June 9, 2024

by Stephen Stofka

This week’s letter continues my exploration of the role of expectations. They coordinate the supply, demand and price relationships that form the web of our economic and financial lives. They shape our voting patterns, and alter our behavior in interactions with others. If we expect a police officer to be hostile, we are defensive. That reaction will affect the behavior of the officer, increasing the chance that the encounter will be hostile. Expectations cause us to behave in ways that confirm and amplify our expectations, aggravating undesirable circumstances.

Expectations and yearnings act symbiotically within us but there is a distinction between the two. Expectations are a calculation; yearnings are a desire. “I think that” is an expectation. “I hope that” is a yearning. A woman may yearn to have a child, but she expects to have a child within a period of time. A yearning knows no time or logic. We expect a certain range of compensation for the type of work we do, our skill level and experience. Business coaches encourage people to visualize and enhance their good attributes to raise those expectations. Business owners expect their capital to earn a certain percentage of profit as compensation for the risk, planning and skill that a successful business requires.

Consumers expect a certain range of prices for many frequently bought goods and services. The price of meat may be more or less than average in a week, but the price will not be $100 a pound for ground beef. We may have no price anchor for infrequent purchases like replacing a hot water heater. A few hundred dollars or a few thousand? A search in a browser can help with an average price of approximately $2100 to help a homeowner evaluate quotes from a plumbing contractor.

In the U.S., the pricing of medical care is treated as a catastrophic event like a house fire. The connection between price and medical care has been cut so that patients may not know beforehand the price of a procedure. A browser search for the cost of a colonoscopy indicates an average cost of $2200, close to that of a hot water heater, coincidentally, but medical providers do not quote a price. Prices are negotiated between health insurance companies and a network of medical providers. The negotiated price may be a fifth of the stated list price. If patients have health insurance, the only price visible to them is a co-pay. The prospect of higher medical costs next year does not incentivize us to seek care now at a lower price. Colonoscopy prices going up soon? Let me book one now! However, as costs increase, workers negotiate for better benefit packages that cover the anticipated higher costs.

