August 18, 2019

by Steve Stofka

Two quick asides before I get into this week’s topic. A cricket perched on the top of a 7′ fence. It drew up to the edge of the top rail, learned forward, raised its rear legs as though to jump, then settled back. It did this twice more before jumping 8′ out then down into a soft landing on some ground cover. How far can crickets see, how often do they injure a leg if they land incorrectly and do they get afraid?

The bulk of the personal savings in this country is held by the top 20% of incomes, and it is this income group that received the lion’s share of the 2017 tax cuts. It’s OK to bash the rich but that top 20% probably includes our doctor and dentist. Before you start drilling or cutting me, I want to make it perfectly clear that I was not criticizing you, Doc.

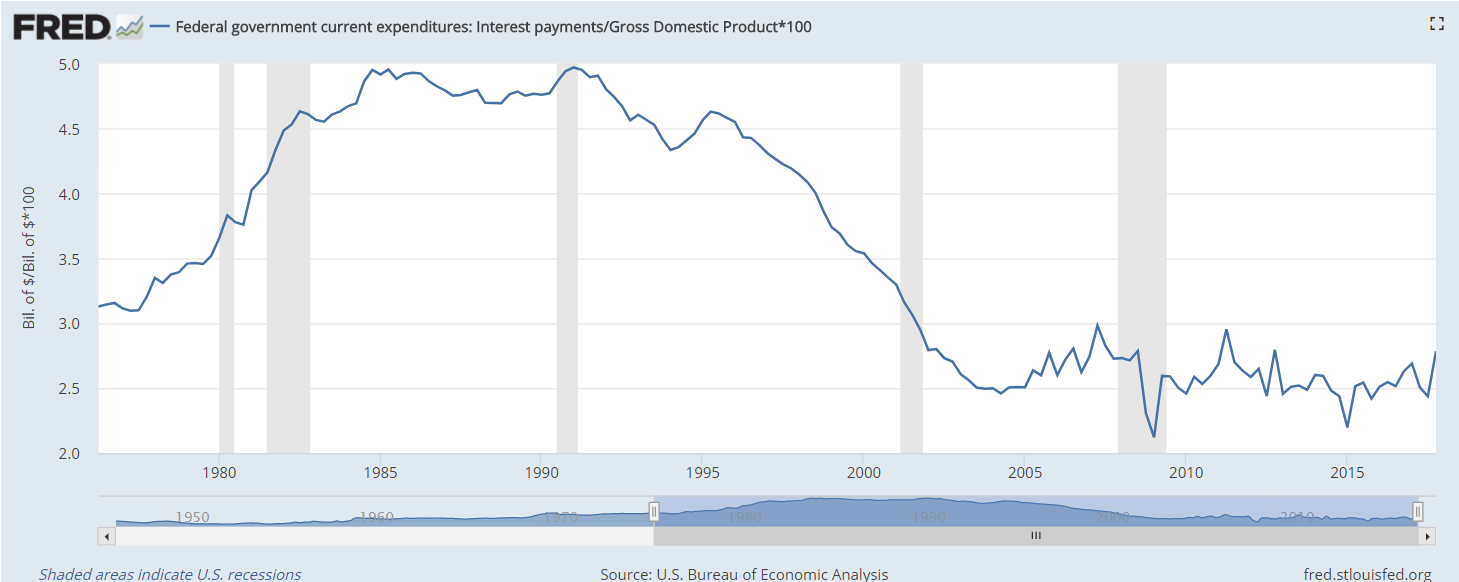

In 2016, the top quintile – the top 20% – earned 2/3rds of the interest and dividend income (Note #1). Due to falling interest rates over the past three decades, real interest and dividend income has not changed. Real capital has doubled and yes, much of it went to those at the top, but the income from that capital has not changed. That is a huge cost – a hidden tax that gets little press. The real value of the public debt of the Federal Government has quadrupled since 1990, but it pays only 20% more in real interest than it did in 1990 (Note #2). Here’s a graph of personal interest and dividend income adjusted to constant 2012 dollars. Thirty years of flat.

