October 23, 2016

About 30 years ago, after a series of social security and income tax increases in the early ’80s, I had a spirited discussion with my dad about what I thought was a transfer of money from my generation to his. Extremely low interest rates for the past eight years have reversed that process. Millions of older Americans who have saved throughout their working years are getting paid almost nothing on that part of their savings held in safe accounts. Older Americans take less risk with their savings and it is precisely these safer investments that have suffered under the ZIRP, or Zero Interest Rate Policy, of the Federal Reserve. That money is implicitly transferred to younger generations who pay less interest for their auto loans, for their mortgages, for funds to start a business.

The chairwoman of the Fed, Janet Yellen, is at the leading edge of the Boomer generation born just after WW2. No doubt she and other members of the FOMC are well aware of the difficulties ZIRP has had on other members of her generation. Because the Boomers have been a third of the population as they grew up, they had a consequential effect on the country’s economy and culture. Their income taxes have funded the socialist policies of the Great Society. They have funded the recovery from the Great Recession. Ten years from now politicians will regretfully announce that, in order to save Social Security, they must means test Social Security benefits to reduce payments to retirees with greater assets. Once again, politicians will tap the Boomers for money to fund the policy mistakes that politicians have made for the past few decades.

//////////////////////////

Portfolio Mix

Each year Warren Buffett writes a letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway, the holding company led by Buffett. His 2013 letter made news when Buffett recommended that, after this death, his wife should invest their personal savings in a simple manner: 90% in a low-cost SP500 fund, and 10% in a short term bond fund, an aggressive mix usually thought more appropriate for younger investors. Earlier this year, a reader of CNN Money asked if that would be a practical idea for an older investor approaching or in retirement.

After running several Monte Carlo simulations, the advice was NO, but the reason here is interesting. The 90-10 mix does quite well but has a lot of volatility, more than many older investors can stomach. An investor in their late 40s or early 50s who is making some good money might relish a market downturn. Could be twenty years to retirement so buy, buy, buy while stocks are on sale. If they go down more, buy more.

The sentiment might be entirely different if the investor is ten years older. Preservation of principle becomes more of a concern. Why is this? Let’s look at a sixty year old woman who plans on working till she is seventy so that she can collect a much bigger Social Security (SS) check. During her retirement years she will have to sell some of the equities she has in a retirement fund or taxable account to supplement her SS check. However, the majority of those sales won’t take place for 15 – 20 years. Why then is she more concerned about a market downturn than she might have been at 50 years old? Do we simply feel more fragile at 60 than we do at 50? I suppose it’s different for each person but, in the aggregate, older investors are more cautious even if the probability math says they don’t have to be as careful.

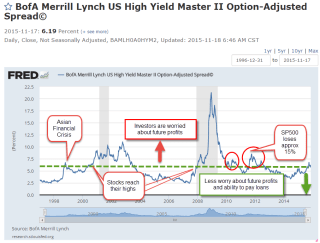

With two weeks to go before the election, the stock market has lost some of its spring/summer fire. Looking back 18 months, the market has had little direction and is now about the same price it was in January 2015. Companies in the SP500 have reported five consecutive quarters of losses, and the analytics firm Fact Set estimates that there will be a small loss in this third quarter of the year, making six losses. Energy companies have been responsible for the bulk of these losses, so there has not been a strong reaction to the losses in the index as a whole.

BND, a Vanguard ETF that tracks a broad composite of bonds, is just slightly below a summer peak that mimicked peaks set in the summer of 2012 and again in January 2015. However, this composite has traded within a small percentage range for the past two years. In fact, the same price peaks near $84 were reached in 2011 and 2012. Once the price hits that point, buyers lose some of their enthusiasm and the price begins to decline. Most of us may think that bonds are rather safe, a steadying factor in our portfolio. Few people are alive that remember the last bear market in bonds because this current bull market is about thirty years old.

Oil has been gaining strength this year. An ETF of long-dated oil contracts, USL, is up about 15% this year. Because it has a longer time frame, it mitigates the effects of contango, a situation where the future price of a commodity like oil is less than the current price. As the ETF rolls over the monthly contracts, there is a steady drip-drip-drip loss of money. Short term ETFs like USO suffer from this problem. Of course, long term bets on the direction of oil prices have been big losers. In 2009, USL sold for about $85. Today it sells at about $20. Here is a monthly chart from FINVIZ, a site with an abundance of fundamental information on stocks, as well as charting and screening tools. The site gives away a lot of information for free and there is a premium version for those who want it.

These periods of low volatility may entice investors into taking more chances than they are comfortable with so each of us should re-assess our tolerance for volatility. In early 2015 there was a 10% correction in the market over two months. How did we feel then? The last big drop was almost 20% in the summer of 2011, more than five years ago. The really big one was more than eight years ago and memories of those times may have dimmed. If you do have easy access to some of your old statements, a quick look might be enough to remind you of those bad old days when it seemed like years of savings just melted away from one monthly statement to the next.

Yes, we are due for a correction but we can never be really sure what will trigger it and these things don’t run on schedule. On a final, dark note – price corrections are like our next illness. We know it’s coming. We just don’t know when.