September 25, 2016

Almost daily I read about the coming implosion in the stock market. There are only two price predictions: up and down. One of them will be right. So far, no catastrophe, so why worry? Should an innocent investor just Ease On Down the Road? (Video from the 1978 movie).

Unfortunately, the stock market road looks like Rt. 120 south of Mono Lake in California. The road is like a ribbon, marked by highs that are many years apart, more years than the majority of us will live in retirement. In the graph from below from multpl.com I have marked up the decades-long periods before the inflation adjusted SP500 surpassed a previous high. It is truly humbling.

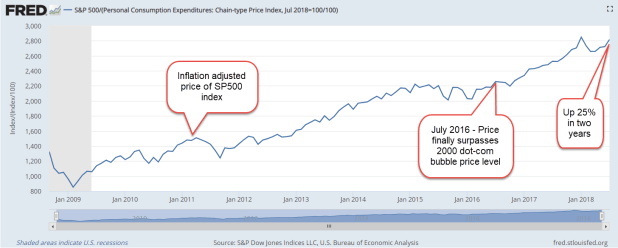

It took 23 years for the market to finally surpass the high set in 1906. Happy days! Well, not quite. Several months later came the stock market crash of 1929. In 1932, the market fell near the 1920 lows. In 1956, 27 years after the ’29 crash, the market finally notched a new high. In more recent decades, the market spent 23 years in a trough from 1969 to 1992. Lastly, we have this most recent period from the high set in 2000 to a new high set in 2015.

IF – yes, the big IF – a person could call the high in a market, that would sure be nice, as Andy Griffith might say. (Youngsters can Google this.) Of course, Andy would be suspicious of any city slicker who claimed to have such a crystal ball. Knowing the high mark in advance is magic. Knowing a previous high is not magic.

Looking at the chart we can see that the price in each period falls below the high of the period before it. In the period marked “1” in the graph, the price fell below the high set in 1892. In period marked “2”, the price fell below the high set in 1906. In the period marked “3”, the price fell below the high set in 1929. In this last period marked “4” the price – well, it never fell below the high set in 1969. The run up in the 1990s was so extreme that the market still has not truly corrected, according to some. Even the low set in 2008 didn’t come close to falling below the highs of that 1969-1992 period. An investor who used a price rule that had been good for more than a hundred years found that the rule did not apply this time.

In 2008-2009, why didn’t prices fall below the high of the 1969-1992 period? They would have had to fall below 500 and in March 2009, there were a number of market predictors calling for just that. On March 9th, the SP500 index closed at 676, after touching a low of 666 that day. The biblical significance was not lost on some. Announcements from major banks that they had actually been profitable in January and February caused a sharp rebound in investor confidence. The newly installed Obama administration had promised some economic stimulus and the Federal Reserve added their own reassurances of monetary stimulus.

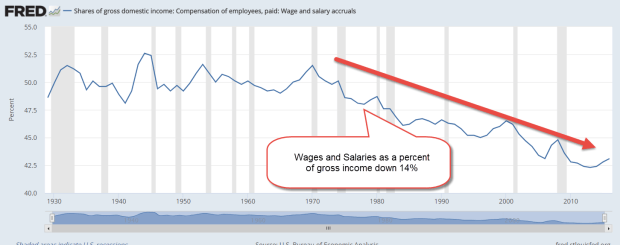

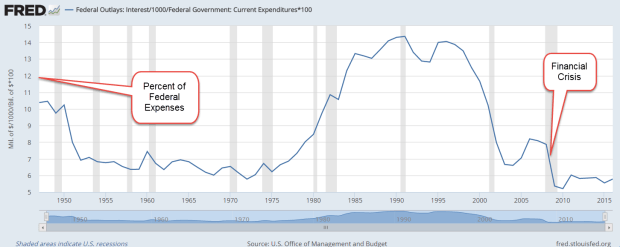

Did these fiscal and monetary relief measures prevent the market from fully purging itself? Maybe. Are stock prices wildly inflated because the Federal Reserve has kept interest rates so low for so long. Could be. How low are interest rates? In 2013 the CBO predicted interest rates of 3-4% by this time. They are still less than 1/2%.

