November 16, 2014

“Yaaaaay!” Charlie erupted as he kicked the pile of leaves in the backyard. Rusted orange, dried blood crimson and mustard yellow flew up into the air. Rake in hand, George smiled at his grandson’s exuberance. “Hey, champ, let’s get these leaves in the bag.” The little arms gathered up the colored leaves and swung to the trash can which was about the same height as the four year old boy. Charlie threw the leaves up over the lip of the trash can. Very few leaves made it into the can. Charlie tilted the black plastic can toward him so that he could look in the can. “Look, Ganpa!” he exclaimed, proudly showing the inside and the few leaves that had made it into the can. “The kid’s a politician,” George remarked to his son Robbie sitting on the back deck. “Get’s very little accomplished with a lot of fanfare.”

Robbie held up his phone. “Let me get a shot of the two of you.” George picked up Charlie and held him over the trash barrel. Charlie clasped him around the neck and Robbie snapped the picture. George set the child down and the boy once again gathered up a clump of leaves and threw them up into the air. Robbie took another picture of his son. George walked over to the deck. “Let me see.” Robbie showed him the two pictures then looked at the picture of his son tossing up the leaves. He handed the phone to his dad. “Looks like a scatterplot, doesn’t it?” Robbie asked. George looked. “Wow, what have you been working on? Most people don’t see a scatterplot in a cloud of leaves.” A scatterplot is a number of data observations plotted on a graph.

“Still working on pattern recognition for drones,” Robbie said, a bit of tiredness in his voice. “A lot of tough problems to crack.” George nodded toward Charlie. “I can remember when you were this age,” George said, a fondness in his voice. Robbie went on, “Charlie – any four year old – has better visual processing that the most sophisticated algorithms we write. The brain scientists plot the paths in our brains but we still sit around the lab wondering what is it that our brains are doing when we interpret the world. Well, we just keep kicking at this mule…” His voice drifted as Charlie came over to them, leaves clenched in his little fists. He slumped on Robbie’s knees. “You need to rake more leaves, Ganpa,” he whined. George looked up and saw that Charlie had leveled the pile of leaves. “Ok, champ, let’s rake more leaves.”

Mabel opened the rear screen door. “I need a potato peeling person!” she called out. Robbie stood up. “I’ll get it,” Robbie said, “you rake.”

As he raked, George thought back to that time when Robbie was the same age Charlie was. At that time, thirty years had seemed like a lifetime because it was. He and Mabel had been in their thirties. George remembered some meetings with their accountant at the time. She had given them the talk, one that she probably gave to other young families. “You need to keep some things in mind for your kids, and for your retirement. I know it seems like a long time away now but your little boy will be in college before you know it.” The accountant was only a few years older than they were but talked like a Solon. George had supposed that the profession encouraged that kind of long term thinking. Heck, his time horizon was about five years and this woman was stretching their imagination out twenty, thirty and forty years. “The choices you make now will limit or expand your choices in the future.”

Almost thirty years later, George and Mabel had done well by following her advice over the years. George wanted to thank her but she had moved her business to Oregon or Washington and they had lost touch. They had not bought the really big house although they had sometimes wished they had more room, especially when the kids were teenagers. They had treated the two houses they had owned as a place to live, not as an investment vehicle or a store of wealth to borrow from. The mild downturn in the residential market in the early 1990s had not worried them. When the prices of homes crashed in 2007 and 2008, they lost little sleep because the mortgage was paid off. George did take a hit on his 401K though. He was close to retirement as the market tanked and both of them worried a lot through that 2008 – 2009 winter.

In the late 1980s, George had opted in for what was then a fairly new idea, a 401K plan, at work. These were termed “defined contribution” plans. The employee, not the employer, took the risk and the responsibilities for the investment allocations in the plan. The employer made its contribution to the plan and had no long term liabilities for the results that the investments did or didn’t make.

