August 3, 2014

Employment

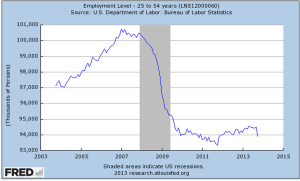

The employment report for July was moderately strong but below expectations. Year-over-year growth in employment edged up to 1.9%, a level it first touched in March of 2012.

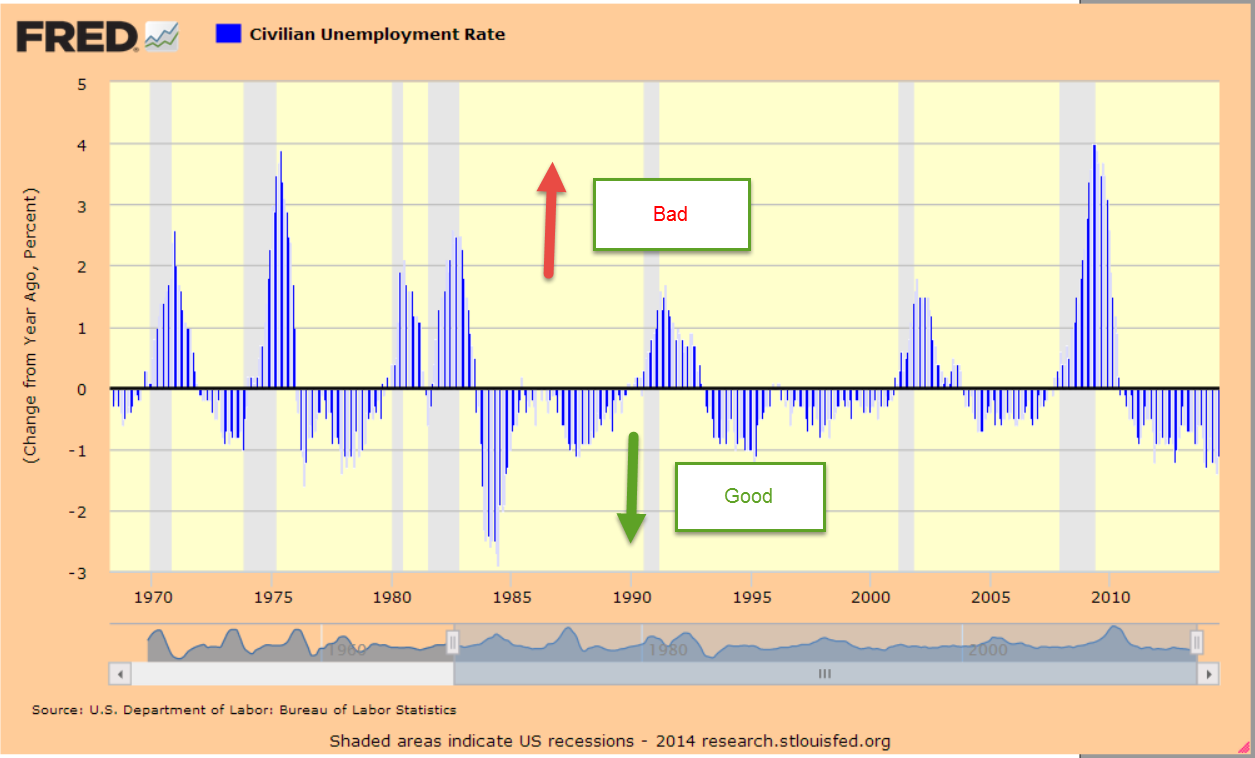

The unemployment rate ticked up a notch after ticking down two notches last month. Notches can distract a long term investor from the underlying trend, which is positive. Comparing the year-over-year percent change in the unemployment rate gives a good overall view of the economy and the mid term prospects for the stock market.

There was some slight improvement in the Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate this month. The decline in the participation rate has been worrisome. When we view the unemployment rate as a percentage of the Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate, we do see a continuing decline in this ratio, which is positive. From early 2002 to early 2003, the market continued its decline even after the end of a fairly mild recession. Employment gains were meager, prompting concerns of a double dip recession. Should this ratio start to increase over several months, investors would be wise to start digging their foxholes.