How much are stock prices inflated? Robert Shiller, the author of “Irrational Exuberance,” devised a price earnings ratio that removes most of the natural swings in earnings and the business cycle. Called the Cyclically Adjusted Price Earnings ratio, or CAPE, it divides the current price of the SP500 index by a ten year period of inflation adjusted earnings. The current CAPE ratio is just below the high ratio set in 2007 by a market riding a housing boom. The only times when the CAPE ratio has been higher are the periods during the housing bubble (2008), the dot-com boom (2000), and the go-go 1920s when many adults could buy stocks on credit. Each of these booms was marked by a price bust that lasted at least a decade.

Price rules require some kind of foresight, and crystal balls are a bit cloudy. There is a strong argument to be made for allocation, a balance of investments that generally are non-correlated, i.e. one investment goes up in price when another goes down. An investor does not have to frequently monitor prices as with price rules. A once or twice a year reallocation is usually sufficient.

In an allocation strategy, equities and bonds are the most common investments because they generally counterbalance each other. A portfolio with 60% stocks and 40% bonds, or 60/40, is a common allocation. (Some people write the bond allocation first, as in 40/60.) Shiller has recommended that an investor shift their allocation balance toward bonds when the CAPE ratio gets this high. For example, an investor would move toward a 60% bond, 40% stock allocation.

To see the effects of a balanced allocation, let’s look at a particularly ugly period in the market, the period from 2000 through 2011. The stock market went through two downturns. From 2000-2003, the SP500 lost 43% (using monthly prices). The decline from October 2007 to March 2009 was a nasty 53%. In 2011 alone, a budget battle between the Obama White House and a Republican Congress prompted a sharp 20% fall in prices. During those 12 years, the SP500 index lost about 10%, excluding dividends.

During that period, a broad bond index mutual fund (VBMFX) more than doubled. Equities down, bonds up. A rather routine portfolio composed of 60% stocks and 40% bonds had a total return of 3.75% per year. Considering the stock market losses during that period, that return sounds pretty good. Inflation averaged 2.6% so that balanced portfolio had a real gain of about 1.2%. Better than negative, we reason. On the other hand, a portfolio weighted at 40% stocks, 60% bonds had a total annual return of 4.75%, making the case for Shiller’s strategy of shifting allocations.

There is also the nervousness of a portfolio, i.e. how much an investor gets nervous depending on one’s age and the various components of a portfolio. During the 2000-2003 downturn in which the SP500 lost 43%, an investor with a 60/40 allocation had just 14% less than what they started with in the beginning of 2000. Not bad. 2008 was not pleasant but they still had 11% more than what they started with. That is a convincing case for a balanced portfolio, then, even in particularly tumultuous times.

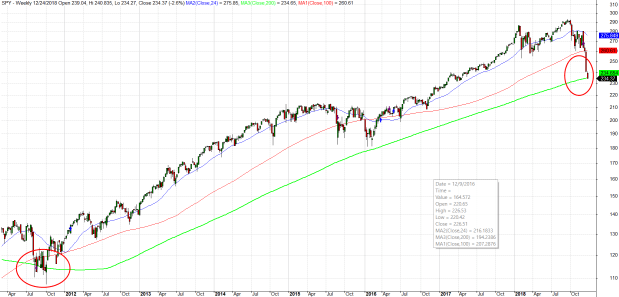

Can an investor possibly do any better by reacting to certain price triggers? We already discussed one price rule that was fairly reliable for a hundred years till it wasn’t. The problem with rules are the exceptions and it only takes one exception to bruise an average 20 year retirement cycle. Another price rule is a medium term one, the 50 day and 200 day averages. These are called the Golden Cross and Death Cross. Rules involve compromises and this rule is no exception. In some cases, an investor may sell just when the selling pressure has mostly been exhausted. Such a case was July 2010 when the 50 day average of the SP500 crossed below the 200 average, a Death Cross, and triggered a sell signal. The market reversed over the following months and when the 50 day average crossed back above the 200 day average, a Golden Cross, an investor bought back in at a price 10% higher than they had sold!

The same scenario happened again in August 2011 – January 2012, buying back into the market in January 2012 at a price 10% higher than the price they sold at in August 2011. These short term price swings are called whipsaws and they are the bane of strict price rules. In the past year there were two such whipsaws, one of them causing a 5% loss. Clearly, this traditional trading rule needs a toss into the garbage can! What works for a few decades may fail in a later decade.

