September 8th, 2013

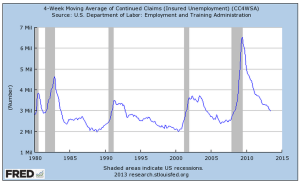

On Thursday, the payroll firm ADP released their estimate of monthly growth of private payrolls, showing a net job gain of 178,000. The weekly report of new unemployment claims was also a positive, a steady decline that indicated that the labor market is healing – but slowly. On Wednesday, the National Federation of Independent Businesses issued their monthly survey of small businesses. For the fourth month in a row employment growth has been negative. Slowing layoffs have contributed to the decline in unemployment claims, but new hiring has also slowed. What to make of that? The market paused on Thursday in advance of Friday’s release of the BLS employment report. Caution mixed with confidence – sounds like a weather report. But there was hope that BLS job gains might approach the 200,000 mark.

The BLS composite picture of employment in August was a both a jaw dropper and a head scratcher, two actions which are difficult to do at the same time. The headline number of 169,000 net job gains was disappointing, but the revisions to July’s job gains was a huge slash – from 162,000 as reported last month to a meager 104,000. About a 150,000 net job gains are needed each month to keep up with population growth.

In a tumultuous job market when the flows of people within the labor market are undergoing a lot of change, downward revisions of this size are understandable. In a supposedly stabilizing labor market, such revisions hint at an underlying fragility.

Is this large downward revision typical of the summer months? In September 2012 the BLS reported upward revisions of over 80,000 jobs for June and July. This year, revisions are down almost that amount so these wild swings may be typical. Businesses may neglect to return the BLS survey on time because they are down at the lake 🙂 In perspective, a revision of 70 – 80,000 jobs is an insignificant percentage of the total working force of over 136 million. But there is no doubt that it affects the mood of investors.

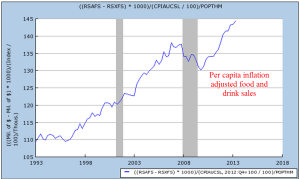

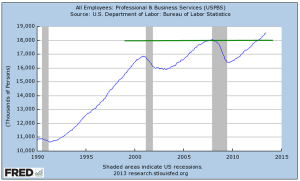

Once again, the usual industries contributed the most to employment gains: professional and business services, retail and drinking establishments and health care workers. I’ll look at some disturbing long term patterns later on in this blog post.

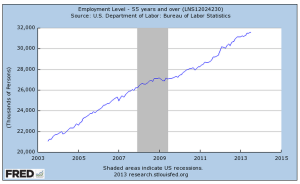

The unemployment rate dropped 1/10th percent to 7.3% but the decline is more a matter of attrition than strength in the labor market. Retirees and others continue to leave the labor force.

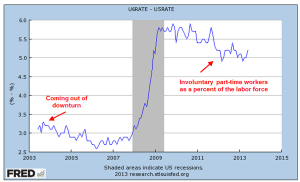

A bright note in this month’s report is the decline in the number of involuntary part-timers, those people who are working part time but want and can’t find a full time job.

The core work force aged 25 – 54 shows little improvement.

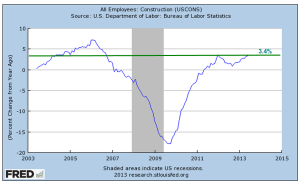

Gains in construction employment have moderated recently.

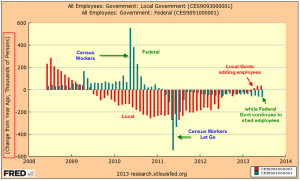

Government employment at the local level is providing a slight boost to the employment gains. Yearly changes in Federal employment continue to show a decline.

As the economy increasingly focuses on services, employees in those industries have become a greater percent of total workers.

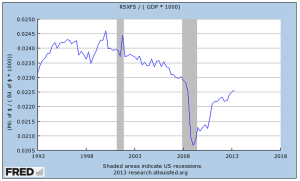

Let’s take a look at the labor mix, or the percent of some occupations of workers to the total work force. During the past thirty years, the ratio of management and professional workers has increased by approximately a third.

In the early decades of the 20th century, agricultural workers made up about 45% of the work force. In the first decades of the 21st century, they have declined to less than 2% of the work force.

A decline in manufacturing and construction has caused a gear shift in the components of the labor force. Service occupations as a percent of the work force have risen steadily.

The conventional narrative says that this has been a natural long term shift from manufacturing to service. But a longer term perspective calls that into question and shows that we are returning and surpassing – this is not new – to a more service oriented labor force.

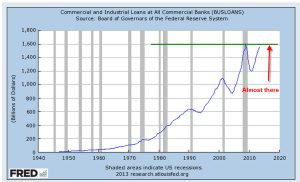

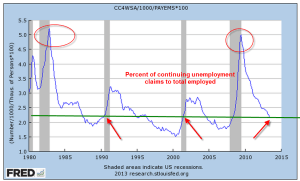

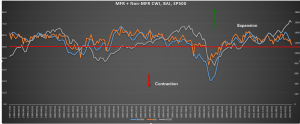

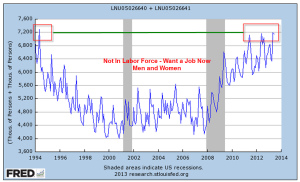

The BLS does not have data before 1983 for this composite of service occupations but the trend indicates that the labor market is much healthier when service occupations are less than about 16.5% of total workers. I’ll call this the Service Occupation Ratio, or SOR. Let’s now look at this thirty year trend and add the unemployment rate.

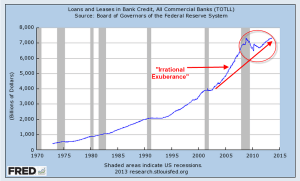

Until the housing bubble of the early 2000s, the unemployment rate followed increases and declines in the SOR. Largely fed by robust employment related to housing, the unemployment rate parted company with the trend line of the SOR. As the recession sparked large job losses, the unemployment rate snapped back into trend with the SOR. Since the recovery, declines in the unemployment rate have not been accompanied by a decline in the SOR.

The trend patterns are even more closely aligned when we look at the wider unemployment rate that includes those who want full time work but can’t find it and discouraged job seekers – or the U-6 rate.

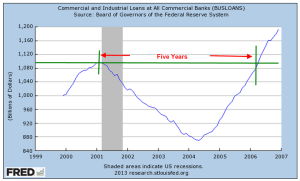

How long will this imbalance last? In the early 2000s, the imbalance lasted about five years. This current imbalance is about three years old, meaning that we may have a few years before the unemployment rate returns to the SOR trend line. What is particularly worrisome is the degree of imbalance. As the unemployment rate drops further away from the SOR trend line, as it did in the early 2000s, it signifies greater tension between these two labor “plates.” Like the movement of land mass tectonic plates, the greater the tension, the more severe the “snap back” to trend. We see the same pattern developing in these past few years. A lower participation rate and more people working part time out of necessity have contributed to a decline in the unemployment rate but the SOR has plateaued.

History is a river; history repeats itself; pick your aphorism. An old Chinese maxim says that a man never crosses the same river twice. History does not repeat itself exactly so that it is unlikely that the current anomaly will resolve itself in the same way as it did in 2008. We can hope that the SOR starts to decline, indicating a healthier labor market. These anomalies can take years to develop but we may find that the correction is as abrupt as 2008.

Each month starts off with a wealth of data. Next week I’ll cover industrial production, retail sales and an update of the CWI composite of manufacturing and non-manufacturing data that I have been charting the past few months.