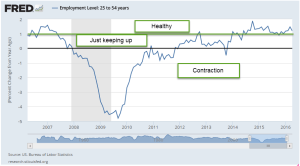

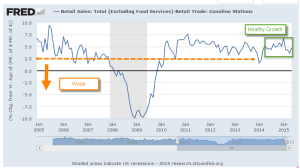

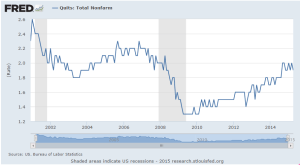

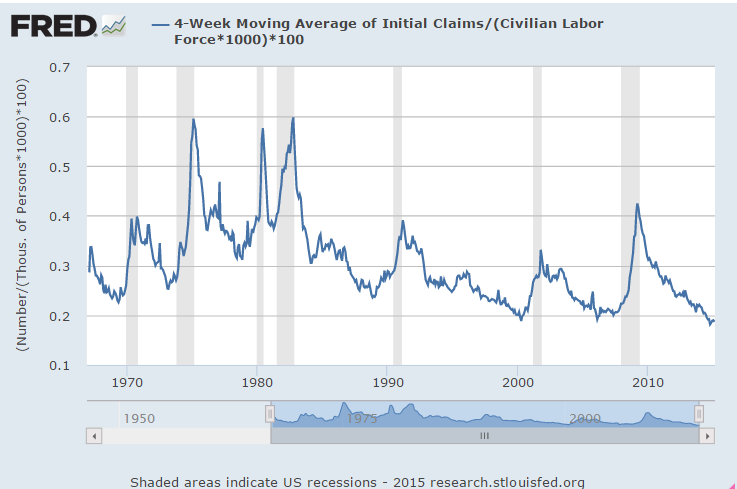

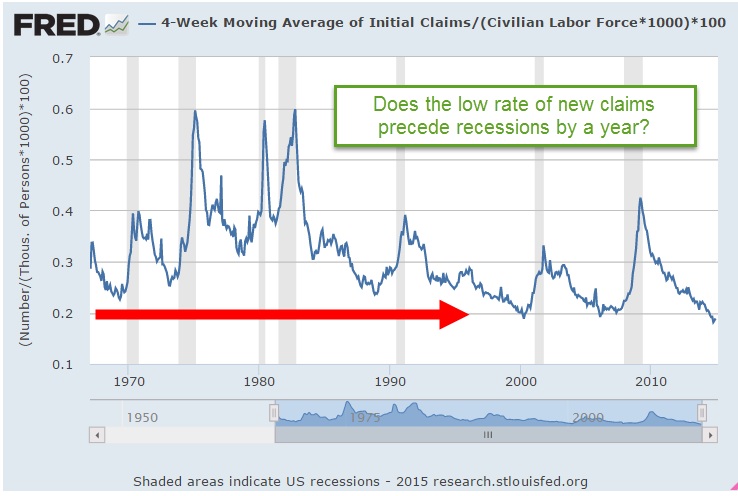

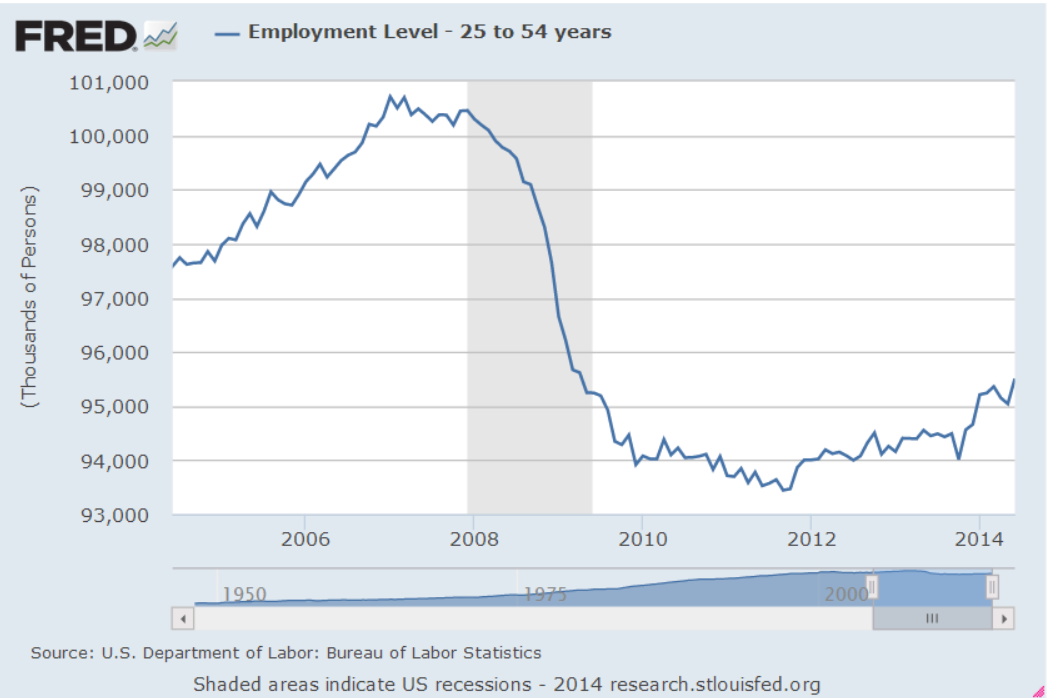

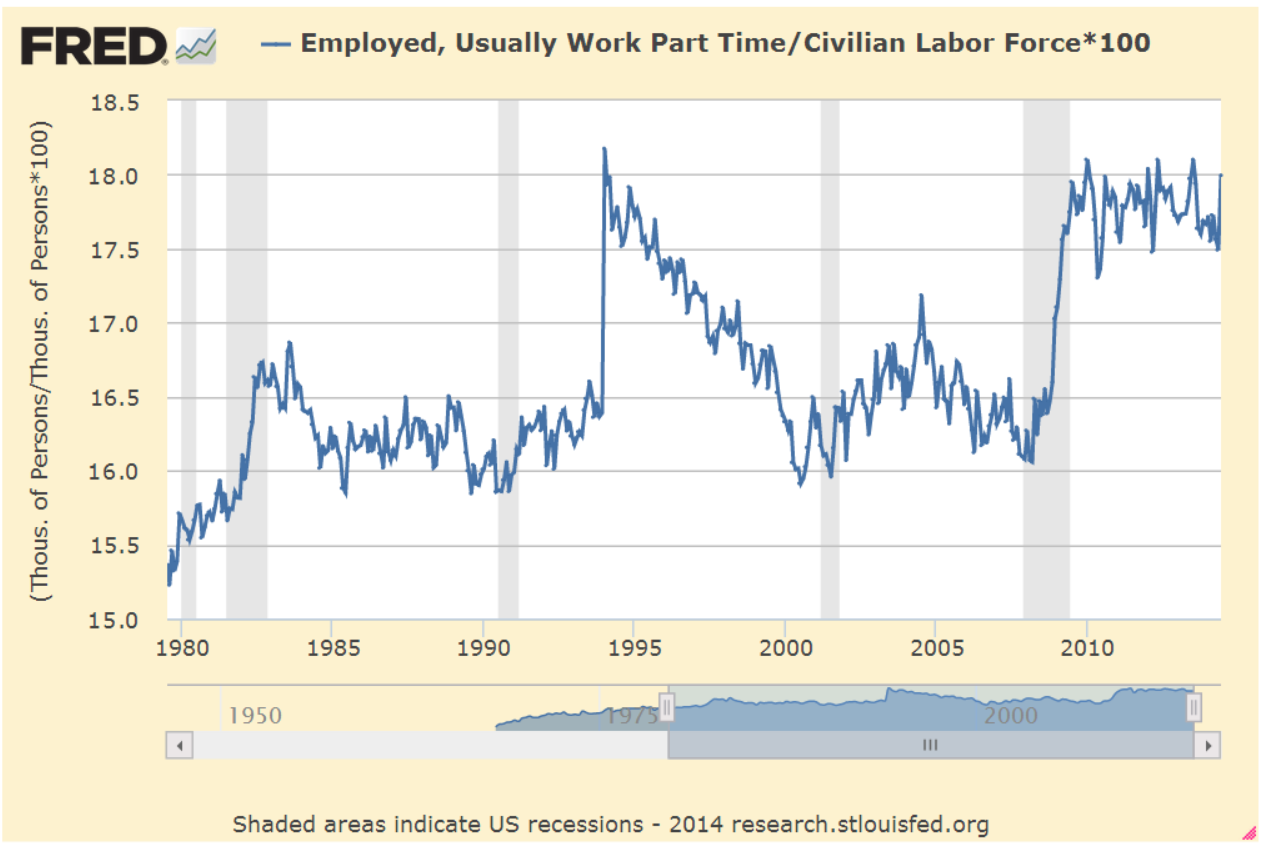

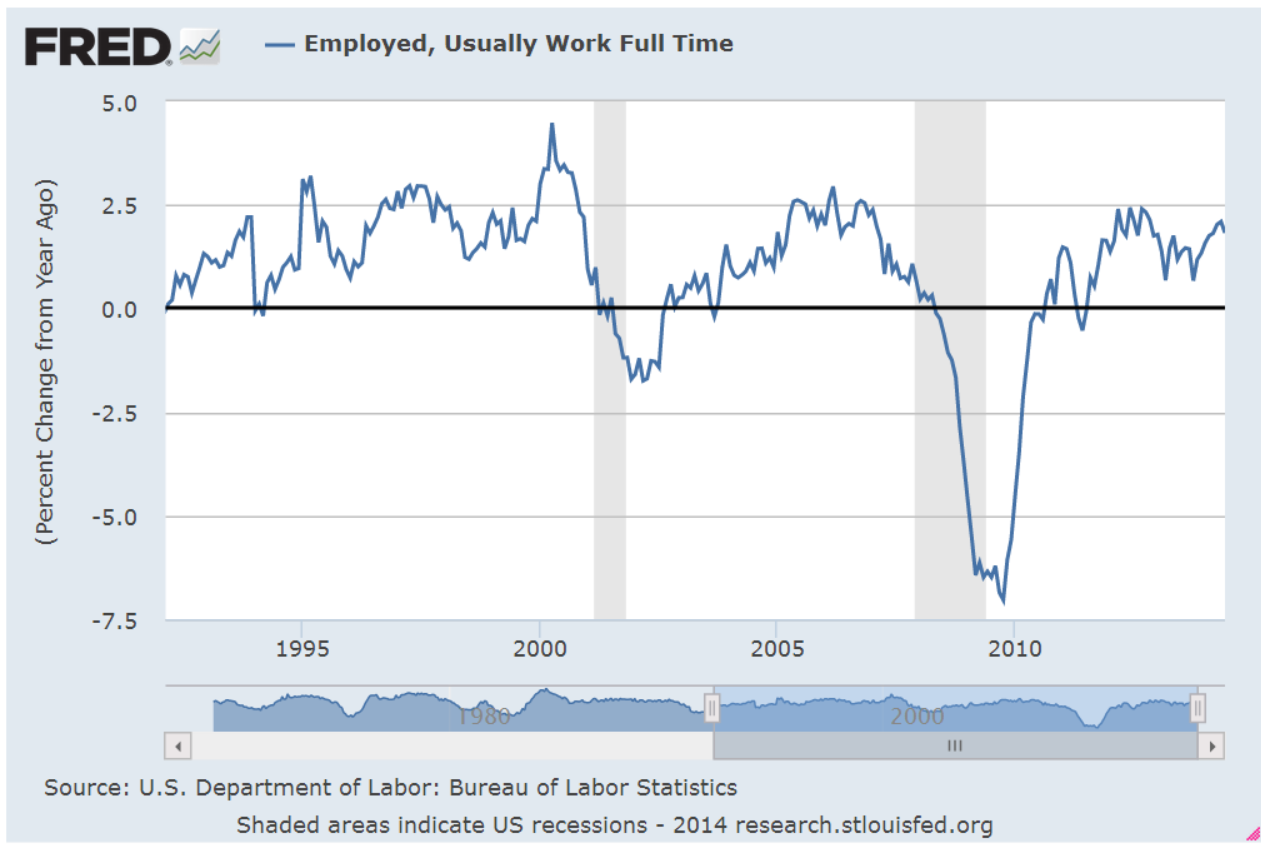

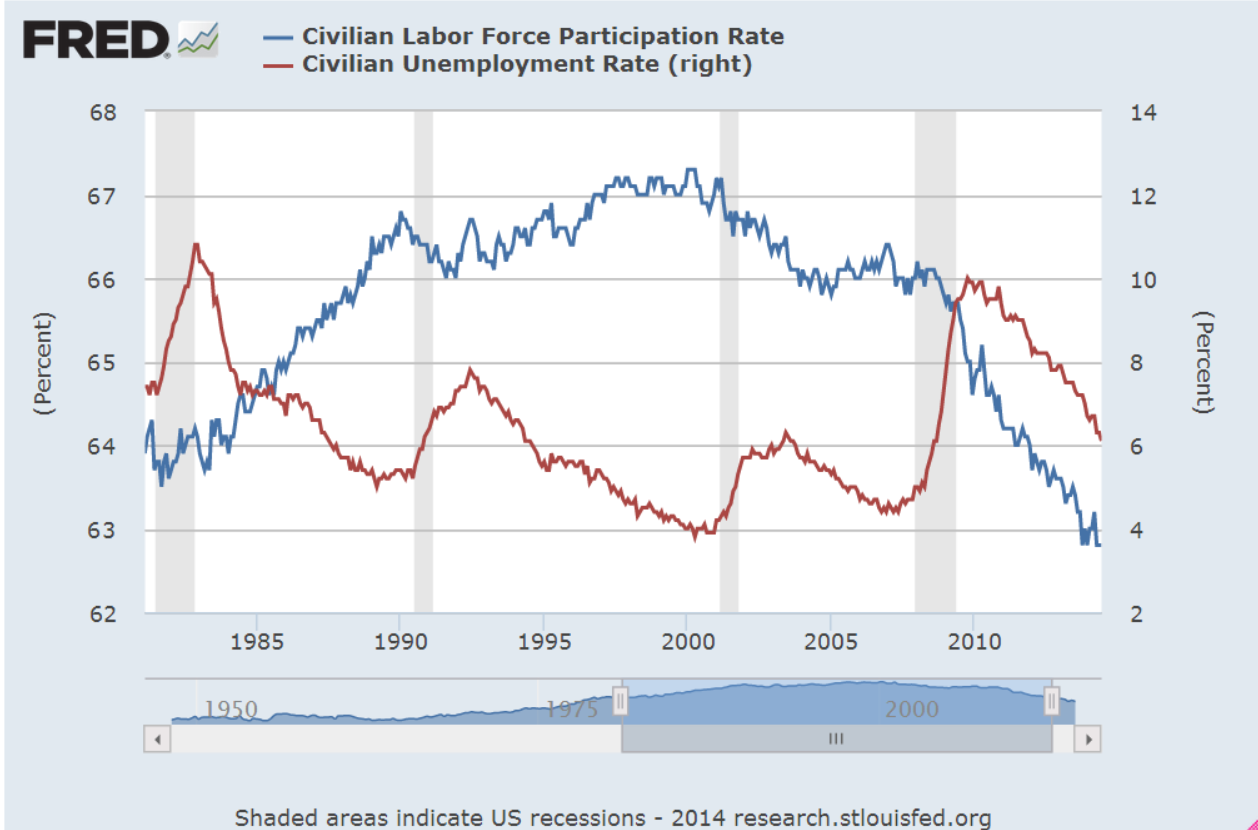