Ok, now on to a story. Economists build mathematical models of an economy. I wanted to construct a story that builds an economy that gradually grows in complexity and maybe it would help clarify the relationships of money, institutions and people.

Let’s imagine a group of people who move into an isolated mining town abandoned several years earlier. The houses and infrastructure need some repairs but are serviceable and the community will be self-sufficient for now. The homeowners form an association to coordinate common needs.

The association needs to hire lawn, maintenance and bookkeeping services, and security guards to police the area and keep the owners safe. How does the association pay for the services? They assess each homeowner a monthly fee based on the size of the home. How do the homeowners pay the monthly fee? Each homeowner does some of the services needed. Some clean out the gutters, others fix the plumbing, some keep the books and some patrol the area at night. They work off the monthly fee.

How do they keep track of how much each homeowner has worked? The association keeps a ledger that records each owner’s fee and the amount worked off. The residents sometimes trade among themselves, but it is rare because barter requires a coincidence of wants, as economists call it. Mary, an owner, needs some wood for a project and Jack has some extra wood. They could trade but Mary doesn’t have anything that Jack wants. He tells Mary to go down to the association office and take some of her time worked off her ledger and credit it to Jack’s monthly fee. Mary does this and they are both happy (Note #3).

As other owners learn of this idea and start trading work credits, the association realizes it needs a new system. It prints little pieces of paper as a substitute for work credits and hands them out to owners who perform services for the association. These pieces of paper are called Money (Note #4).

The money represents the association’s accounts receivable, the fees owed and accruing to the association, and the pay that the association owes the owners for the work they have done. Then the association notices that there are some owners who are not doing as well as others. It assesses an extra fee each month from those with larger homes and gives that money to needy homeowners. These are called transfers because the owners who receive the money do not trade any real goods or services to the association. In this case the association acts as a broker between two people. Let’s call these passive transfers. We can lump these transfers together with exchanges of goods and services.

Then some people from outside the area start stealing stuff from the homeowners. The association needs to hire more security guards, but homeowners don’t want to pay a special one-time assessment to pay for the extra guards.

Instead of printing more Money, the association prints pieces of paper called Debt. Homeowners who have saved some of their money can trade it in for Debt and the association will pay them interest. Homeowners like that idea because Money earns no interest and Debt does. The association uses the Money to pay for the extra security guards.

But there are not enough people who want to trade in their Money for Debt, so the association prints more Money to pay the extra security guards.

Let’s pause our story here to reflect on what the words inflation and deflation mean. Inflation is an increase in overall prices in an economy; deflation is a decrease (Note #5). Inflation occurs when the supply of money fuels a demand for goods and services that is greater than the supply of goods and services. Ok, back to our story.

So far so good. All the Money that the association has printed equals a trade or a passive transfer. Let’s say that the association needs more security guards and no one else wants to work as a security guard because they can make more Money doing jobs for other homeowners. The association makes a rule called a Draft. Homeowners of a certain age and sex who do not want to work as security guards will be locked up in the storage room of the community center.

Now there’s a problem. Because the association has taken some homeowners out of the customary work force, those people are not available for doing jobs for other homeowners, who must pay more to contract services. This is one of several paths that leads to inflation. To combat that, the association sets price controls and limits the goods that homeowners can purchase. After a while, the outsiders are driven off and the size of the security force returns to its former levels.

Now all the extra Money that the association printed to pay for the security force has to be destroyed. As homeowners pay their dues, the association retires some of the money and shrinks the Money supply. However, there is a time lag, and prices rise sharply (Note #6).

Over the ensuing decades, there are other emergencies – flooding after several days of rain, a sinkhole that formed under one of the roadways, and a sewer system that needed to be dug up and replaced. The association printed more Debt to cover some of the costs, but it had to print more Money to pay for the balance of repairs. Because the rise in the supply of Money was a trade for goods and services, inflation remained tame.

