In a Aug. 25th Wall St. Journal op-ed editorial board member Stephen Moore compared Obamanomics and Reaganomics. Both Presidents inherited crippled economies but after 2.5 years in each President’s term there is a sharp contrast in GDP growth. In 1983, growth was about 5%. In 2011, it is about 1%. Mr. Moore attributes the healthy growth of the Reagan administration to Reagan’s focus on the supply side of the economy. Obama’s policies, on the other hand, focus on the demand side of the economy. I argue that Mr. Moore has neglected a major component of the economy that accounts for the differences in growth – household debt. Consumer purchases account for roughly 70% of GDP. When consumers go on a decades long buying binge, GDP growth is strong. When consumers get choked with debt, as they had toward the end of this past decade, they pay down that accumulated debt and GDP shrinks accordingly or grows much more slowly.

In the late 70s, consumer borrowing began a rapid rise that would soon skyrocket in the following decades. The first half of the Boomer generation were in their early 30s and late 20s. Rampant inflation created a dangerous attitude of “buy now, pay later” as a way to save money as prices roses more than 10% per year. Not in wide use in previous decades, credit cards began growing in popularity among this new generation. This largest generation began settling down to start families, buying houses and cars with easy credit.

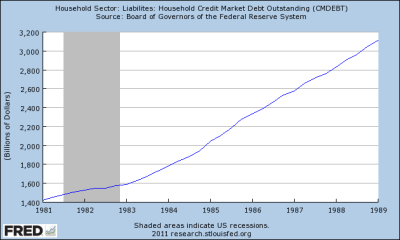

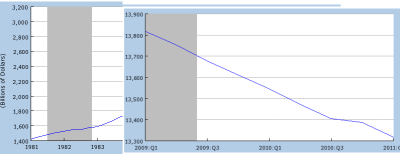

From 1973 to 1981, household debt grew 2.5 times, from $578 billion to $1422 billion. As the chart below shows, household debt more than doubled again to $3110 billion, or $3.1 trillion, during the Reagan administration. (Click to enlarge in separate tab)

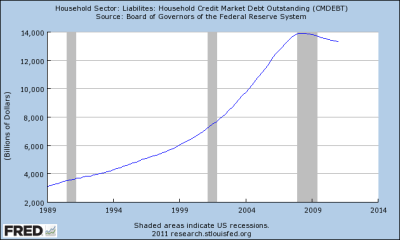

During the next eight years from 1989 to 1997, the growth rate of household debt slowed to 168% but topped $5 trillion. This slowdown was due mostly to the recession of the early nineties. As we pulled out of the recession in 1993, we returned to bingeing on debt. In the eight years from 1997 to 2005, that debt doubled again to almost $11 trillion.

In Jan. 2008, household debt outstanding stood just shy of $14 trillion dollars, or about the total nation’s GDP.

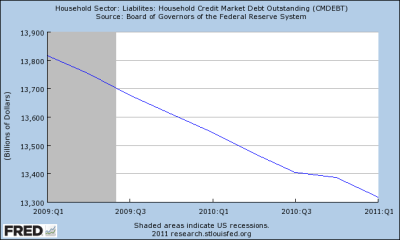

After growing for almost 6 decades, the debt burden on families had reached an unsustainable peak and it began to fall. In January 2011, the total is still over $13 trillion but has fallen 4.4% since January 2008.

The composite chart below gives a clearer picture of an important contrast between the early eighties and the past 3 years.

Supply side economic policies which offer greater support to suppliers, i.e. less regulation and lower taxes, won’t have much effect when buyers are overextended and the demand is not there. The greatest asset base of most households is their home, a base that has severely eroded. House foreclosures continue to climb and there is a large pool of delinquent mortgages that are waiting to be foreclosed on. The large loss of jobs has slashed the credit card borrowing capacity of many households. New car sales contributed to the growth in household debt but have plummeted in the past few years. They have improved over the past few months but are still 70% of 2007 levels. Many consumers are wary of taking on more debt. Without that consumer demand, companies are understandably reluctant to invest in new buildings, to build inventory, to expand their business capacity. This is why American companies are sitting on almost $2 trillion in cash.

Why did so many of us run up so much debt? The income of the middle class, in inflation adjusted dollars, stopped growing after 2000 (same Census Bureau table as above). To make up for the lack of growth, households borrowed against their houses and ran up credit card debt and car loans and leases. The real growth in middle class incomes over the past 30 years is only 15%, or 1/2% per year average.

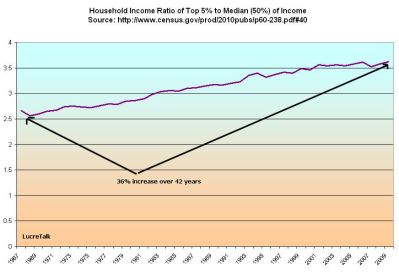

During the past thirty years, the distibution of income has favored the top 5% of households, those making more than $180K (in 2009 dollars). Below is a chart of the growing ratio of the top 5% of incomes to the median, or middle, income.

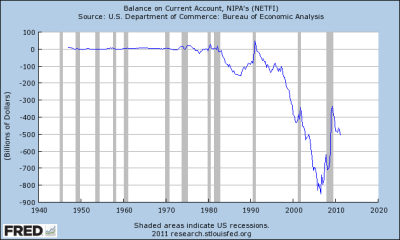

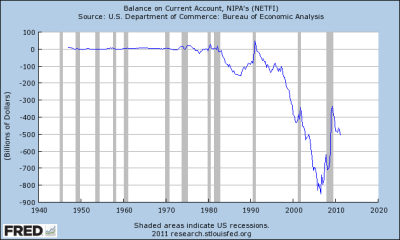

That ratio has grown 36% over the past 42 years. The fortunes of the top income earners are pulling away from the rest of the country and will continue to do so as we continue to import far more than we export. Exports produce American jobs. Imports reduce American jobs. Below is a chart of the Balance of Accounts for the past 60 years showing the balance of exports minus imports. In the 1990s, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) moved many jobs to Mexico but the real exodus of jobs from the U.S. occurred after China was admitted into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Since then, 4 million manufacturing jobs have been lost in the U.S.

Due to increased productivity, manufacturing has been declining for the past forty years (U.N. chart here) in both the U.S. and the world. Both industrialized and newly industrializing nations are relying more on the service sector of their economies for the bulk of their GDP. In this country, manufacturing jobs produced greater income relative to educational experience. A person with a high school education could earn an income that would put them at the median income level or above. Today, the construction industry is the only large sector that can consistently provide that kind of income with only a high school education. The decline in housing has crippled that industry and slashed the incomes and job prospects of many.

The growth of the early eighties was fueled by the advent into the workplace and marketplace of the largest generation ever, the newly maturing Boomers who built families and businesses and borrowed and borrowed but who are now near retirement. Reagan stands near the beginning of that economic expansion fueled by debt. Obama stands at the collapse of that runaway debt explosion. Reagan’s policies did not jump start the growth process nor do Obama’s policies hinder it. The sociological and economic forces of a generation surpasses either’s politics or policies.