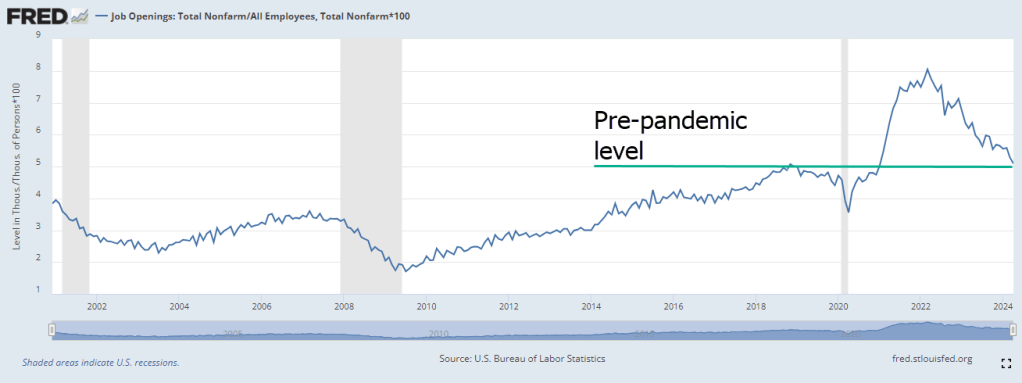

In our economy, workers play a dual role of producer and consumer. The monthly labor report and retail sales report captures the importance of these roles, and the release of these reports move markets. In the core labor force age range of 25 to 54, four out of five people are working or looking for work, according to the latest labor report. The largest generation in this demographic are the Millennials, born between 1981 and 1996. They produce the most and buy the most so their expectations steer the economy. Job openings as a percent of total employment indicate a historically robust labor market. Recent reports indicate that openings are returning to pre-pandemic levels.

