“It takes a lot of time to be a genius. You have to sit around so much, doing nothing, really doing nothing.”― Gertrude Stein

September 16, 2018

by Steve Stofka

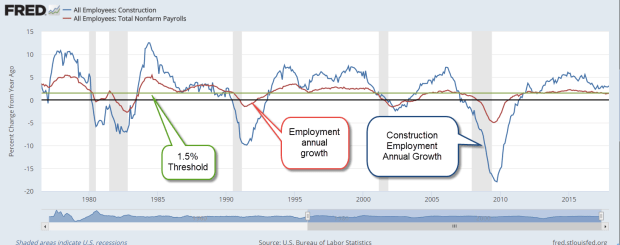

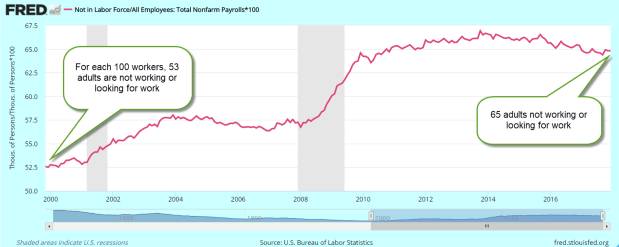

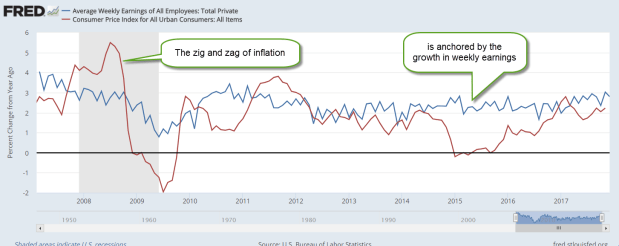

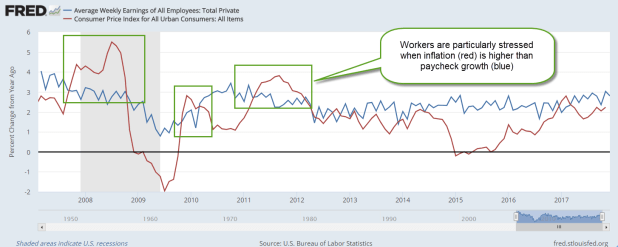

As the U.S. market grinds higher, emerging markets are in bear territory, off 20% from their highs at the beginning of the year and selling at 2007 prices. After nine years of recovery, the U.S. economy is in the late stages of the cycle. Warnings of an impending market fall will come true at some point. If the market falls in 2020, those who called for a fall in 2014 will say, “See, I called it. Buy my book.” This year, hedge funds, the smart money, have underperformed index funds, the dumb money. For several years, passive index funds have outperformed active fund managers, a phenomenon that some warn will lead to a catastrophic meltdown when it happens.

