August 17, 2014

This week I’ll take a look at the latest retail sales figures, a less publicized volatility indicator, a comparison of BLS projections of the Labor Force Participation Rate, and the adding up of personal savings.

**********************

Retail Sales

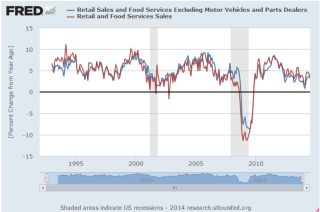

Two economic reports which have a major influence on the market’s mood are the monthly employment and retail sales reports. After a disappointing but healthy employment report this month, July’s retail sales numbers were disappointing, showing no growth for the second month in a row. The year-over-year growth is 3.7%, which, after inflation, is about 1.5% real growth. Excluding auto sales (blue line in the graph below), sales growth is 3.1, or about 1% real growth, the same as population growth.

As we can see in the graph below, the growth in auto sales has kicked in an additional 1/2% in growth during this recovery period. Total growth has been weakening for the past two years despite strong growth in auto sales, a sign of an underlying lack of consumer power.

Real disposable income rebounded in the first six months of this year after negative growth in the last half of 2013 but there does not seem to be a corresponding surge in sales.

*****************************

Labor Force Projections

While we are on the subject of telling the future…

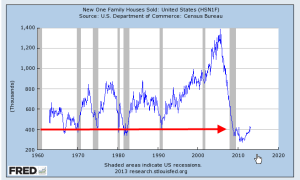

All we need are 8 million more workers in the next two years to meet Labor Force projections made in 2007 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 8 million / 24 months = 300,000 a month net jobs gained. Hmmm…probably not. In 2007, the BLS forecast slowing growth in the labor force in the decade 2006 – 2016. Turned out it was a lot slower. Estimates then for 2016 projected a total of 164 million employed and unemployed. In July 2014, the BLS put the current figure at 156 million employed. The Great, or at least Big, Recession caused the BLS to revise their forecast a number of times. The current estimate has a target date of 2022 to hit the magic 164 million. In other words, we are 6 years behind schedule.

The Participation Rate is the ratio of the Civilian Labor Force to the Civilian Non-Institutional Population aged 16 and above. The equation might be written: (E + UI) / A = PR, where E = Employed, UI = Unemployed and Actively Looking for Work, and A = people older than 16 who are not in the military or in prison or in some institution that would prevent them from making a choice whether to work or not. As people – the A divisor in the equation – live longer, the participation rate gets lower. It ain’t rocket science, it’s math, as baseball legend Yogi Berra might have said.

The Participation Rate started rising in the 1970s as more women entered the work force, then peaked in the years 1997 – 2000. Prior to the recession of 2001, the pattern of the participation rate was predictable, declining during an economic downturn, then rising again as the economy recovered. The recovery after the recession of 2001 was different. The rate continued to decline even as the economy strengthened.

In 2007, the BLS expected further declines in the rate from a historically high 67% in 2000 to 65.5% in 2016. In 2012, the rate stood at 63.7%. Current projections from the BLS estimate that the rate will drop to 61.6% by 2022.

Much of the decline in the participation rate was attributed to demographic causes in the 2007 BLS projections:

“Age, sex, race, and ethnicity are among the main factors responsible for the changes in the labor force participation rate.” (Pg. 38)

Comparing estimates by some smart and well trained people over a number of years should remind us that it is extremely difficult to predict the future. We may mislead ourselves into thinking that we are better than average predictors. Our jobs may seem fairly secure until they are not; a 5 year CD will get about 5 – 6% until it doesn’t; the stock market will sell for about 15x earnings until it doesn’t; bonds are safe until they’re not.

The richest people got rich and stay rich because they know how unpredictable the world really is. They hire managers to shield them – hopefully – from that unpredictability. They fund political campaigns to provide additional insurance against the willy-nilly of public policy. They fight for government subsidies to provide a safety cushion, to offset portfolio losses and mitigate risk. What do many of us who are not so rich do to insure ourselves against volatility? Put our money in a safe place like a savings account or CD. In real purchasing power, that costs us 1 – 2%, the difference between inflation and the paltry interest rate paid on those insured accounts. In addition, we can pay a hidden “insurance” fee of 4% in foregone returns by being out of the stock and bond markets. We stay safe – and not-rich. Rich people manage to stay safe – and rich – by not doing what the not-rich people do to stay safe. Yogi Berra couldn’t have said it better.