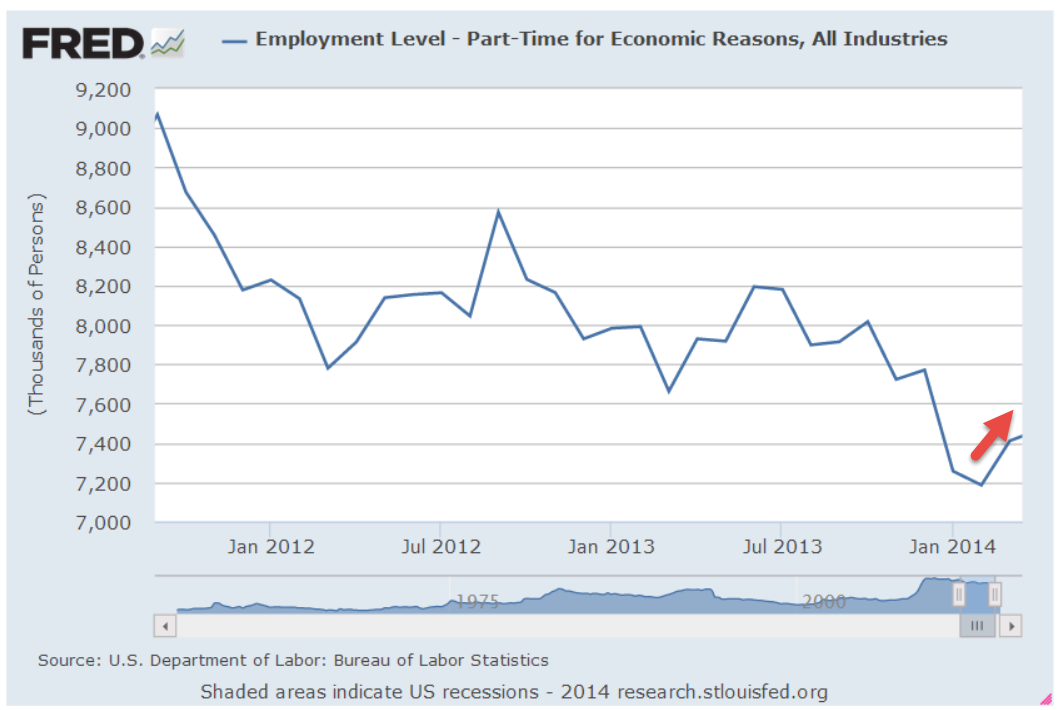

Employment numbers can hide weaknesses in the labor market. After falling to a low of 7.2 million this February, people working part time because they can’t find full time work has climbed up 300,000 to 7.5 million. The good news is that the ranks of involuntary part-timers has dropped by 700,000, or 8.5%, from July 2013 to this July.

Employment in service occupations makes up almost 20% of the work force and usually peaks in July of each year after a January trough. The numbers come from the monthly survey of business payrolls so it affects the job gains number to some degree, depending on the seasonal adjustments. I expected this month’s report to show the normal pattern, rising up at least 50,000 from June’s total of 26.54 million. I was surprised to see that employment in this composite had dropped by 170,000 in July.

Unlike the majority of years, this year’s trough occurred in February, one month later than usual. This may be weather related. 1998, 2003, 2005, 2011 were also years in which the trough occurred one month late. Over the past twenty years, the peak has always come in July – until this year.