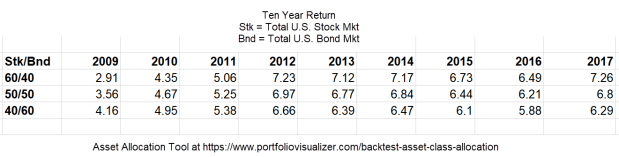

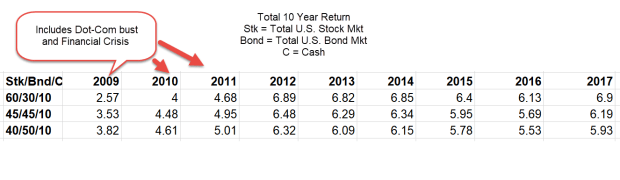

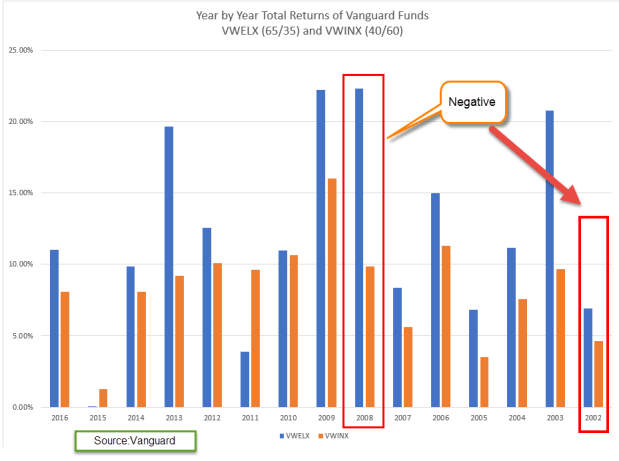

For the average retail investor, it is difficult to beat buy and hold. An investor who bought the SP500 index 25 years ago would have earned 9% per year in price appreciation alone. Adding in dividends would have raised the annual gain to 9.58%. That is what is called a “Buy and Hold” (BnH) strategy. It’s not a strategy. It’s a strategy of no strategy, and yet it is surprisingly difficult to consistently beat a no-brainer no-strategy like BnH over several decades. The stock market earned this while riding through two downturns that erased half of the market’s value. Even a middle of the road strategy of 60% stocks and 40% bonds earned 8.3% annually during the same period.

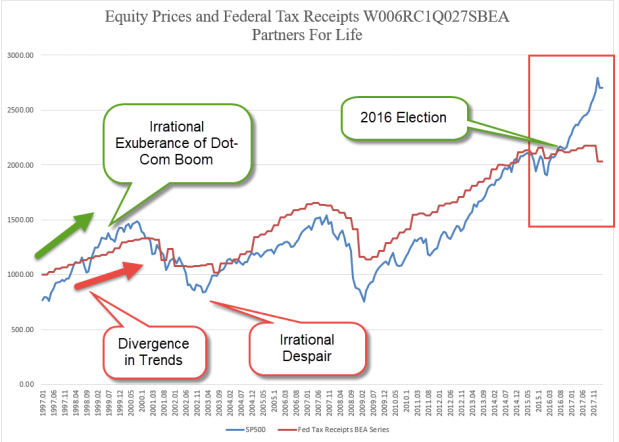

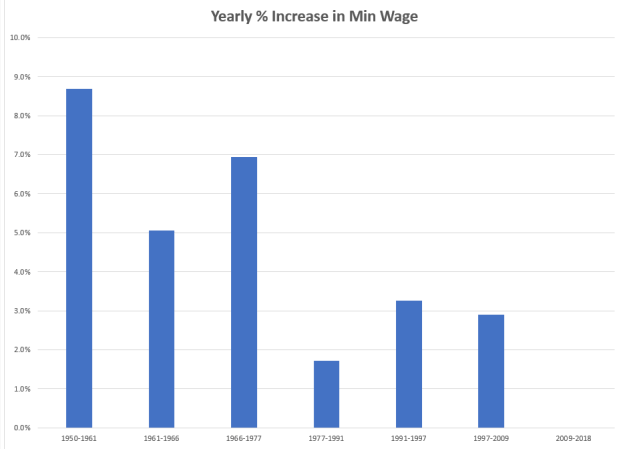

Traders develop rules that work in one decade, but don’t work in the next. A strategy that worked well in the years 1998-2007 didn’t work well in the period 2008-2017. Why? Because they were two different time periods, with different events and circumstances (Note #1).

Here’s a rule that could have earned an investor twenty – yes, twenty – times BnH in the period from 1960-1993. The rule did not work in any timing frame other than daily. Each morning at the open, buy the SP500 index if the previous day was up, sell if it was down. Huge profits even after trading costs (Note #2). 1993 – 2018? It was a losing strategy. It would have been better to do exactly the opposite – sell after an up day and buy after a down day.

Every year thousands of people will shell out good money for a winning strategy that promises to best the market. Most strategies don’t beat the market consistently. Those that do are guarded like the nation’s gold at Fort Knox and are not shared. For the rest of us, the winning strategy is a few rules: save money and invest in a balanced portfolio that is appropriate for our age and needs in the next five years.

///////////////////////////

Notes:

- From 1998-2007, an emerging market index fund (VEIEX) earned 15.08% annually. From 2008-2017, that same fund earned 1.13% annually. For the combined twenty-year period, the annual gain was 7.87%.

- Until the SPY exchange traded product was created in 1993, there was no product that enabled a retail investor to trade daily and frequently. Mutual funds that mimicked the index restricted the frequency of trades. I used the daily SP500 index numbers as though there had been such a product created in 1960.