There didn’t seem to be any negatives to printing more Money, so the homeowners passed a resolution requiring that the association print and pay Money to homeowners who were down on their luck. These were active transfers – payments to homeowners without a trade in goods and services and without some offsetting payment by the other homeowners.

So far in our story we have several elements that correspond with the real world: currency, taxes, social insurance, the creation of money and debt and the need to pay for defense and catastrophic events. Let’s continue the story.

With the newly printed Money, those poorer homeowners could now buy more goods and services. The increased demand caused prices to rise and all the homeowners began to complain. Realizing their mistake, they voted on an austerity program of higher homeowner fees and lower active transfers to poorer homeowners.

Because homeowners had to pay higher fees, they didn’t have enough extra Money to hire other services. Some residents approached the association and offered to repair fences and other maintenance jobs, but the association said no; it was on an austerity program and cutting expenses. Some residents simply couldn’t pay their fees and the problem grew. The association now found that it received less Money than before the higher fees and Austerity program. It cut expenses even more, but this only aggravated the problem.

Finally, the association ended their Austerity program. They printed more Money and hired homeowners to make repairs. Several homeowners came up with a different idea. There is another housing development called the Forners a few miles away. They are poorer and produce some goods for a lower price. The homeowners can buy stuff from the Forners and save money. There are three advantages to this program:

- Things bought from the Forners are cheaper.

- Because the homeowners will not be using local resources, there will be less upward pressure on prices.

- The homeowners will pay the association for the goods bought from the Forners and the association will pay the Forners community with Debt, not Money. Since it is the creation of Money that led to higher prices, this arrangement will help keep inflation stable.

As the homeowners buy more and more stuff from the Forners, the money supply remains stable or decreases. After several years, homeowners are buying too much stuff from the Forners and there is less work available in the community. As homeowners cannot find work, they again fall behind in paying their monthly fees.

Several of those in the association realize that they don’t have enough Money to go around in the community. There is a lot to do, and the homeowners draw up a wish list: repairs to the roads and helping older homeowners with shopping or repairs around their home are suggested first. A person who is out of work offers to lead tours and explain the biology of trees for schoolchildren. The common lot near the clubhouse could use some flowers, another homeowner suggests. I could use a babysitter more often, one suggests, and everyone nods in agreement. I could teach a personal finance class, a homeowner offers. Another offers to read to homeowners with bad eyesight and be a walking companion to those who want to get more exercise.

Everyone who contributes to the welfare of the community gets paid with Money that is created by the association. What should we call the program? One person suggests “The Paid Volunteer Program,” and some people like that. Another suggests, “The Job Guarantee Program” and everyone likes that name so that’s what they called it (Note #7).

So far in this story we have two key elements of an organized society:

- Money – a paper currency created by the homeowner association.

- Debt – the amount the association owes to homeowners (domestic) and the Forners (international).

Next week I hope to continue this story with a transition to a digital currency, banks and loans.

//////////////////////

Notes:

- In 2016, the top 20% of incomes with more than $200K in income, earned more than 2/3rds of the total interest and dividends. IRS data, Table 1.4

- In 2018 dollars, the publicly held debt of the Federal government was $4 trillion in 1990, and $16 trillion now. In 2018 dollars, interest expense was $500B in 1990, and is $600B now.

- In David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5000 Years, there is no record of any early societies that had a barter system. They had a ledger or money system from the start.

- In the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith – the “father” of economics – defined money as that which has no other value than to be exchanged for a good. This essential characteristic makes money unique and differentiates paper money from other mediums of exchange like gold and silver.

- An easy memory trick to distinguish inflation from deflation. INflation = Increase in prices. DEflation = DEcrease.

- The account of the increased force of security guards – and its effect on prices and regulations – is the simple story of money and inflation during WW2 and the years immediately following. The process of rebalancing the money supply by the central bank is difficult. Monetary policy during the 1950s was a chief contributor to four recessions in less than 15 years following the war.

- A Job Guarantee program is a key aspect of Modern Monetary Theory.