April 3, 2016

Normally we do not include the value of our home in our portfolio. A few weeks ago I suggested an alternative: including a home value based on it’s imputed cash flows. Let’s look again at the implied income and expense flows from owning a home as a way of building a budget. The Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau take that flow approach, called Owner Equivalent Rent (OER), when constructing the CPI, and homeowners are well advised to adopt this perspective. Why?

1) By regarding the house as an asset generating flows, it may provide some emotional detachment from the house, a sometimes difficult chore when a couple has lived in the home a long time, perhaps raised a family, etc.

2) It focuses a homeowner on the monthly income and rent expense connected with their home ownership. It asks a homeowner to visualize themselves separately as asset owner and home renter. It is easy for homeowners to think of a mortgage free home as an almost free place to live. It’s not.

3) Provides realistic budgeting for older people on fixed incomes. Some financial planners recommend spending no more than 25% of income on housing in order to leave room for rising medical expenses. Some use a 33% figure if most of the income is net and not taxed. For this article, I’ll compromise and use 30% as a recommended housing share of the budget.

A fully paid for home that would rent for $2000 is an investment that generates an implied $1400 in income per month, using a 70% net multiplier as I did in my previous post. Our net expense of $600 a month includes home insurance, property taxes, maintenance and minor repairs, as well as an allowance for periodic repairs like a new roof, and capital improvements.

Using the 30% rule, some people might think that their housing expense was within prudent budget guidelines as long as their income was more than $2000 a month. $600 / $2000 is 30%.

However, let’s separate the roles involved in home ownership. The renter pays $2000 a month, implying that this renter needs $6700 a month in income to stay within the recommended 30% share of the budget for housing expense. The owner receives $1400 in net income a month, leaving a balance of $5300 in income needed to stay within the 30% budget recommendation. $6700 – $1400 = $5300. Some readers may be scratching their heads. Using the first method – actual expenses – a homeowner would need only $2000 per month income to stay within recommended guidelines. Using the second method of separating the owner and renter roles, a homeowner would need $5300 a month income. A huge difference!

Let’s say that a couple is getting $5000 a month from Social Security, pension and other investment income. Using the second method, this couple is $300 below the prudent budget recommendation of 30% for housing expense. That couple may make no changes but now they understand that they have chosen to spend a bit more on their housing needs each month. If – or when – rising medical expenses prompt them to revisit their budget choices, they can do so in the full understanding that their housing expenses have been over the recommended budget share.

This second method may prompt us to look anew at our choices. Depending on our needs and changing circumstances, do we want to spend $2000 a month for a house to live in? Perhaps we no longer need as much space. Perhaps we could get a suitable apartment or townhome for $1400? Should we move? Perhaps yes, perhaps no. Separating the dual roles of owner and renter involved in owning a home, we can make ourselves more aware of the implied cost of our decision to stay in the house. A house may be a treasure house of memories but it is also an asset. Assets must generate cash flows which cover living expenses that grow with the passage of time.

/////////////////////

The Thrivers and Strugglers

“Bravo to MacKenzie. When she was born, she chose married, white, well-educated parents who live in an affluent, mostly white neighborhood with great public schools.”

In a recent report published by the Federal Reserve Bank at St. Louis, the authors found that four demographic characteristics were the chief factors for financial wealth and security: 1) age; 2) birth year; 3) education; 4) race/ethnicity.

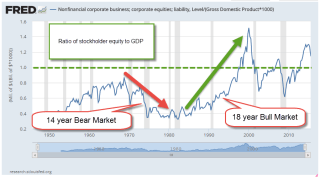

While it is no surpise that our wealth grows as we age, readers might be puzzled to learn that the year of our birth has an important influence on our accumulation of wealth. Those who came of age during the depression had a harder time building wealth than those who reached adulthood in the 1980s.

Ingenuity, dedication, persistence and effort are determinants of wealth but we should not forget that the leading causes of wealth accumulation in a large population are mostly accidental. It is a humbling realization that should make all of us hate statistics! We want to believe that success is all due to our hard work, genius and determination.

//////////////////////

Employment

March’s job gains of 215K met expectations, while the unemployment rate ticked up a notch, an encouraging sign. Those on the margins are feeling more confident about finding a job and have started actively searching for work. The number of discouraged workers has declined 20% in the past 12 months.

Employers continue to add construction jobs, but as a percent of the workforce there is more healing still to be done.

The y-o-y growth in the core workforce, aged 25-54, continues to edge up toward 1.5%, a healthly level it last cleared in the spring of last year.

The Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI) maintained by the Federal Reserve is a composite of about 20 employment indicators that the Fed uses to gauge the overall strength and direction of the labor market. The March reading won’t be available for a couple of weeks, but the February reading was -2.4%.

Inflation is below the Fed’s 2% target, wage gains have been minimal, and although employment gains remain relatively strong, there is little evidence to compel Chairwoman Yellen and the rate setting committee (FOMC) to maintain a hard line on raising interest rates in the coming months. I’m sure Ms. Yellen would like to get Fed Funds rate to at least a .5% (.62% actual) level so that the Fed has some ability to lower them again if the economy shows signs of weakening. Earlier this year the goal was to have at least a 1% rate by the end of 2016 but the data has lessened the urgency in reaching that goal.

ISM will release the rest of their Purchasing Manager’s Index next week and I will update the CWPI in my next blog. I will be looking for an uptick in new orders and employment. Manufacturing lost almost 30,000 jobs this past month – most of that loss in durable goods. Let’s see if the services sector can offset that weakness.

///////////////////////////

Company Earnings

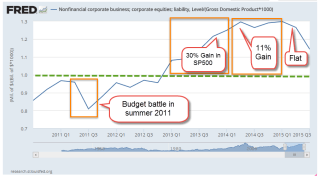

Quarterly earnings season is soon upon us and Fact Set reports that earnings for the first quarter are estimated to be down almost 10% from this quarter a year ago. The ten year chart of forward earnings estimates and the price of the SP500 indicates that prices overestimated earnings growth and has traded in a range for the past year. March’s closing price was still below the close of February 2015. Falling oil prices have taken a shark bite out of earnings for the big oil giants like Exxon and Chevron and this has dragged down earnings growth for the entire SP500 index.