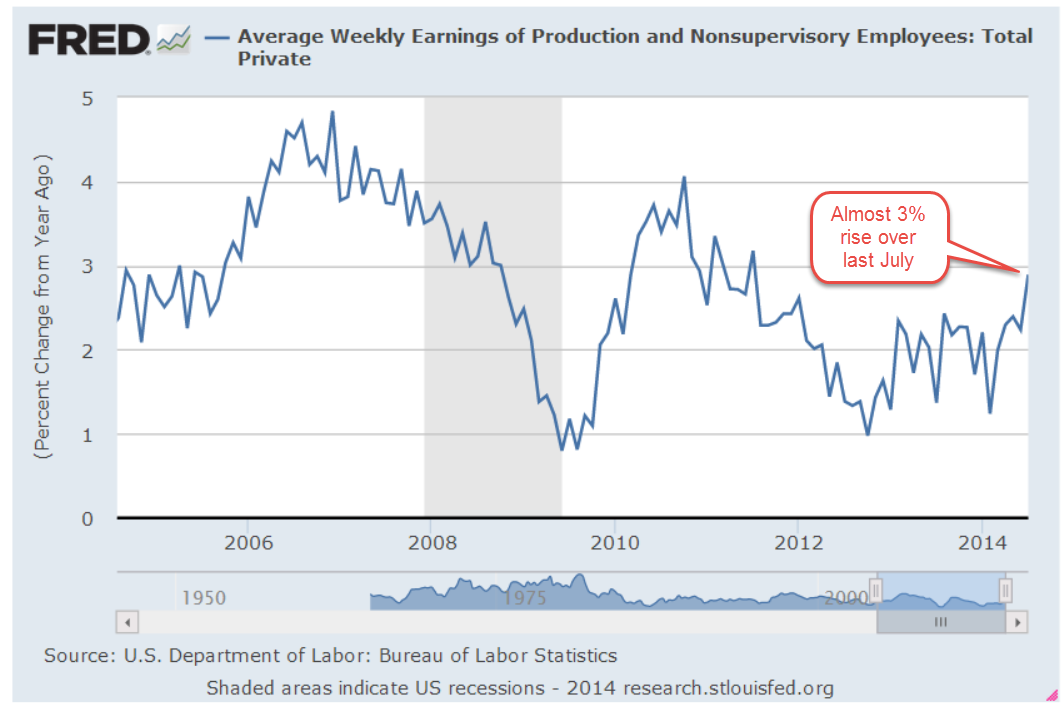

Hourly wages have grown 2% in the past twelve months, meaning that there is no gain after inflation. That’s the bad news. The good news is that weekly earnings for production and non-salaried employees this July bested July 2013 earnings by 2.9%.