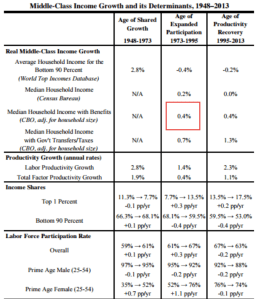

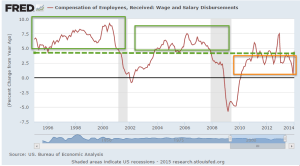

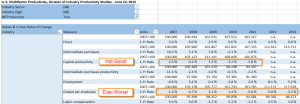

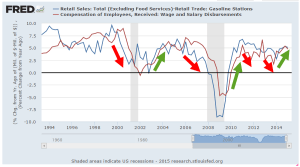

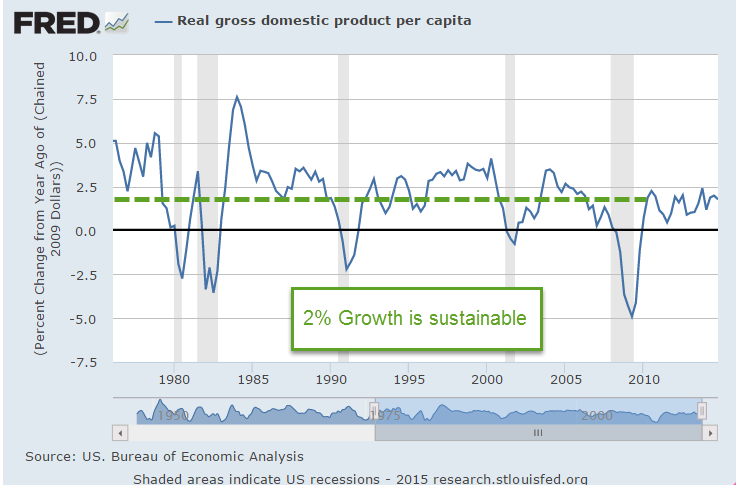

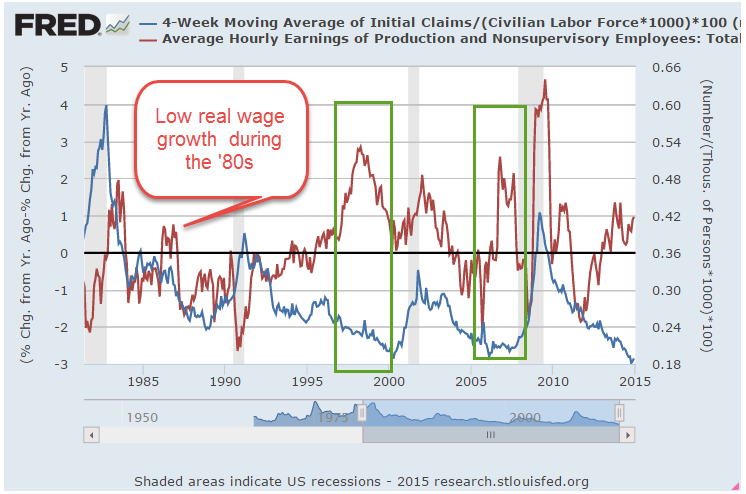

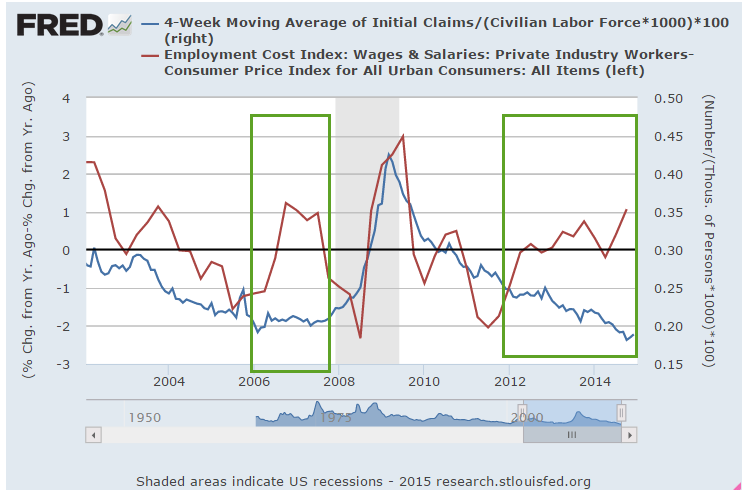

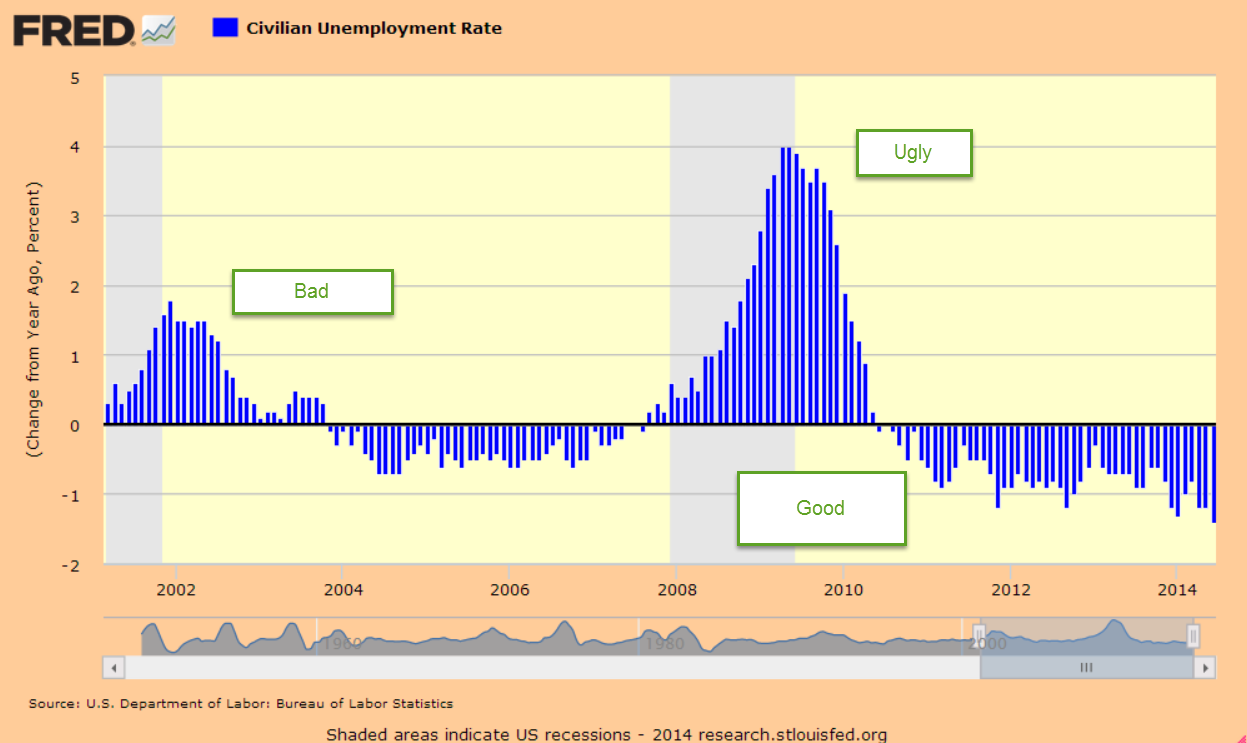

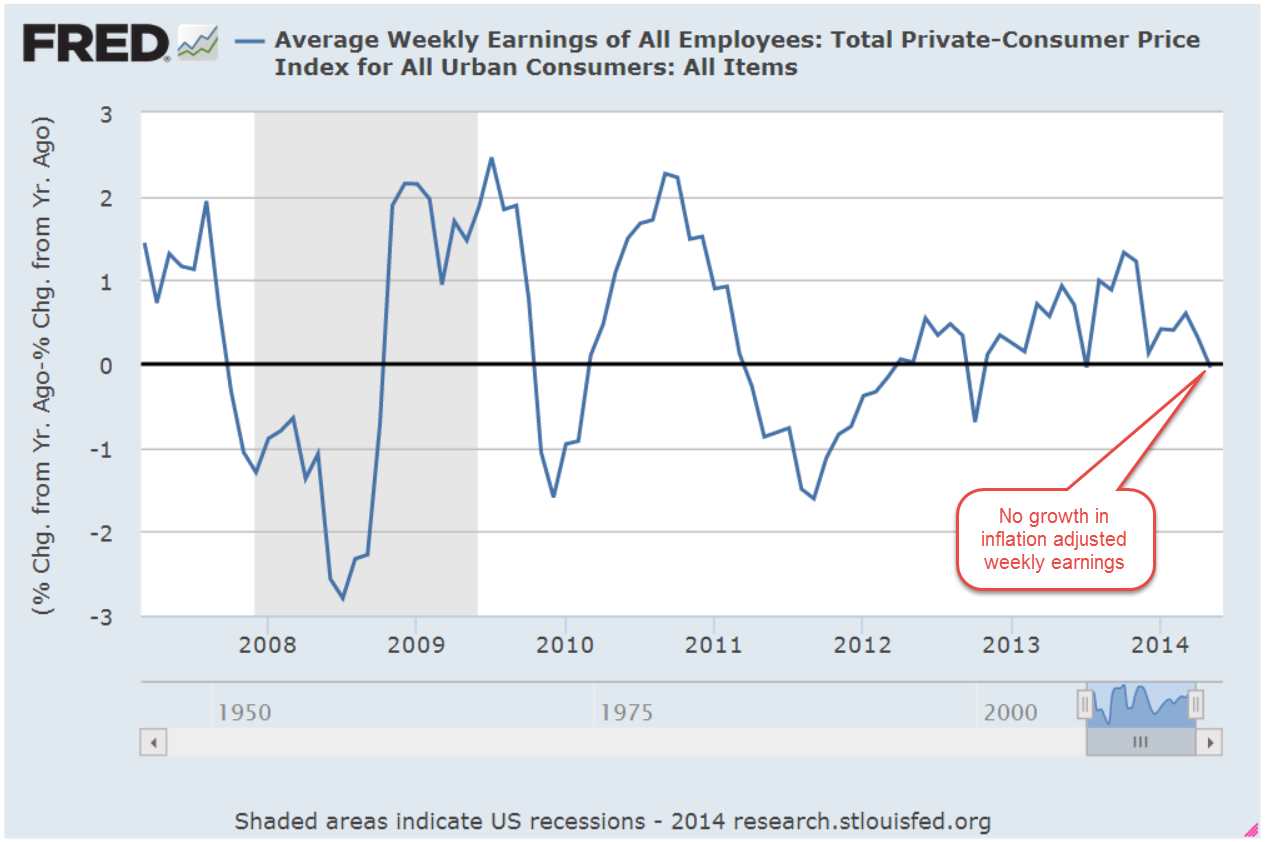

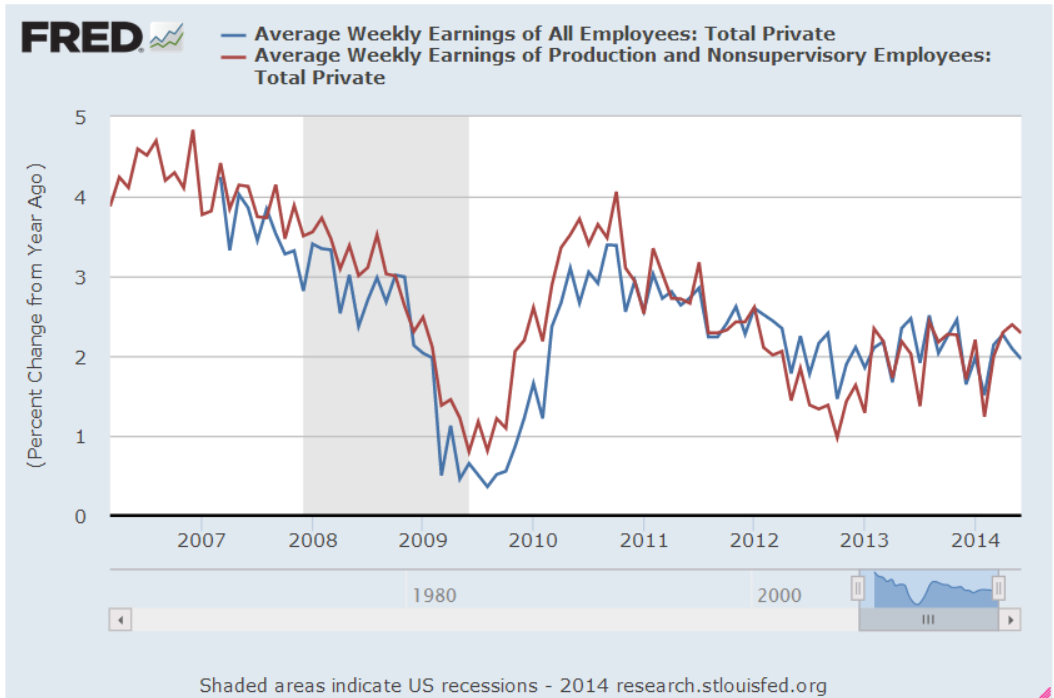

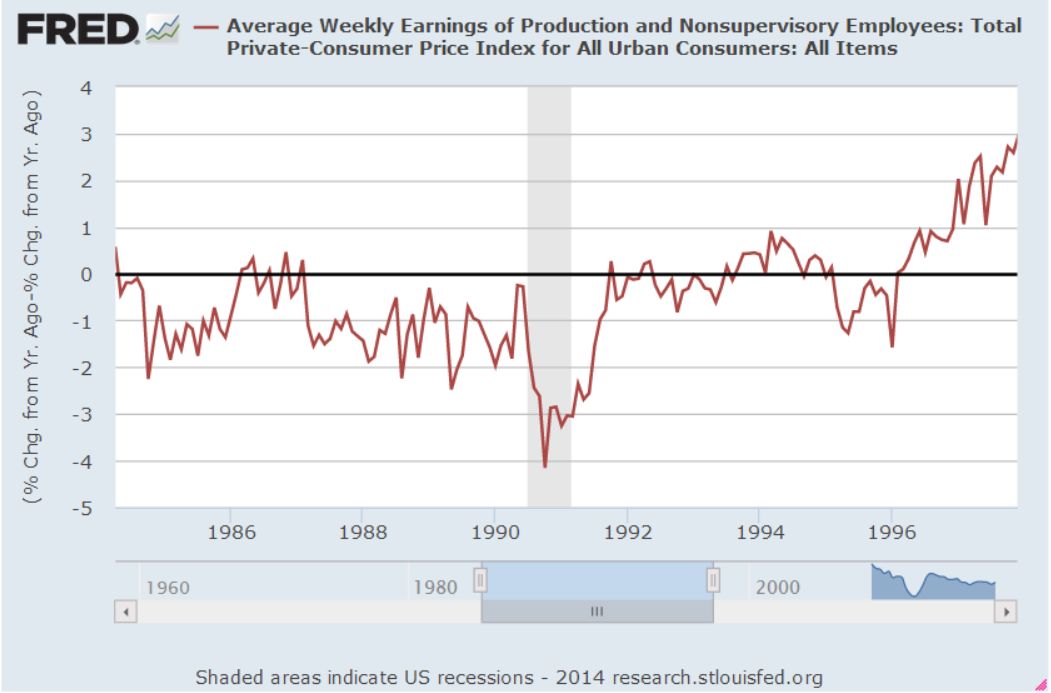

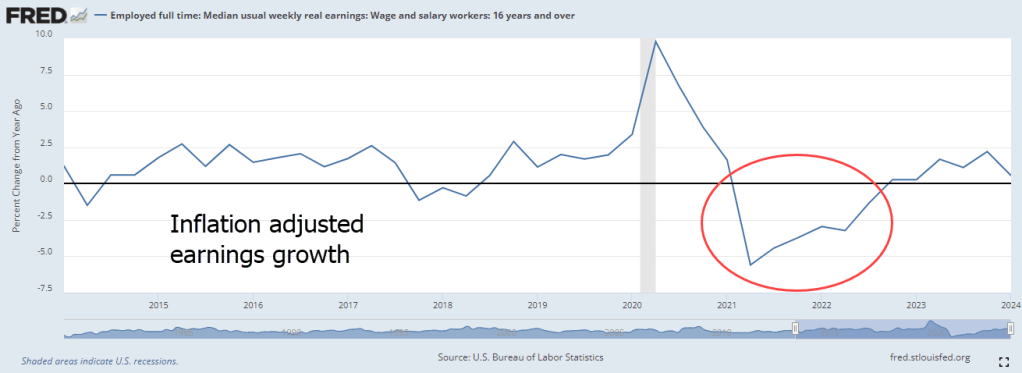

Despite the strong demand for labor, post-pandemic inflation has taken a bite out of gains in median earnings. Biden assumed office as earnings