When Mabel returned to teaching in the mid 1990s, she had taken a conventional defined benefit pension plan, the only one that the school offered. In early 1999, as the Nasdaq climbed to nosebleed valuations, George had eased up on the stock allocation in his 401K. He didn’t know a whole lot about investing, only that stocks were riskier than bonds. As the market continued to climb, he sometimes regretted his decision but stuck with it as a matter of common sense. By the end of 2000, as stock prices continued to fall, he was glad he had been more conservative. In late October 2014, the Nasdaq 100 had finally climbed above the level it reached in 1999, 15 years earlier.

They enjoyed a wonderful Sunday dinner with Robbie, his wife Gail, and their grandson Charlie. Robbie asked about Emily, his sister, but no they hadn’t heard from her in almost a year. Two kids grow up in the same house. One of them is stable, has a good career, and a wonderful family. The other leads a troubled life, and is consumed by some inner demon. Emily was not a fit conversation for a dinner table so the talk moved onto other topics. Robbie, Gail and Charlie drove back to Colorado Springs that evening. There was a front moving down from Canada or Alaska so they declined the offer to stay in the guest room for the night.

There wasn’t a lot of economic news scheduled for the week so George was not expecting any strong moves in the market. Much of the earnings season had come and gone. According to FactSet almost 80% of companies had reported above consensus estimate of earnings. A more disturbing sign: three times as many companies had issued negative guidance for fourth quarter earnings as those that had indicated a more positive outlook.

The big news for the week was the Rosetta spacecraft. Launched ten years earlier, it had rendezvoused with a comet 300 million away on its journey from the far reaches of the solar system to the sun. As if that wasn’t spectacular enough, the spacecraft then launched a washing machine sized landing vehicle to sit down on the comet as it sped through space. Talk about long term planning.

On Thursday, the spot price of a barrel of crude oil dropped below $75. The Energy Information Agency (EIA) announced that the average price of a gallon of gasoline had fallen further to $2.94, the second week below $3. Several analysts pegged the price range of $65 – $70 as a “make or break” benchmark for many fracking operations. If oil were to stay down at that level for any length of time, many new drilling plans would be put on hold. Operations at existing wells might be cut back. The strong dollar meant that countries who were net exporters of oil would be paid in dollars, which could be traded for more of their own currency. For these countries, the strong dollar was helping offset the impact of lowered prices.

On Thursday, the BLS released the September report of job openings and turnover, or JOLTS. The number of employees quitting their jobs had risen to a recovery high of 2%. Workers who were not confident of finding another job did not quit their current job. Job quitters acted as a canary in a coal mine, where a relatively small part of an ecosystem or economy indicated the health of the entire system. A rate of 2% or higher indicated a healthy confidence in the employment grapevine.

On Friday, George had lunch with a few former colleagues. Four old guys sitting at a booth, drinking too much coffee. As usual, the discussion was lively. Each of them had a take on the elections just past but the conversation got a bit heated when Stan said that there were just too many people who didn’t want to work. Who was going to pay for all these people? Who was going to pay for all the government programs? He had just read a report from Pew Research that summarized the changing trends in the labor force participation rate and the sometimes contentious debates about those changes. The participation rate was the number of people working or looking for work as a percentage of the adult population, the civilian non-institutional population, as it was called. A 90 year old person could still work and was counted as part of that population of potential workers.

The core work force, those aged 25-54, showed a slightly declining participation. The first boomers had grown out of this age group at the turn of the century.

George’s opinion, one echoed by the Congressional Budget Office, was that much of the reduction in the participation rate was due to changing demographics. Since the mid-1990s, women, particularly white women, had had a historically high participation rate.

Some workers of earlier generations who had not needed a college education to earn a middle class wage found themselves less desirable in this more technological work environment. During the recession, employers shed many workers with long term health problems. As the economy improved employers were reluctant to hire these job seekers who may have had a good work ethic but possessed no above average skills or education. Some applied for disability, or retired early if they could, or simply gave up trying.