************************

Auto Sales

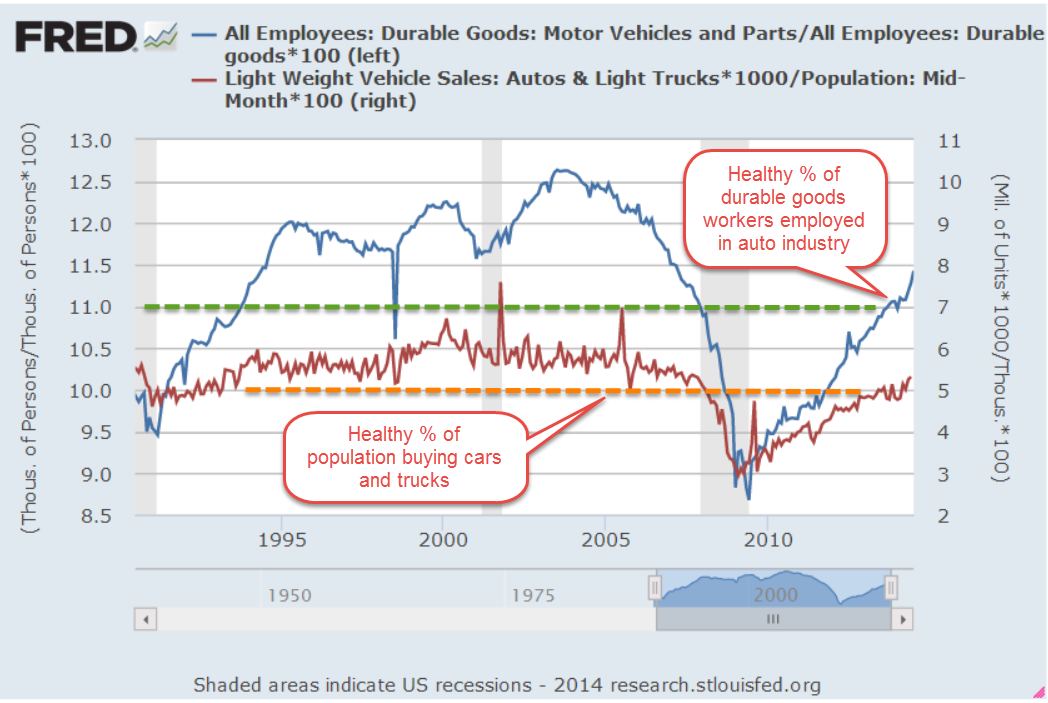

July’s vehicle sales slipped 2.4% from June’s annualized pace of 16.9 million vehicles. Robust vehicle sales are due in part to an increase in sub-prime loans, which have grown to 30% of new car loans. A few weeks ago, the N.Y. Times published an article describing some auto loan application shenanigans.

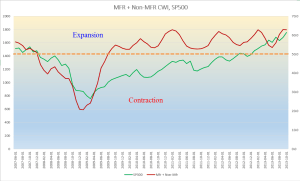

The casual reader may not understand the significance of numbers in the millions so I created a chart showing numbers in the hundreds. The manufacturing of cars is part of a broader category called durable goods. If a 100 workers are employed making durable goods, we would like to see at least 11 of them making cars or parts for cars. In a healthy economy, 5 people out of 100 buy a car or truck. The chart below shows the relationship between the number of people buying cars and the percent of durable goods workers making cars. The chart is a bit “busy” but I hope the reader can see that, despite talk of an auto bubble that could crash the market, the percent of the population buying cars is just barely above the minimum healthy level.

There may be a bubble in auto financing but not auto sales. Secondly, a vehicle can be repossessed and resold much more easily than evicting a delinquent homeowner.

***********************

GDP

The first estimate of 2nd quarter GDP was 4% annualized growth, above the 3% consensus expectations. Under the hood, we see that 1.7% of that 4% is a build up of inventories. This mirrors the 1.7% negative change in inventories in the first quarter, as I noted in last month’s blog. It is not a coincidence and should remind us that these are human beings making a first estimate of the entire economic activity of a country.

Let’s put this early estimate in perspective. The year-over-year percent growth is 2.4%, above the 1.6% average y-o-y growth of the past ten years. Let’s get out our magic wand and take away the recessionary four quarters in 2008 and two quarters in 2009. Let’s add some good numbers in late 2003 and early 2004 as the economy recovered from the dot com boom period. Presto chango! Well, not so presto. We see that the average over these 37 quarters, just a bit more than 9 years, is still only 2.3%.

From 1970 – 2007, the average is 3.1%, or almost double the 1.6% average of the past ten years. The Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world have employed the tactics at their disposal to avert deflation and to spur lending. While low interest rates and bond purchases have accomplished some of those goals, they have created some distortions in the markets, putting upward pressure on both equity and bond valuations. Higher stock prices pressure companies to produce the profits – on paper, at least – that will justify the increased valuation. In the past this has induced some companies to pursue a course of – an appropriate term might be “aggressive” accounting – to meet investor demands.

So this first estimate of GDP for the 2nd quarter is slightly above the magic wand average of the past decade and way above the real ten year average. Not bad. I’m guessing that the second estimate of 2nd quarter GDP, released near the end of August, will be revised downward but even if it is, economic growth is better than average.