***************************

China

For you China watchers out there, Bloomberg economists have compiled a monetary index from several key factors of monetary policy. After hovering near decade lows, China’s central bank has considerably loosened lending in the past two months. The chart shows the huge influx of monetary stimulus that China provided in 2009 and 2010 as the developed world tried to climb up out of the pit of the world wide financial crisis.

The tug of war in China is the same as in many countries. Politicians want growth. Central banks worry about inflation. The rise in this index indicates that the central bank is either 1) bowing to political pressure, or 2) feels that inflationary pressures are low enough that they can afford to loosen the monetary reins. As is often the case with monetary policy, it is probably some combination of the two.

**************************

Personal Savings Rate

Over the past two decades, economists have noted the low level of savings by American workers. While economists debate methodologies and implications, politicians crank up their spin machines. More conservative politicians cite the low savings rate as an indication of a lack of personal responsibilty. As workers become ever more dependent on government programs, they do not feel the need to save. Over on the left side of the political aisle, liberals cite the low savings rate as a sign of the growing divide between the middle class and the rich. Many families can not afford to save for a house, or their retirement, or put aside money for their children’s education. We need more programs to correct the economic inequalities, they say.

While there might be some truth in both viewpoints, the plain fact is that the Personal Savings Rate doesn’t measure savings as most of us understand the term. A more accurate title for what the government calls a savings rate would be “Delayed Consumption Rate.” The methodology used by the Dept. of Commerce counts whatever is not spent by consumers as savings. “To consume now or consume later, that is the question.”

If a worker puts money into a 401K each month, the employer’s matching contribution is not counted. If a consumer saves up for a down payment for a house, that is included in savings. When she takes money out of savings to buy the house, that is a negative savings. The house has no value in the “savings” calculation. Many investors have a large part of their savings in mutual funds through personal accounts and 401K plans at work. Capital gains in those funds are not counted as savings. (Federal Reserve paper) In short, it is a poor metric of the aggregate behavior of consumers. Some economists will point out that the savings rate indicates a level of demand that consumers have in reserve but because a significant portion of saved income is not counted, it fails to properly account for that either.

************************

Volatility – A section for mid-term traders

No one can accurately predict the future but we can examine the guesses that people make about the future. In his 2004 book The Wisdom of Crowds (excerpt here) James Surowiecki relates a number of studies in which people are asked to guess answers to intractable problems, like how many jelly beans are in a jar. As would be expected, respondents rarely get it right. The surprising find was that the average of guesses was remarkably close to the correct answer.

Through the use of option contracts, millions of traders try to guess the market’s direction or insure themselves against a change in price trend. A popular and often quoted gauge of the fear in the market is the VIX, a statistical measure of the implied volatility of option contracts that expire in the next thirty days. When this fear index is below 20, it indicates that traders do not anticipate abrupt changes in stock prices.

Less mentioned is the 3 month fear index, VXV (comparison from CBOE). Because of its longer time horizon, it might more properly be called a worry index. Many casual investors have neither the time, inclination or resources to digest and analyze the many economic and financial conditions that impact the market. So what could be easier than taking a cue from traders preoccupied with the market? Below is a historical chart of the 3 month volatility index.

Historically, when this gauge has crossed above the 20 mark for a couple of weeks, it indicates an elevated state of worry among traders. The 48 month or 4 year average of the index is 19.76. Currently, we are at a particularly tranquil level of 14.42.

When traders get really spooked, the 10 day average of this anxiety index will climb to nosebleed heights as it did during the financial crisis. As the market calms down, the average will drift back into the 20s range, an opportunity for a mid-term trader to get cautiously back into the water, alert for any reversal of sentiment.

*********************

Takeaways

Retail sales have flat-lined this summer but y-o-y gains are respectable. So-so income growth constrains many consumers. The 3 month volatility index is a quick and dirty summary of the mid-term anxiety level of traders. A comparison of BLS labor force projections shows the difficulty of making accurate predictions. The personal savings rate under-counts savings.