Those with college level education and higher were more likely to be working. The downtrend in the participation rate for both groups had started during the Clinton years, long before the Bush presidency, the 2008 recession or Obama’s presidency.

Full time workers as a percent of the total population were about the same level as the mid-1980s, when the economy was in a growth phase. The 1990s and 2000s had been marked by unsustainable bubbles – the dot com boom and the housing debacle.

Older workers contributed to the high participation rates of the 1990s and 2000s. A lot of people came to regard these abnormally high participation rates as normal. They weren’t, George argued.

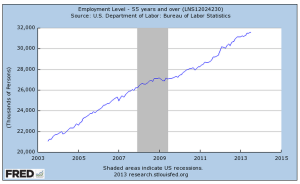

Sure, people are living longer, George argued, but the number of older workers can’t keep rising indefinitely. Since the early 1990s, older workers had risen by 20 million, from 12% of the work force to 24% of the work force. They were competing with younger workers for jobs.

27% of the entire population was older than 55. Most of that population was past working age yet older workers made up 24% of the work force.

Workers who might have retired in decades past were continuing to work, clogging up the labor pipeline.

Stan thought the economy had still not recovered and was worried about the next recession. Who’s gonna pay for all these people, he wondered again. George reminded him that average weekly hours of all private workers – most of the work force – was now at the same level as before the recession.

The Civilian Labor Force was higher now than before the recession started. The growth rate was lower but still growing.

But George agreed that there were persistent problems. A third of those unemployed had been out of work for more than a half year.

Real weekly earnings were stagnant, neither growing or declining.

There were still a lot of people who were not counted in the labor force because they were not actively looking for work. They wanted jobs but had given up. As bad as it is now, George reminded Stan, discouraged job seekers are at the same level as they were in the mid-1990s. Did you even notice back then? George asked. Stan admitted he hadn’t.

“A lot of us weren’t paying attention,” George told the group seated at the booth. “Sure, it got bad sometimes, but we figured we would get through it. This last recession was bad, bad, bad and there is a lot more information available now. We can see how bad it was five years ago and there’s plenty more information to worry over as we look to the future.”

“So, you’re optimistic?” Stan challenged. “Yeh, I am,” George replied. “Thirty years ago my accountant told me that by the time we retired, politicians would have to do one of three things: increase taxes, cut benefits, or increase the retirement age. She told Mabel and I that politicians would probably do a little of all three to spread the pain out and avoid getting thrown out of office. I was doubtful. How could she know what was going to happen so far in the future? ‘It’s just math,’ she told us. ‘The largest generation of people is going to start turning 65 in twenty-five years and the system is not designed for it. They’re gonna get sick and who’s gonna pay for it? You think the little that you pay into Medicare is going to cover that?’ I look back now at her predictions. They’ve raised the retirement age. Check. The low inflation rate is helping to reduce the growth in Social Security benefits. A half-check. Medicare costs are growing at two to three times the rate of inflation. They haven’t raised taxes yet but it’s coming.”

Stan said sardonically, “And you call yourself an optimist.” George laughed. “I guess I’m an optimist because she got Mabel and I planning for all of this a long time ago. When they raised the retirement age, we weren’t surprised. When they cut Social Security benefits in the future, we won’t be surprised. When they raise taxes, we won’t be surprised.”

“Is this lady still your accountant? She sounds pretty smart.” Stan asked. “No,” George replied. “I think she and her husband moved to Oregon or Washington. They wrote business and investment software but they gave up trying to defend their software from copying. This was in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Even their own clients were copying their software and giving it to their friends. ‘Smaller companies like ours just don’t have the time or resources to protect against theft,’ she told us. ‘Eventually we’ll go to work as consultants for the larger companies.’ And several years later, that’s what they did.”

The waitress brought the check. Normally they would split it four ways but Stan picked it up and handed it to George. “Shouldn’t the optimist pay?” George laughed. “This one time,” he said, “but on one condition. You all have to agree with me. Isn’t that how they do it in politics?” They all laughed, grunting as they straightened up after sitting so long.