***********************

Construction Spending and Employment

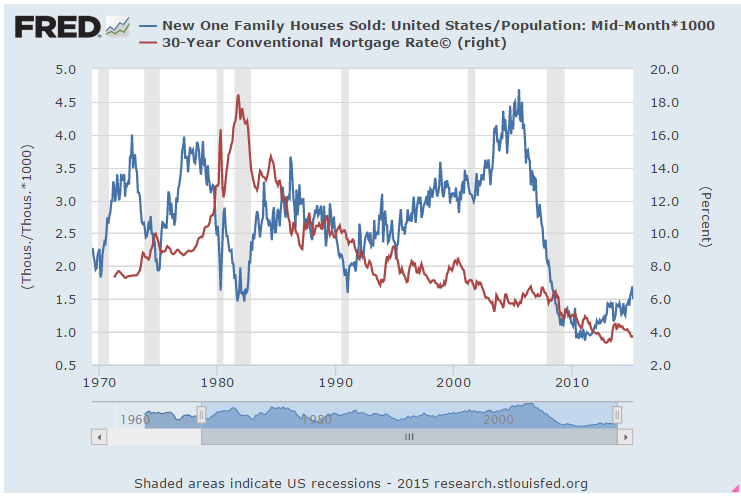

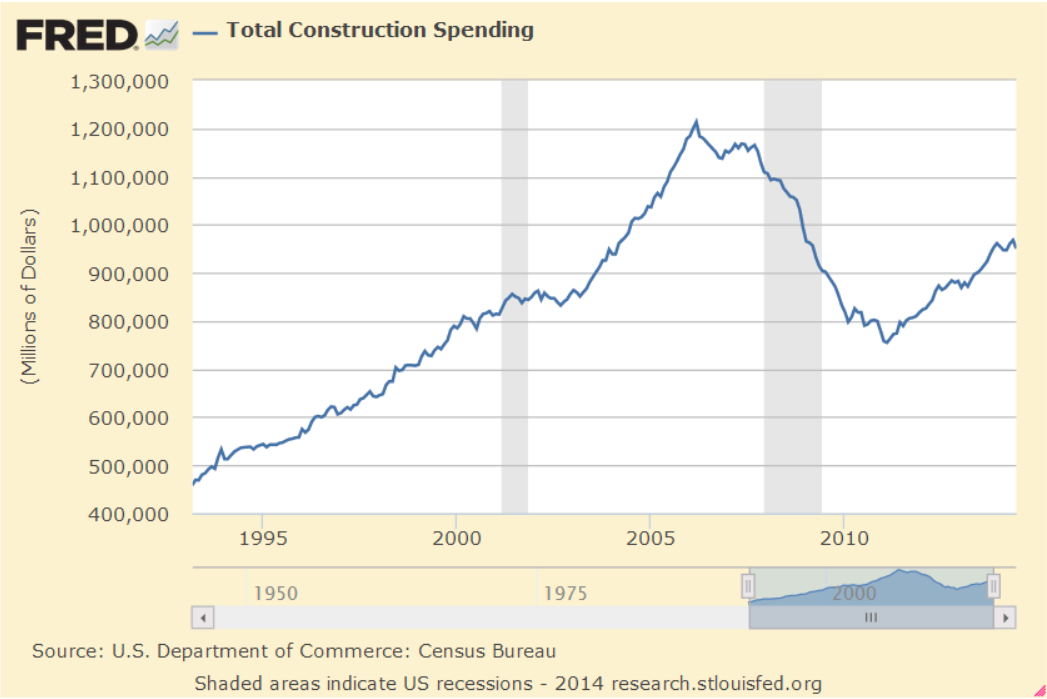

Construction added 20,000 jobs in July, and are up 3.6% above July of 2013. Total Construction spending includes residential and commercial buildings, public infrastructure and transportation. Spending in June declined almost 2% from a strong May but is up more than 5% from last year. A casual glance at the spending numbers might lead one to observe that, after the housing boom and bust, the construction sector is on the mend.

