejudice. We can’t do the work of healing until we admit the reality.

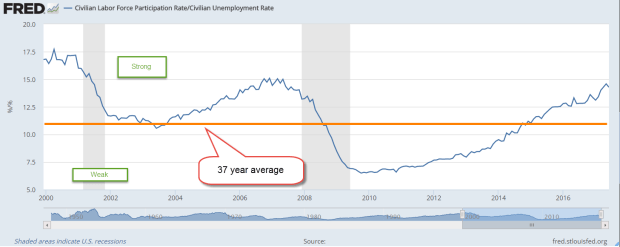

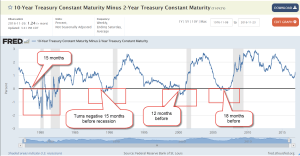

Low unemployment rates among minority groups means that the economy is especially strong. Low levels of unemployment for black, brown and white men usually precede a recession. For white men, the benchmark is 4%. For black men, it’s 7%. For Hispanic men, 5%. Below those benchmarks, the Fed has coincidentally seen what they consider to be inflationary pressures.

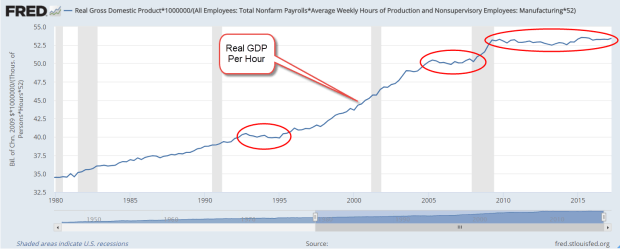

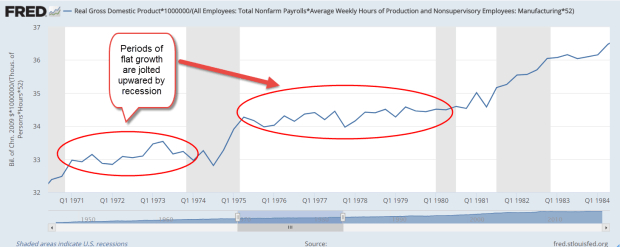

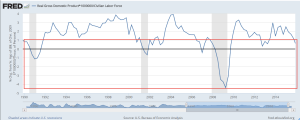

In a strong economy with low unemployment, confidence and spending increase. This puts some upward pressure on prices. Central bankers jump at the slightest hint of rising prices. Inflation and employment models like the Phillips curve are imperfect. Despite mountains of surveys, equations and data, inflation is difficult to measure, and many factors influence its rise and fall. Building a model is made more difficult because each high inflation period has had its own unique features. Among economists, fears of an awakening of the inflation beast has persisted since the recovery in 2009. Economists had begun to worry why the beast has not awoken. The models said the beast should be awake! Finally, the Fed is seeing some consistent signs that inflation is growing toward their 2% mark. It has begun to lift interest rates to curb inflationary pressures.

I’ve added the Federal Funds rate to a chart of the unemployment rate for white men to show the pattern. I’ve left off the series for black males that I showed earlier so that the chart was not too cluttered.

Economists joke that it’s the Fed’s job to remove the punch bowl just when the party is getting going. Want to know what’s ailing the stock market lately? One of them is the greater likelihood of four rate hikes by the Fed this year. At the start of the year, investors put the chances of four rate hikes at 15%. This week it stands at 45%.

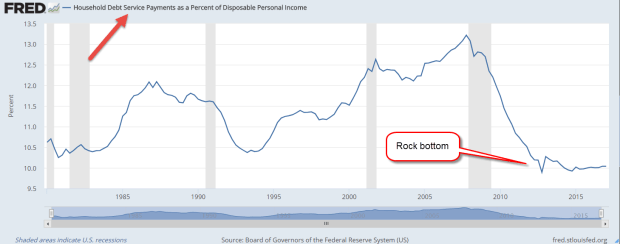

To those on the edges of our society and labor force, and to those just entering the job market, the easier job market that others have enjoyed for several years is just opening to them. If there has been a party, they have been left out. As their prospects brighten, the Fed’s raising of interest rates is a cruel joke.

As interest rates go higher, fewer people can afford to buy homes, cars and furniture. Many companies run on borrowed money to meet short term funding needs and long-term investment. As money becomes more expensive, companies tighten their belts and hiring slows. The most vulnerable are the recently hired and they are often the first to be let go. Like marine life that lives in the tidepools at the ocean’s edge, some are left high and dry when the tide of easy money ebbs.