gains turned negative. Despite legislation meant to promote investment and support the labor market – the Inflation Reduction Act – the decline in real earnings did not turn positive until 2023.

Real earnings equals real purchasing power. Late Millennials reaching their early thirties expected to be able to settle down and buy a house. Older Millennials in their forties who expected to trade up to a different home are frustrated by high home prices and interest rates. Political power in our system is captured by the interests of older voters, particularly the Boomers. Less than one out of four in this generation is working (FRED series here). They want to reduce their tax costs, and preserve or enhance the government benefits they feel they have earned after a lifetime of working.

This week, David Leonhardt, editor of the N.Y. Times Morning Newsletter, pointed out a poll indicating strong support for many policies initiated by the Biden administration. Most of the public’s attention is directed to controversial issues like immigration, the war in Gaza and American support for Ukraine in their continuing war against Russia’s invasion. The pandemic focused the public’s attention on Trump’s chaotic governing style. His behavior defied expectations and his supporters became accustomed to excusing or rationalizing his actions. A majority voted for Biden as a return to normalcy in the recovery from the pandemic.

People vote their expectations, and those expectations strongly influence voters’ assessments of the economy even before a candidate has taken office. A candidate needs to offer a clear set of new expectations that manifest the yearnings of a majority of voters. Has either candidate made the connection between voter expectations and yearnings? Next week I will look more closely at the political aspect of expectations.

////////////////

Photo by Jan Tinneberg on Unsplash

Keywords: prices, growth, earnings, inflation