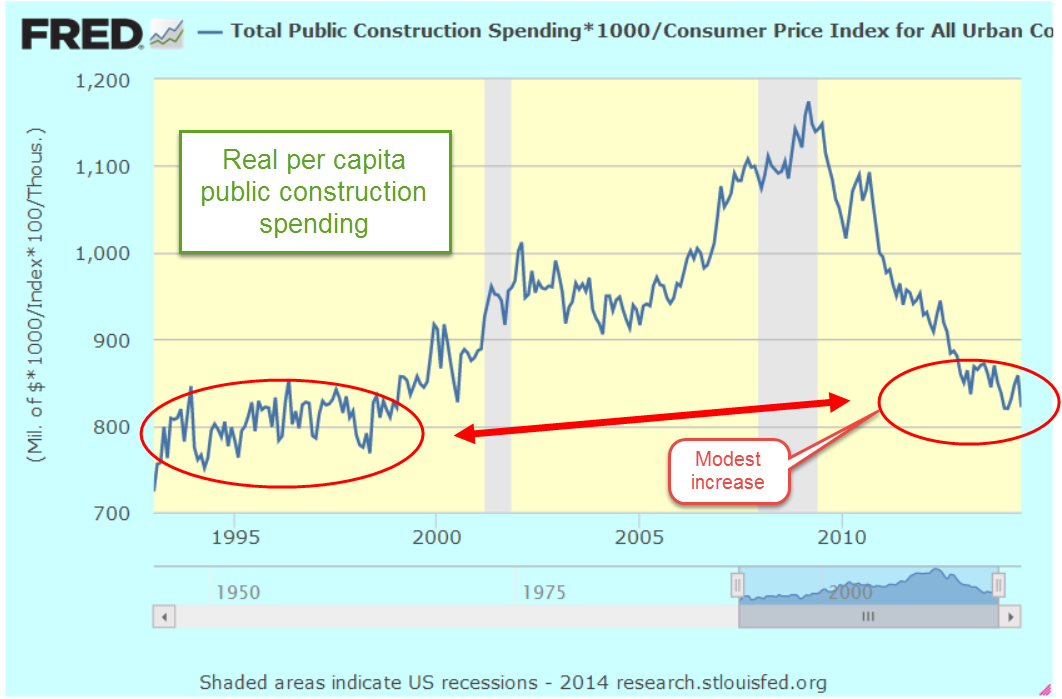

The underlying reality is that further improvements in construction spending may be modest. The chart below shows real, or inflation adjusted, per capita spending. What was good enough in 1994 may be equally good in 2014 and beyond.

Residential construction has leveled off just slightly below what is probably a sustainable zone of $1200 to $1600 per person spending. At the height of the housing boom, per person spending was almost twice that of the midline $1400 per person. Corrections to such severe imbalances are painful.

While many of us think that the boom was all in the residential sector, per person construction of public infrastructure had its own boom, growing almost 50% from the levels of the mid-90s. Some economists and politicians continue to advocate more public construction as a Keynesian stimulus but we can see below that real per-capita public spending today is slightly more than the levels of the mid-1990s.

Spending on public infrastructure including highways helped buffer the downturn in residential construction. As a percent of total construction spending, it is still contributing more than its share to the total. If residential construction were just a bit stronger, this percentage would drop to a more normal range closer to 25%.

Workers in their thirties now came of age at a time when “normal” in the construction sector was far above normal. Policy makers grew to believe that this elevated level of spending was evidence of a strong economy. They believed they were masters of the economy, ushering in a new normal of prudent fiscal policy that worked in tandem with assertive government policy to promote housing investment that would lift up those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

Today we don’t hear as much from those masters of economic and social engineering. Their names include former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, former President George Bush, former Congressman Barney Frank, and current Congresswoman Maxine Waters. Each of them might point to the mis-managers who helped pump up the housing balloon. They include former Fannie Mae head Franklin Raines, and Kathleen Corbett, the former president of the ratings agency Standard and Poors which slapped a pristine AAA rating on the good and the bad. “Kathleen is an advocate of best practices, fiscal responsibility and effective management” reads Ms. Corbett’s page at the New Canaan Town Council.

Then there are the crooks who knew what their companies were doing was dangerous, if not wrong. Topping that list is Angelo Mozilo, the head of Countrywide Financial, the largest originator of sub-prime loans. “Crooks” is the term Mr. Mozilo once used to describe companies who wrote sub-prime mortgages. If the suit fits, wear it.

A crook needs a fence to move the goods and there were two prominent ones in this side of the game: Dick Fuld, the former head of Lehman Bros, and Stan O’Neal, the former head of Merrill Lynch. Both companies made a lot of sausage out of sub-prime mortgages.

Thank God that’s all behind us. Hmmm, we said that after the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s. Well, thank God that’s all behind us till the mid-2020s, when we will repeat our mistakes. A retiree should consider that during their retirement an episode of foolishness and downright dishonesty will likely have a serious impact on the value of their portfolio.

*************************

Takeaways

Continued strength in employment, with some weaknesses. Estimate of 2nd quarter GDP growth probably a tad high. Construction spending still just a bit below the historical per-capita channel of spending.