For those investors who want a more active approach to managing a portion of their portfolio, what is needed is a flexible price rule that has been fairly reliable over six decades. As a bull market tires, the monthly price of a broad market index like the SP500 begins to ride just above the two year average. The monthly close will dip below that benchmark average for a month as the bull nears exhaustion. If it continues to decline, that is a good indication that the market has run its course. The price rule is an attention trigger that may not necessarily prompt action.

Let’s look at a few examples. President Kennedy’s advisors were certainly aware of this pattern when the market fell below the two year mark in 1962. They began pushing for tax cuts, particularly for those at the highest levels. Rumors of a tax cut proposal helped lift the market back above the benchmark by the end of 1962 In early 1963, JFK made a formal proposal to lower personal rates by a third and corporate rates by 10% (At that time, corporations paid a 52% rate). An investor who sold after a two month decline suffered the same whipsaw effect, buying back into the market at about 10% higher than they sold. However, at that selling point in 1962, rumors of tax cuts were helping the market rebound and might have caused an investor to wait another week before selling. The market had in fact reached its low.

In mid-1966, the SP500 fell below its 24 month benchmark for seven months. Escalating defense spending for the Vietnam War helped arrest that decline.

The bull market finally tired in the summer of 1969 and dropped below the 24 month benchmark in July. The index treaded water just below the benchmark for a few months before starting a serious decline of 25%. More than a year passed before the monthly price closed above the benchmark in late 1970.

The 1973 Israeli-Arab war and the consequent oil embargo threw the SP500 into a tailspin. The price dipped below the average a few times starting in May 1973 before crossing firmly below in November 1973. After falling almost 40%, the price finally crossed back above the benchmark in late 1974. Remember that this was a particularly difficult fourteen year period marked by war, high unemployment and inflation, and a whopping four recessions. The SP500 crossed below its ten year – not month, but year – average in 1970, again in 1974-75, and lastly in 1978. Such crossings happen infrequently in a century and are great buying opportunities when they do happen. To have it happen three periods in one decade is historic.

I’ll skip some minor events in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In most episodes an investor can take advantage of these opportunities to step aside as the market swoons, then buy back in at a price that is 5-10% lower when the market recovers.

The most recent episodes were in November 2000 when the SP500 fell below its benchmark at about 1300. When it crossed back over the benchmark in August 2003, the index was at 1000, a nice bargain. This was another crossing below the ten year average. The last one was in 2008 when the monthly price fell below the benchmark in January. Although it skirted just under the average it didn’t cross back above the 24 month average. In June it began a decline that steepened in September as the financial crisis exploded. Again the index fell below its ten year average. By the time the price closed back above the benchmark in November 2009, an investor could buy in at a 20% discount from the June 2008 price.

In September 2015 and again in February of this year, the index dropped briefly below its 24 month average. They were short drops but it doesn’t take much of a price correction because the index is riding parallel with the benchmark, above it by only 100 points, or less than 5%. Corporate profits have declined for five quarters. The bull is panting but still standing.

As we have seen in past exhaustions, there is a lot of political pressure to do something. What could refuel the bull market? Monetary policy seems exhausted. The Federal Reserve has indicated that they will use negative interest rates if they have to but they are very reluctant to do so. Just this past week, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) indicated that their policy of negative interest rates is not helping their economic growth. The BOJ had started down a negative interest rate path and has now warned other central banks not to follow.

What about fiscal policy? The upcoming election could usher in some fiscal policy changes but that seems unlikely. Donald Trump has joined with Democrats advocating for more infrastructure spending but that is unlikely to pass muster with a conservative House holding the purse strings and a federal public debt approaching $20 trillion. Only sixteen years ago, it was less than $6 trillion. Democrats keep reminding everyone that the Federal Government can borrow money at very cheap rates. However, the level of debt matters and Republicans will likely control the money in this next Congress.

Managing an entire portfolio with a price rule is a bit aggressive but might be appropriate for some investors who want to take a more active approach with a portion of their portfolio. This price rule – or let’s call it guidance – is more a pain avoidance tool than a timing tool.